Grantee Research Project Results

Final Report: On-Chip PCR, Nanoparticles, and Virulence/Marker Genes for Simultaneous Detection of 20 Waterborne Pathogens and Potential Indicator Organisms

EPA Grant Number: R833010Title: On-Chip PCR, Nanoparticles, and Virulence/Marker Genes for Simultaneous Detection of 20 Waterborne Pathogens and Potential Indicator Organisms

Investigators: Hashsham, Syed , Tiedje, James M. , Tarabara, Volodymyr

Institution: Michigan State University

EPA Project Officer: Page, Angela

Project Period: September 1, 2006 through August 31, 2009 (Extended to August 31, 2011)

Project Amount: $600,000

RFA: Development and Evaluation of Innovative Approaches for the Quantitative Assessment of Pathogens in Drinking Water (2005) RFA Text | Recipients Lists

Research Category: Drinking Water , Water

Objective:

The specific objectives of this STAR grant were to i) develop and validate a highly parallel, sensitive, specific, and quantitative biochips for simultaneous detection of waterborne pathogens, ii) develop a nanoparticle-based method for viable but nonculturable cells (VBNCs), iii) develop an efficient sample concentration scheme for fast and efficient recovery of waterborne pathogens.

Summary/Accomplishments (Outputs/Outcomes):

Figure 1. A polyester microfulidic chip fabricated with 64-wells.

| Pathoget | Gene target(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Cryptosporidium parvum | GP60 | 60 kDa glycoprotein |

| hsp70 | 70 kDa het shock protein | |

| Glardia Intestinalis | ß-giardin | concerved protein |

| Leginella pneumophila | dotA | Integral cytoplasmic membrane protein |

| lepB | effector protein | |

| Vitrio cholarae | ctxA | cholera toxin |

| tcpA | toxin-coregulated pilus protein | |

| toxR | two-component regulator | |

| Sigella flexneri | ipaH | invasion plasmid antigen H |

| Campylobacter jejuni | 0414 | putative oxido reductase subunit |

| cdtA | cytoletheal distending toxin A | |

| Echerichia coli 0157:H7 | eaeA | intimin |

| stx1 | Shiga toxin 1 | |

| stx2 | Shiga-toxin 2 | |

| Salmonella enterica | invA | invation protein |

| phoB | phosphate regulon |

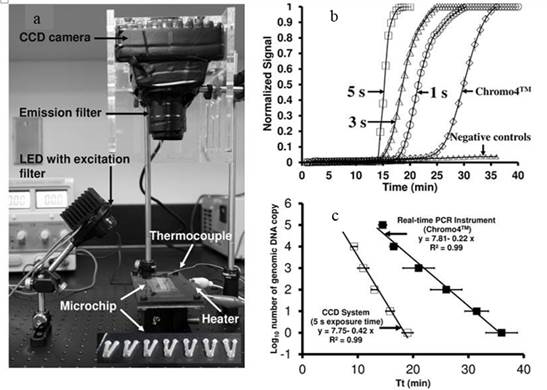

Table 2. (a) Plotograph of the experimental setup consisting of an LED attached with exitation

filter (534 ± 20nm) for illumination, a thin film heater and thermocouple for temperature control,

and a monochromatic CCD camera with emission filter (572 ± 20 nm) for imaging. the inset shows

the microchip with seven V-shaped reaction wells used for RTf-LAMP reactions. This system was

placed in the dark during imaging to avoid any ambient light. (b) Real-time flourescnence LAMP

curves for 105 DNA copies of C. parvum gp60 gene on the microchips (1 s, 3 s, and 5 s CCD exposure

time) and real-time PCR instrument (Chromo4TM), (c) Standard curves for the C. jejuni 0414 gene

amplification on the microchips at 5 s of CCD exposure time and real-time PCR instument. Error bars

represent the standard deviation of the mean from triplicates (Ahmat eta al. 2011)

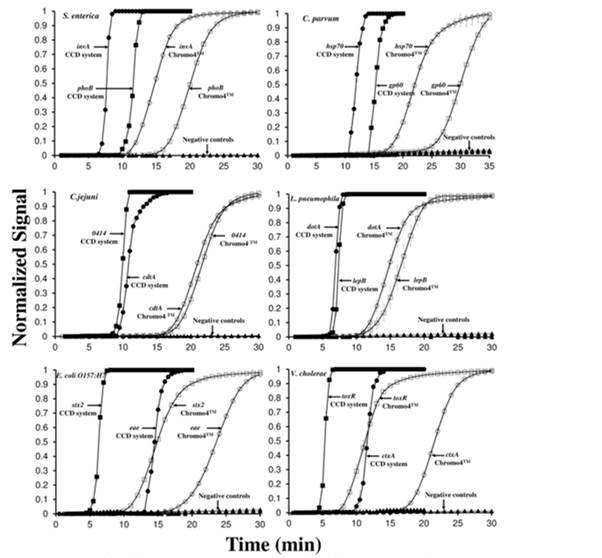

Figure 3. Real-time flourensence LAMP curves of 105 DNA copies of 6 wterborne pathogent

(2 virulent genes for each) on the microchips with 5 s of CCD exposure time (filled circles

and squares) and real-time PCR instument (Chromeo4TM) (open circles and squares). Error

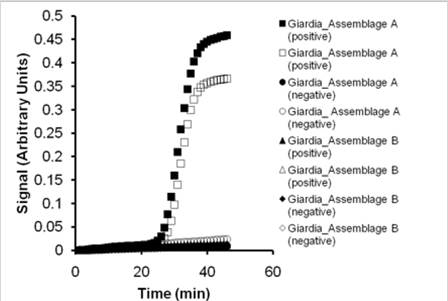

Figure 4. Testing Giardia intestinalis primers for assemblage discriminatino.

