Grantee Research Project Results

Final Report: Tribal Environmental Public Health Indicators

EPA Grant Number: R834791Title: Tribal Environmental Public Health Indicators

Investigators: Donatuto, Jamie , Campbell, Larry

Institution: Swinomish Indian Tribal Community

EPA Project Officer: Hahn, Intaek

Project Period: July 1, 2011 through June 30, 2013 (Extended to June 30, 2014)

Project Amount: $235,517

RFA: Exploring Linkages Between Health Outcomes and Environmental Hazards, Exposures, and Interventions for Public Health Tracking and Risk Management (2009) RFA Text | Recipients Lists

Research Category: Human Health

Objective:

The overarching goals of the project are to create and test environmental public health indicators (EPHIs) specific to Native American tribal communities in the Puget Sound/Salish Sea region of the Pacific Northwest. The hypothesis being tested is that the public health of Native American communities is more accurately evaluated when the health indicators employed reflect Native American definitions of health. The objectives of the research are to: (1) establish a set of environmental public health indicators for Coast Salish communities in the Puget Sound region that reflect the communities’ meanings and prioritizations of health; (2) test the tribal-specific indicator set by employing it to assess the health status of the tribal communities; and (3) evaluate the efficacy of the tribal-specific indicator set by reviewing the health status results with tribes.

Summary/Accomplishments (Outputs/Outcomes):

Introduction

Indigenous communities, including American Indian and Native Alaska communities (as well as other Indigenous communities throughout the world), typically consider mental, social and cultural aspects of community health equally important as, and integrally connected to, individual physiological health (c.f, Arquette et al. 2002, Harris and Harper 1997). For these communities, the issue of how health is defined and assessed in policies and regulations is a high priority because of the considerable environmental public health risks they face from the contamination of their territories and natural resources. Yet current health assessments focus on an overly narrow conceptualization of “health”—one that too strongly emphasizes physiological and disease-based measures, while omitting the less “tangible” aspects, such as cultural health (Arquette et al. 2002, Donatuto, Satterfield and Gregory 2011, Wolfley 1998). This project builds on initial work defining health and wellbeing for the Swinomish Tribe (Donatuto, Satterfield and Gregory 2011), expanding the indicator set to be more representative of multiple Coast Salish Tribes’ meaning and prioritizations of health and wellbeing, and creating and testing methods to assess health status in each community.

Project activities relating to goals and objectives (outputs/ outcomes)

The two main outputs expected of this project were: (1) a set of tribal environmental public health indicators for Coast Salish communities in the Puget Sound region that reflect the communities’ meanings and prioritizations of health (Objective 1); and (2) a current assessment of the environmental public health status of the Puget Sound area tribes (Objectives 2 & 3). Expected outcomes were increased awareness of the need for tribal-specific EPHIs and continued work toward that outcome.

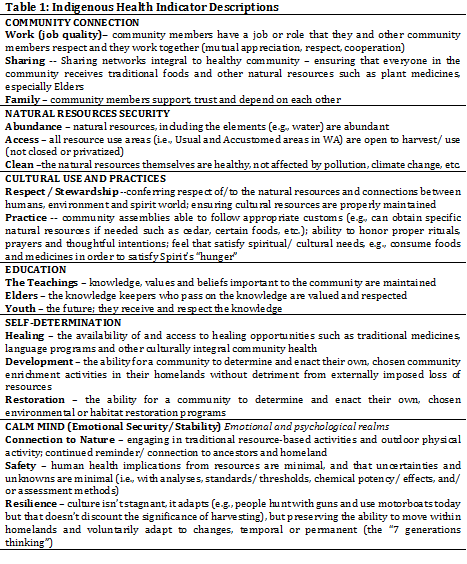

All project goals and objectives were met. Swinomish personnel achieved the project objectives through partnerships established with four other Coast Salish Tribes—the Lower Elwha Klallam, the Port Gamble S’Klallam, the Suquamish, and the Stillaguamish. Project researchers established six key health indicators, each with 3 components (Table 1; Donatuto, Gregory and Campbell, submitted for publication). Researchers named the health indicators “Indigenous Health Indicators” (IHIs) in order to specifically refer to and identify the indicators for future use and in publications. It was agreed that the name “Indigenous Health Indicators” effectively described the tribal environmental public health indicators, yet substantially shortened the name and also broadened the potential use by other resource and land-based groups (e.g., First Nations, Metis, Inuit). The IHIs were pilot-tested in each Coast Salish community who participated in the project, obtaining a snapshot of the current environmental public health status in each of the Tribes. Tribal Councils of each community reviewed the results and approved them for use in the project reports. Results are described in the next section.

