Grantee Research Project Results

Final Report: Effects of Nanomaterials on Human Blood Coagulation

EPA Grant Number: R832843Title: Effects of Nanomaterials on Human Blood Coagulation

Investigators: Perrotta, Peter L. , Gouma, Pelagia-Irene

Institution: West Virginia University , The State University of New York at Stony Brook

EPA Project Officer: Hahn, Intaek

Project Period: February 1, 2006 through January 31, 2009

Project Amount: $375,000

RFA: Exploratory Research: Nanotechnology Research Grants Investigating Environmental and Human Health Effects of Manufactured Nanomaterials: A Joint Research Solicitation - EPA, NSF, NIOSH (2005) RFA Text | Recipients Lists

Research Category: Nanotechnology , Safer Chemicals

Objective:

Study effects of nanomaterials on the blood coagulation system.

Summary/Accomplishments (Outputs/Outcomes):

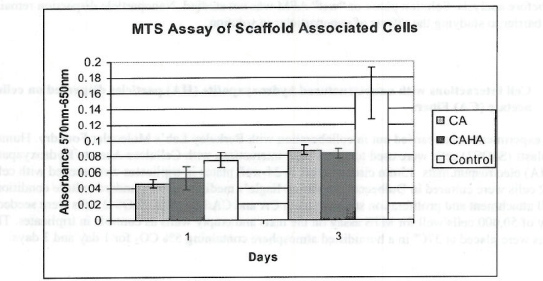

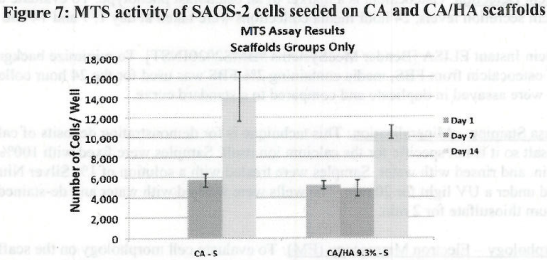

Figure 1. MTS Assay, Absorbance Spectrum after 1 day and 3 days of cells associated with CA and CA/HA mats and Controls. Error bars represent means +- SD

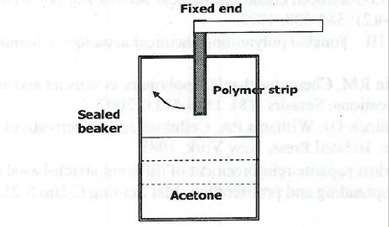

Figure 2. Setup for measuring chemical actuation

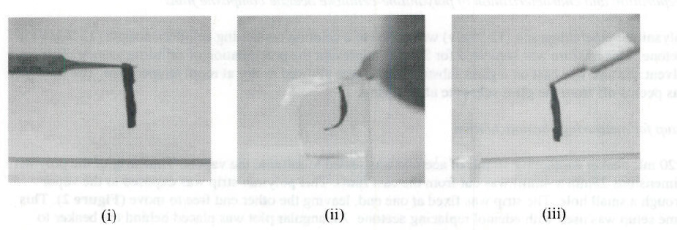

Figure 3. Optical images of bending and recovery in polyaniline-cellulose acetate films (i) Original configureation (ii) Bending in acetome vapors (iii) Recovery in air

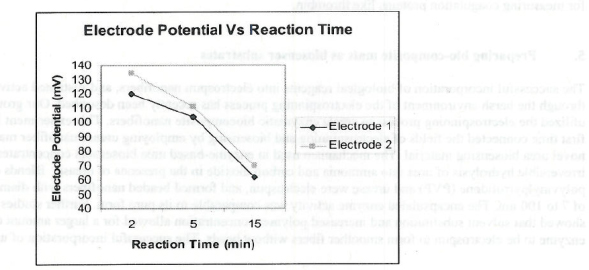

Figure 4. Plot of electrode potential (mV) Va Reaction time (Min). Two sets of readings by two electrodes are shown with similar trends and are in good agreement

| Dose | Thrombin generation (nM/min) | Peak thrombin (nM) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n=17) | NA | 2972 (708) | 195 (45) |

| Ultrafine (n=13) | 0.03 (10) | 3544 (332)* | 244 (24)* |

| Fine (n=8) | 0.03 (10) | 4277 (156)*+ | 273 (13)*+ |

Table 1 Endogeneous thombin potential (ETP) of plasma obtained from rats exposed to

and ultrafine TiO2 as compared to controls. Values denote means (standard deviations).

* Denotes statistically significant differences between the exposed and control group.

