Grantee Research Project Results

2009 Progress Report: Elevated Temperature and Land Use Flood Frequency Alteration Effects on Rates of Invasive and Native Species Interactions in Freshwater Floodplain Wetlands

EPA Grant Number: R833837Title: Elevated Temperature and Land Use Flood Frequency Alteration Effects on Rates of Invasive and Native Species Interactions in Freshwater Floodplain Wetlands

Investigators: Richardson, Curtis J. , Qian, Song S. , Flanagan, Neal

Current Investigators: Richardson, Curtis J. , Flanagan, Neal , Ho, Mengchi

Institution: Duke University , Nicholas School of the Environment and Earth Sciences

EPA Project Officer: Packard, Benjamin H

Project Period: April 1, 2008 through March 31, 2011 (Extended to March 31, 2012)

Project Period Covered by this Report: April 1, 2009 through March 31,2010

Project Amount: $598,107

RFA: Ecological Impacts from the Interactions of Climate Change, Land Use Change and Invasive Species: A Joint Research Solicitation - EPA, USDA (2007) RFA Text | Recipients Lists

Research Category: Aquatic Ecosystems , Ecological Indicators/Assessment/Restoration , Climate Change

Objective:

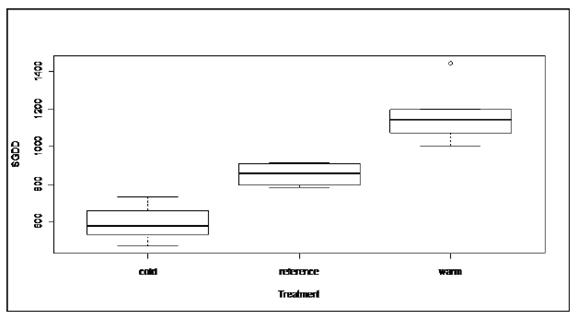

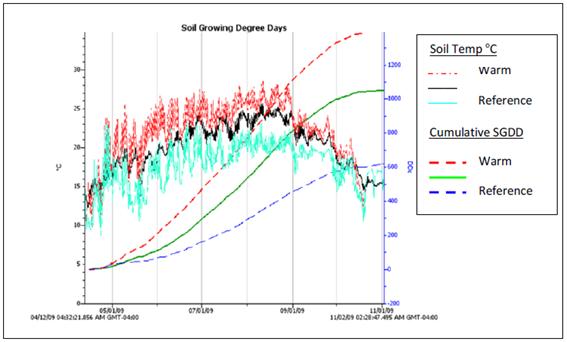

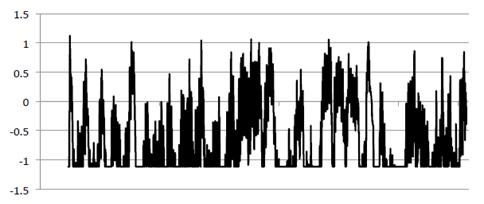

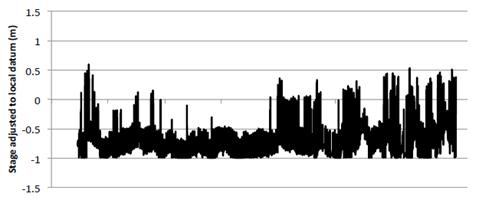

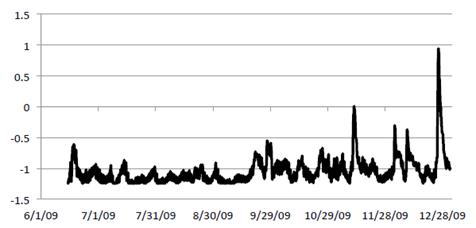

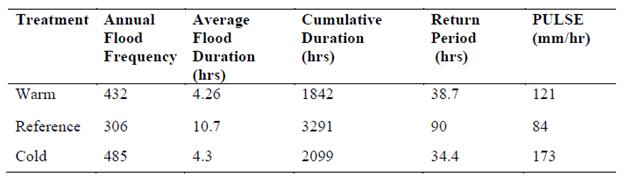

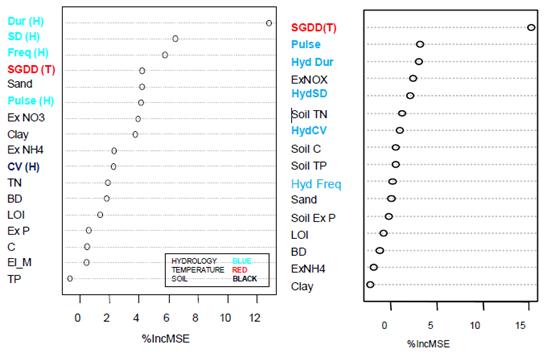

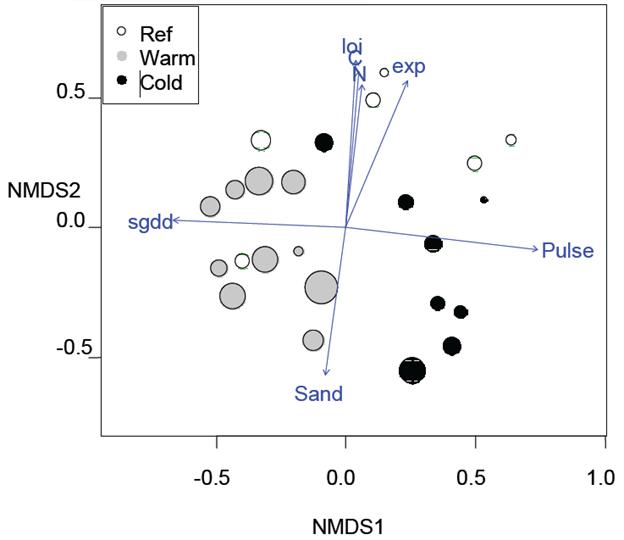

The primary objective is to assess how predicted climate and land use driven changes in hydrologic flux and temperature regimes of floodplain ecosystems affect plant communities in terms of their vulnerability to the establishment and spread of invasive species, and in turn ecosystem functions and services. Future climate scenarios for the southeastern U.S. predict that surface water temperatures will warm (in concert with air temperature) and that stream flows will likely decrease, with a greater proportion of annual watershed hydrologic yield occurring during major storm events. Land use changes (urban vs. forested etc.) have been shown to also raise water temperature and increased pulsed water releases during storms. Specifically, we focus on the relationships between native species composition, diversity, productivity, and invasibility of floodplain ecosystems affected by alterations of water temperature and annual hydrographs driven by climate change and land use change (urban, forested and agricultural). We will use a combination of varying scale experimental studies and one novel large-scale regional study to verify our experimental and threshold modeling results.

Progress Summary:

Future Activities:

Journal Articles:

No journal articles submitted with this report: View all 9 publications for this projectSupplemental Keywords:

wetlands, watershed, land use, climate change, invasive species, temperature shifts, pulsed water, water quality, altered stable states, nonlinear thresholds., RFA, Ecosystem Protection/Environmental Exposure & Risk, Air, Scientific Discipline, Ecological Risk Assessment, Atmosphere, Regional/Scaling, Monitoring/Modeling, Air Pollution Effects, Atmospheric Sciences, Hydrology, climate change, Environmental Monitoring, invasive species, biodiversity, Global Climate Change, ecosystem assessment, climate model, water quality, coastal ecosystem, global change, atmospheric chemistry, ecological models, coastal ecosystems, climate models, environmental measurement, climate variability, habitat preservation, environmental stress, UV radiation, habitat diversity, anthropogenic, meteorology, land use, regional anthropogenic stresses, greenhouse gasesRelevant Websites:

Duke University Wetland Center website www.env.duke.edu/wetland Exit

Progress and Final Reports:

Original AbstractThe perspectives, information and conclusions conveyed in research project abstracts, progress reports, final reports, journal abstracts and journal publications convey the viewpoints of the principal investigator and may not represent the views and policies of ORD and EPA. Conclusions drawn by the principal investigators have not been reviewed by the Agency.