Project researchers have presented at conferences, participated in webinars, authored papers, established a website (http://www.swinomish-nsn.gov/ihi/), and had countless discussions about the need for and significance of establishing a set of environmental public health indicators specific to Indigenous communities. Interest in the work is strong and growing, including initiating multiple followup projects, thus demonstrating that the anticipated project outcome of increased awareness has been achieved.

Results:

The six IHIs in their current iteration are: Resources Security, Community Connection, Ceremonial Use, Education, Self Determination, and Calm Mind (Emotional Security). See Table 1 for explanations of the meanings of the indicators (Donatuto, Gregory and Campbell, submitted for publication).

Project researchers established three criteria prior to pilot-testing the indicators in community workshops in order to help gauge the success of the approach. Results will be discussed using the three criteria below:

1. Do the rankings/weightings make sense to participants in terms of expressing accurately the most important aspects of health and wellbeing in their respective community?

2. Are there distinctions among participants in terms of how the indicators are ranked during the workshops?

3. Are there distinctions between the two hypothetical scenarios in each workshop?

Participants had the option to abstain from any of the ranking exercises if they so chose. Yet the overwhelming majority of participants answered every question. Participants answered an average of 96% of the questions. Based on participants’ willingness to complete the questions, the engaged conversations during the workshops and the positive feedback received after the workshops, we conclude that the rankings made sense to participants in terms of expressing accurately the most important aspects of health and wellbeing in their respective community (the first criterion).

In addition, some participants commented that such workshops are a potential avenue for community education and increased involvement by youth. One Suquamish Tribal member said, “It’s a start to communicate to teach our young people to learn.” The use of the wireless polling clickers for voting helped people to feel at ease and also facilitated discussion since the answers appeared on the screen immediately after the polling for each question closed. Many participants, young and old, commented on the ease and fun of using the clickers. Also, the clickers provided anonymity for participants who would not otherwise feel comfortable voicing their opinions in a room of fellow community members.

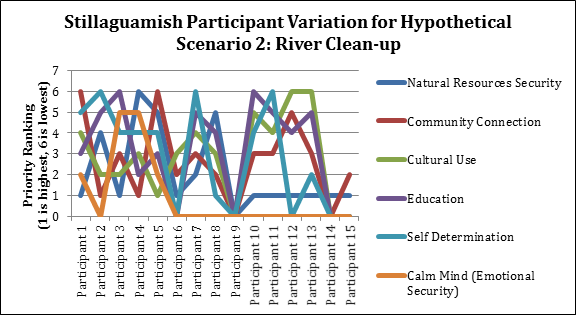

Figure 1 demonstrates that the second criterion was met: that there are distinctions among participants in terms of how the indicators are ranked during the workshops. Figure 1 illustrates how each of the 15 participants in the Stillaguamish workshop ranked the IHIs in the hypothetical scenario of a river clean-up. The highest priority was given a “1,” the second highest a “2,” and so on. Some participants ranked all six indicators, others did not (the “0” ranking marks where an indicator was not ranked).

Figure 1: Participant variation in ranking indicators

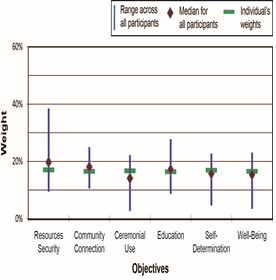

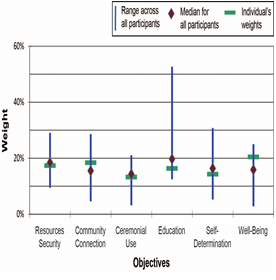

The third criterion-- demonstrating distinctions between the two hypothetical scenarios in each workshop—is illustrated in Figure 2. Figure 2 shows results across Swinomish participants for the two hypothetical scenarios presented at the workshop. The first scenario is about a beach clean up after an oil spill. The second scenario is about a contamination event in a local river. The two summary results depicted below demonstrate the scenario-specific range of weights across all participants for the six IHI indicators along with the median values (depicted by the diamond shapes) and the weights assigned by one (anonymous) individual. For the first scenario, several indicators, such as natural resources security, varied substantially across participants in terms of assigned importance; participants assessed other indicators, such as community connections, more similarly. For the second scenario, the fourth indicator—education—varied considerably in how it was valued by participants relative to the other indicators: on average it was rated slightly higher than any other indicator but the range of responses is high. There was substantial agreement, on the other hand, with respect to the relative importance placed on ceremonial uses of resources and concerns related to resources security. Comparing the relative weights in the two graphs in Figure 2, there are distinctions between the two scenarios.