+ Denotes statistically significant differences between the exposed groups.

| Dose | N | Thrombin generation (nM/min) |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 15 | 2890 (705) |

| 0.015 (6) | 5 | 3824 (285)* |

| 0.0. (10) | 8 | 4277 (182)* |

| 0.06 (19) | 9 | 3696 (354)* |

| 0.10 (67) | 11 | 3240 (791)* |

| 0.15 (90) | 5 | 3692 (264)* |

Table 2. Endogenous thrombin potential of plasma in rats exposed to various doses of

fine TiO2 particles for 24 hours by inhalation. Values denote means (standard deviations)

* Denotes statistically significant difference between the exposed and control group.

| Particle | Dose | Fibrinogen | vWF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fine | 0.10 (67) | 109,233) | 140 (92) |

| Fine | 0.15(90) | 1,184692 (630, 111)* | 155 (95) |

| Control | NA | 197,544 (30 1, 868) | 105 (58) |

| Ultrafine | 0.015 (6) | 139,740 (187,621) | 135 (69) |

| Ultrafine | 0.03 (10) | 81,810 (13,951) | 1 85 (130)+ |

| Ultrafine | 0.06 | 99,672 (1 06, 580) | 99 (65) |

| Ultrafine | 0.15 (38) | 52,943 (44,247) | 138 (109) |

Table 3. Fibriogen and vWF of plasma in rats exposed to various doses of fine and ultrafine

Ti02 particles for 24 hours using a Luminex assay. Values denote means (standard deviations)

flourescent units.

* Denotes statistically significant differences between this group and all other exposed groups and contros (p>0.001).

+ Denotes statistically significant differences between this group and control (p<0.01).

| Particle | Dose | Fibrinogen (ug/mL) |

|---|---|---|

| Fine | 0.10 (67) | 20 (12) |

| Fine | 0.15 (90) | 87 (8) |

| Control | NA | 51 (24) |

| Ultrafine | 0.03 (10) | 65 (26) |

| Ultrafine | 0.06 (19) | 68 (27) |

Table 4. Fibrinogen and vWF of plasma in rats exposed to vaiours doses of fine and ultrafine

T0)2 particles for 24 hours using a rat fibrinogen ELISA assay. Values denote means (standard deviations)

| Particle | Dose | Troponin I | Troponin T |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fine | 0.10 (67) | 73,612 (4,150)* | 7.042 (1070)* |

| Fine | 0.15 (90) | 67,793 (3,895) | 5,0.8 (975) |

| Control | NA | 69,495 (2.801) | 61.178 (1704) |

| Ultrafine | 0.15 (6) | 75.026 (5,237)* | 7,059 (404)* |

| Ultrafine | 0.03 (19) | 670,1 (4,4017) | 6,379 (617) |

| Ultrafine | 0.06 (19) | 68,705 (3,446) | 6,467 (350) |

| Ultrafine | 0.15 (38) | 7 1.639 (3,519) | 6.594 (779) |

Table 5. Troponin T and Tropinin I levels in plasma of rats exposed to various doses

of cine and ultrafine Ti02 particles for 24 hours using a LUminex assay. Values denote

mean (standard deviations) flourescent units.

| Sample | Cy2 | Cy3 | Cy5 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Internal Standard | Control | 0.15 |

| 2 | Internal Standard | Control | 0.03 |

| 3 | Internal Standard | Control | 0.1 |

| 4 | Internal Standard | 0.15 | 0.1 |

| 5 | Internal Standard | 0.03 | 0.1 |

| 6 | Internal Standard | 0.03 | 0.15 |

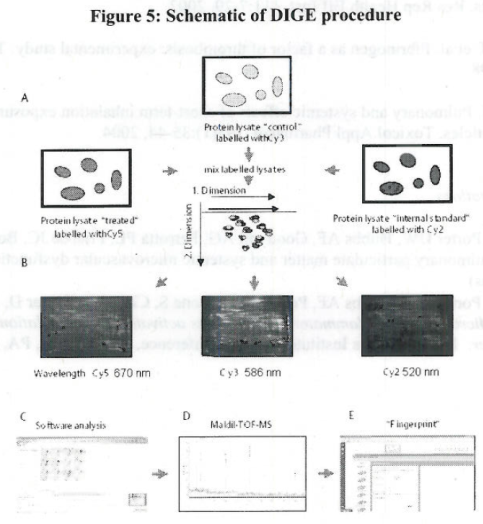

Table 6. Experimental design

Conclusions:

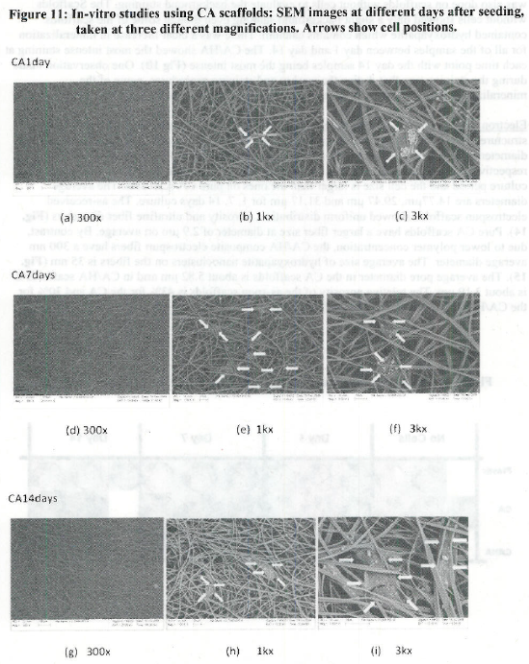

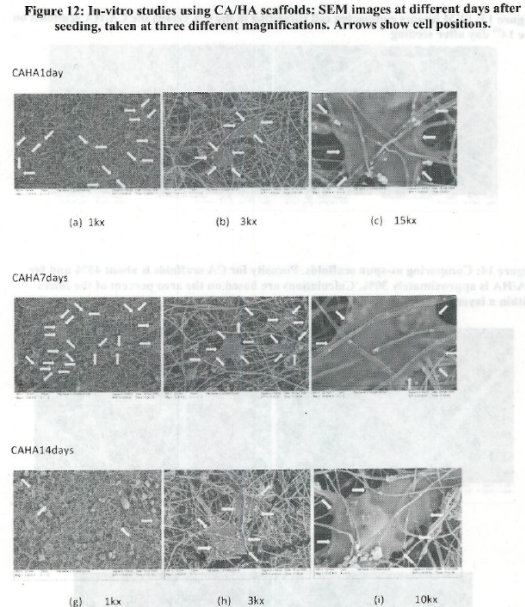

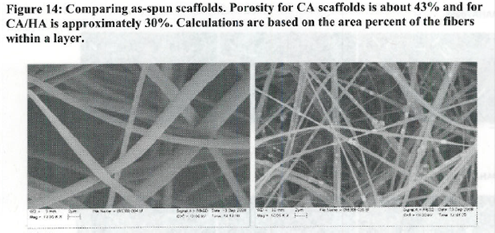

- The use of open nanomanufactured scaffolds (porosity effects)

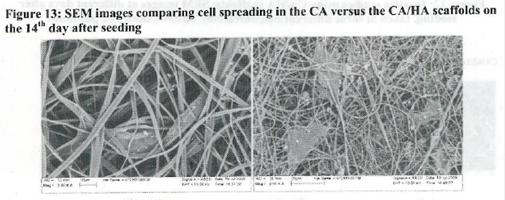

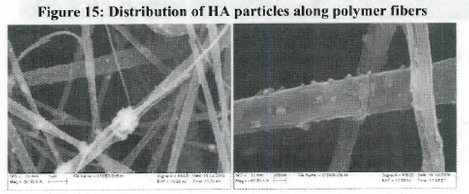

- Relationship between adhesion to nanostructured materials/cues vs cell differentiation

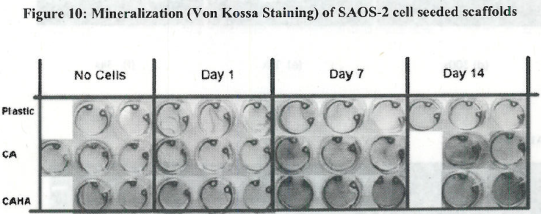

- Observed pattern of mineralization on scaffolds

References:

Journal Articles on this Report : 2 Displayed | Download in RIS Format

| Other project views: | All 22 publications | 5 publications in selected types | All 4 journal articles |

|---|

| Type | Citation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Gadre SY, Gouma PI. Biodoped ceramics: synthesis, properties, and applications. Journal of the American Ceramic Society 2006;89(10):2987-3002. |

R832843 (2007) R832843 (Final) |

Exit |

|

|

Gouma PI, Ramachandran K. Electrospinning for bone tissue engineering. Recent Patents on Nanotechnology 2008;2(1):1-7. |

R832843 (2007) R832843 (Final) |

Exit |

Supplemental Keywords:

Nanotoxicology, coagulation, proteins, thrombosis, nanomaterials, biosensors, biocomposites, thrombin;, Health, Scientific Discipline, ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT, Health Risk Assessment, Risk Assessments, Environmental Microbiology, Biochemistry, Risk Assessment, bioavailability, nanomaterials, nanotechnology, nanoparticle toxicity, blood coagulation enzymes, exposure assessment, blood clottingRelevant Websites:

Stony Brook University: Material Science and Engineering Exit

Progress and Final Reports:

Original AbstractThe perspectives, information and conclusions conveyed in research project abstracts, progress reports, final reports, journal abstracts and journal publications convey the viewpoints of the principal investigator and may not represent the views and policies of ORD and EPA. Conclusions drawn by the principal investigators have not been reviewed by the Agency.