The Portland strain (assemplage A) only amplifies with primers designed to

target assemblage A.

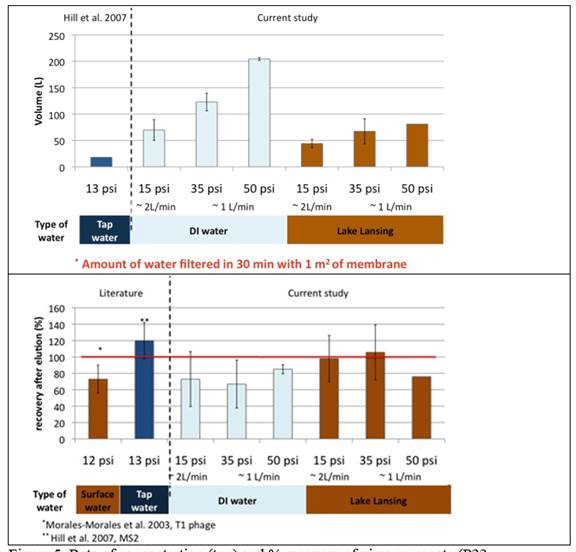

Figure 5. Rate of concentration (top) and % recovery of virus surrogate (P22 bacteriophage) from

deionized and surface water

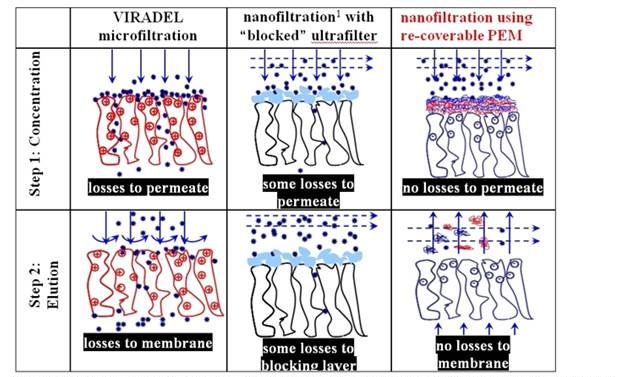

Table 2. Relative benefits of rationally designed, removable polyelectrolyte multilayer (PEM)

1 Note that although ultrafiltration membranes are used in this method, after pre-blocking with

calf serum, the permeate flux decreases to levals typical for nanofiltration membranes.

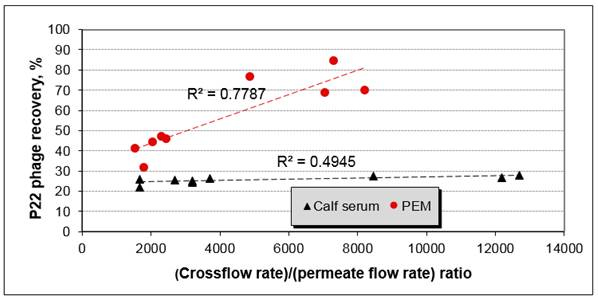

Figure 6. Pre-elution recovery of P22 from deionized water

We further tested the “sacrificial membrane coating” approach in experiments on the recovery of P22 from MBR effluent (MBR plant, Traverse City, MI). The results showed that pre-elution recovery with PEM-coated membrane is significantly (90% confidence interval) higher than with calf-serum blocked membranes (Figure 6). Although post-elution recovery by calf serum-coated membranes was surprisingly high and similar to PEM-coated membranes (~ 80%), the reproducibility of measured recovery values was lower than that for PEM-coated membranes. These results confirmed that we can concentrate and analyze viruses in MBR effluents. We expect that the differences between calf-serum blocked membranes and PEM-coated systems will become even more apparent when working with more adhesive viruses, such as adenoviruses.

Journal Articles on this Report : 3 Displayed | Download in RIS Format

| Other project views: | All 16 publications | 5 publications in selected types | All 3 journal articles |

|---|

| Type | Citation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Ahmad F, Seyrig G, Tourlousse DM, Stedtfeld RD, Tiedje JM, Hashsham SA. A CCD-based fluorescence imaging system for real-time loop-mediated isothermal amplification-based rapid and sensitive detection of waterborne pathogens on microchips. Biomedical Microdevices 2011;13(5):929-937. |

R833010 (Final) EPD10016 (Final) |

Exit |

|

|

Pozhitkov AE, Rule RA, Stedtfeld RD, Hashsham SA, Noble PA. Concentration dependency of nonequilibrium thermal dissociation curves in complex target samples. Journal of Microbiological Methods 2008;74(2-3):82-88. |

R833010 (2008) R833010 (Final) |

Exit Exit Exit |

|

|

Stedtfeld RD, Baushke SW, Tourlousse DM, Miller SM, Stedtfeld TM, Gulari E, Tiedje JM, Hashsham SA. Development and experimental validation of a predictive threshold cycle equation for quantification of virulence and marker genes by high-throughput nanoliter-volume PCR on the OpenArray platform. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2008;74(12):3831-3838. |

R833010 (2008) R833010 (Final) R831628 (2008) |

Exit Exit Exit |

Supplemental Keywords:

Progress and Final Reports:

Original AbstractThe perspectives, information and conclusions conveyed in research project abstracts, progress reports, final reports, journal abstracts and journal publications convey the viewpoints of the principal investigator and may not represent the views and policies of ORD and EPA. Conclusions drawn by the principal investigators have not been reviewed by the Agency.