Figure 2: Ranking and weighting results of two hypothetical scenarios presented at the Swinomish workshop.

Conclusions:

Discussion:

Each Tribe’s workshop results were presented to their respective Council for review. The verbal presentations provided each Council a summary of the results as well as some potential uses for the IHIs: establishing baseline health status, emergency preparedness plans, setting cleanup guidelines, and a host of other health-related policies, both on and off Reservation, with the caveat that the indicator set is still in the testing phase. The feedback to date from each of the Councils has been positive and supportive, with ongoing discussions about how the IHIs could be furthered refined and incorporated into decision-making practices and policies.

Because the results are illustrative and serve only as a test of the IHIs themselves and evaluation the methods, project researchers underscore that these data should not be used as evidence of generalized relationships among the indicators. These data are not representative of the environmental public health status or beliefs of any of the Tribes involved in the project. However, based on the pilot-test results, it is clear the indicators are able to distinguish both between hypothetical scenarios and among the six different measures of value. An identical result for the two scenarios would not demonstrate sufficient sensitivity in the measures. An assumption of equality among the IHIs—the default option if explicit weightings were not conducted—would not present an accurate picture of the views of community members.

Other positive outcomes found during the pilot-testing was that the descriptive ranking system used was able to protect proprietary knowledge (e.g., specific traditional stories, harvest locations, ceremonial practices) while still conveying the importance of the health indicators for community members. The workshops provided the opportunity for community members to actively engage in discussing what matters most to them, with the comfort level of knowing that any proprietary data would remain “hidden” behind the simple constructed scales used in the ranking exercises. These constructed scales (e.g., a narrative scale of “very good” to “very bad” or a Likert scale of 1-4) were easy to understand and interpret for both community members and outside people alike.

The workshops employed wireless polling clickers to collect community members ranking answers. The overwhelming response from participants was that the clickers were easy to use and “fun.” Because a summary of responses to a question was immediately projected onto the screen after each vote, the answers spurred discussion and story telling that provided more depth to the answers. For example in the Lower Elwha workshop, participants tended to be optimistic about community health in the future. During the discussion, several people talked about the success of the recent dam removals on the Elwha River, connecting the massive restoration projects with working toward improving community health.

The wireless polling clickers also allowed more freedom for participants to vote, which may be important when a participant is in a room full of family members, some of whom are elders, and it is not appropriate to voice a contrasting opinion. The clickers collate the data, allowing each person to vote anonymously even in a workshop setting.

The names of the indicators underwent several iterations during the course of the project. For example, the “Calm Mind” indicator was called “Wellbeing” in the first pilot-test workshops, but was later changed based on participants feedback and additional research regarding what that indicator meant to reflect. Figure 2 data are from the first workshop held at Swinomish and thus use the “Wellbeing” term. It was decided that “Wellbeing” was too broad a term with several definitions in the literature and could encompass all the indicators by some definitions; a more descriptive name was required. However, it is anticipated that this name may change again in subsequent iterations.

Researchers found the IHIs to be flexible and responsive enough to be tailored to each individual community’s definitions of health. For example, the Cultural Use indicator was named differently depending on the vernacular of the community. Even neighboring Tribes use different terms to express similar materials or activities. The Port Gamble S’Klallam representative suggested using the term “Spiritual/ Cultural Use;” the Lower Elwha representative preferred the term, “Ceremonial Use,” and the Suquamish representative suggested the term “Cultural Use and Practices.” Another example is what is included in the IHIs terms themselves, such as “Natural Resources Security”—Suquamish participants decided that water, soil and air, in addition to plant and animal species and habitats, are necessary to include.

Going forward, the project team has identified the weighting portion of the methods as requiring refinement and additional testing. Several participants in each workshop verbally commented that it was difficult for them to understand the swing-weighting concept; this response suggests that other weighting methods such as paired comparisons also should be tested. Other participants noted that ranking and weighting important concerns is a cognitively and emotionally challenging task, yet understood the reasons why it may be necessary (in short: if ranking and weighting are not done, then by default all 18 measures across the 6 different indicators are assumed to have equal importance). Overall, participants were supportive and understood that the results could help communities to generate and select among alternative projects or cleanup actions. There was general agreement among participants that not all the indicators were equally important in terms of helping to identify the key potential effects of a specific proposed resource development initiative or cleanup plan; instead, it was clear from the scenarios exercise that the type and context of a proposed initiative (what type of actions might take place, what types of resources might be affected, what parties would be in charge) made a difference.

Based on the workshop findings, the IHIs have potential to be a technically effective methodological tool for recognizing and equitably incorporating Indigenous definitions and prioritizations of health in to environmental public health assessments. Economically, costs are kept low by working with a community representative to organize the workshops, thus engaging people in the community, minimizing travel costs, and minimizing costs of data collection of a representative sample of community members by employing a workshop setting. Using simple descriptive scales allows for findings to be easily assessed along other assessment data. However, incorporating Indigenous Knowledge with other knowledge systems has been problematic historically. Project researchers are therefore cautious with respect to the proposed IHI framework. Taken out of context, Indigenous Knowledge can be misrepresented, misunderstood, or both. By making use of constructed scales to describe some of the key nonphysical, community-based environmental indicators of Indigenous health, the long-term goal is to provide an equal playing field for learning more, from both Indigenous and non-Indigenous perspectives, about how past, present and future changes to the natural resource base can affect Indigenous health and to elucidate the many complex relationships between humans and the environment upon which human health is dependent.

The researchers will continue to test and refine the IHIs with Indigenous communities. A recently completed climate change-related project pilot-tested the usefulness of the IHIs in relation to sea level rise and storm surge impacts on beaches in Washington State and British Columbia (a North Pacific Landscape Conservation Cooperative and the NW Climate Science Center grant award to the Swinomish Tribe #F12AP0094). A project to pilot test Indigenous community health indicators on a national scale with four diverse Tribes across the United States was recently initiated (National Institutes of Health # 1R24LM011809-01). Most recently, the Swinomish Tribe received funding to implement the IHIs in assessing climate change-related impacts to first foods, habitats and culturally important shoreline areas on the Swinomish Reservation for incorporation into the Swinomish Climate Action Initiative (EPA STAR #RD83559501).

References:

Arquette M, Cole M, Cook K et al. Holistic risk-based environmental decision making: A Native perspective. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2002; 11:259–164.

Donatuto J, Satterfield T, Gregory R. Poisoning the body to nourish the soul: Prioritising health risks and impacts in a Native American community. Health, Risk and Society, 2011; 13:103–27.

Harris S, Harper B. A Native American exposure scenario. Risk Analysis, 1997; 17 (6):789–95.

Wolfley J. Ecological risk assessment and management: Their failure to value indigenous traditional ecological knowledge and protect tribal homelands. American Indian Culture and Research Journal, 1998; 22:151–69.

Journal Articles on this Report : 3 Displayed | Download in RIS Format

| Other project views: | All 3 publications | 3 publications in selected types | All 3 journal articles |

|---|

| Type | Citation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Donatuto J, Grossman EE, Konovsky J, Grossman S, Campbell LW. Indigenous community health and climate change: integrating biophysical and social science indicators. Coastal Management 2014;42(4):355-372. |

R834791 (2013) R834791 (Final) |

Exit Exit |

|

|

Donatuto J, Campbell L, Gregory R. Developing responsive indicators of indigenous community health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2016;13(9):E899 (16 pp.). |

R834791 (Final) R835595 (2016) |

Exit Exit Exit |

|

|

McOliver CA, Camper AK, Doyle JT, Eggers MJ, Ford TE, Lila MA, Berner J, Campbell L, Donatuto J. Community-based research as a mechanism to reduce environmental health disparities in American Indian and Alaska Native communities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2015;12(4):4076-4100. |

R834791 (Final) R833706 (Final) R833707 (Final) |

Exit Exit |

Supplemental Keywords:

Risk assessment, risk management, seafood, fish consumptionRelevant Websites:

http://www.swinomish-nsn.gov/ihi/

Progress and Final Reports:

Original AbstractThe perspectives, information and conclusions conveyed in research project abstracts, progress reports, final reports, journal abstracts and journal publications convey the viewpoints of the principal investigator and may not represent the views and policies of ORD and EPA. Conclusions drawn by the principal investigators have not been reviewed by the Agency.