Grantee Research Project Results

2010 Progress Report: Project 4 -- Transport and Fate Particles

EPA Grant Number: R832414C004Subproject: this is subproject number 004 , established and managed by the Center Director under grant R832414

(EPA does not fund or establish subprojects; EPA awards and manages the overall grant for this center).

Center: UC Davis Center for Children's Environmental Health and Disease Prevention

Center Director: Van de Water, Judith

Title: Project 4 -- Transport and Fate Particles

Investigators: Wilson, Dennis , Barakat, Abdul , Louie, Angelique

Current Investigators: Wilson, Dennis , Louie, Angelique

Institution: University of California - Davis

EPA Project Officer: Chung, Serena

Project Period: October 1, 2005 through September 30, 2010 (Extended to September 30, 2011)

Project Period Covered by this Report: October 1, 2008 through September 30,2009

RFA: Particulate Matter Research Centers (2004) RFA Text | Recipients Lists

Research Category: Human Health , Air

Objective:

-

To characterize the time course, tissue distribution, and mechanisms of particulate matter (PM) accumulation in the systemic circulation and target organs.

-

To evaluate the effects of size and surface-fixed charge on this process.

-

To determine how altered lung structure affects systemic particle distribution.

-

To characterize how fluid flow modulates particle interactions with vascular endothelial cells.

Progress Summary:

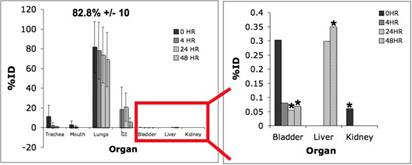

Specific Aim 1: To characterize the time course and distribution of circulating particulates in vivo. In the last year, we have focused on determining the effects of a co-mixture containing labeled (64-Cu) polystyrene particles and PM2.5 (Kent Pinkerton) on lung retention and transport in a normal mouse model. Ambient particles have been shown to cause a physiological response in the lung (increased inflammation, permeability, oxidative stress). We hypothesized that delivering ambient particles could induce these changes in the lung and we could observe differences in transport/retention with our current radiolabeled model of PM (polystyrene). We have focused on two PM2.5 concentrations: 50 µg, and 500 µg doses. The region of interest analysis of the PET images of the 50 µg co-mixture dose is shown below in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Biodistribution of 50 µg co-mixture dose over 48 hours in the normal mouse. Lung retention at 48 hours was 82.8%DD +/- 10 and significant (p<0.05) changes in secondary organ accumulation were shown in the bladder, liver and spleen (*). DD = deposited dose.

|

|

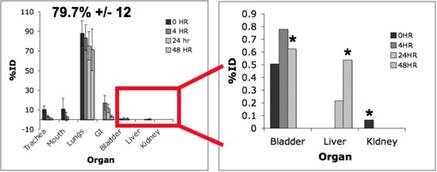

For the 500µg dose similar retention and secondary organ accumulation was observed (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Biodistribution of 500µg dose over 48 hours. Lung retention at 48 hours was 79.7%DD +/- 12 and significant changes (p<0.05) were observed in the bladder, liver and spleen (*).

|

|

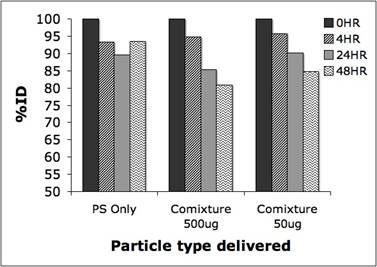

Comparing the lung retention with only labeled particles and both co-mixture doses we observed a decreasing trend over the 48 hour study period (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Lung retention over 48 hours for PS only and co-mixture doses (50µg and 500µg).

|

|

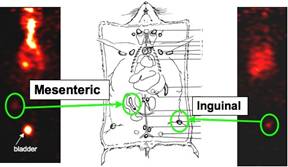

In addition to changes in secondary organ accumulation, we also observed potential lymphatic signal for both co-mixture doses (Figure 4). This potential signal is currently under further investigation.

Figure 4. Potential lymphatic signal after co-mixture delivery. Sites of accumulation are located near the mesenteric and inguinal lymph nodes.

|

|

To verify that the PM2.5 used for these studies is inducing the expected inflammation reported in the literature we looked at histological sections of the lungs for neutrophil content. (Work done by Laurel Plummer-Kent Pinkerton Lab) A dose-response relationship was observed for neutrophil and cellular influx in the lungs. Other work for this year included quantitative analysis of asthma PET data from the previous year and radio-labeling optimization for new models of PM. Future work includes utilizing new model of PM (20nm polystyrene) for both co-mixture and PS only experiments with either PET or SPECT. Also, repeating co-mixture experiment for ex vivo analysis of lymphatic vessels.

Specific aim 3: To evaluate potential mechanisms of PM transport across epithelial and endothelial barriers. Mechanisms of Endothelial and Epithelial transport using synthetic fluorescent and electron dense ultrafine particles. In previously reported work, we characterized the transport of 30 nm synthetic iron oxide particles across endothelial cell monolayers and demonstrated vesicular transport though caveolar like structures by 4 hours. We further characterized this as vesiculocaveolar transport using fluorescence tagged silica particles with confocal microscopy. We now extended this work to ask whether similar rates of transport occur in cultured human airway epithelial cells. We found, in contrast to studies with endothelial cells, airway epithelium did not allow transport during a 4 hour incubation period.

Specific aim 4: To characterize how fluid flow modulates particle interactions with vascular endothelial cells. (Barakat) In vivo, vascular endothelial cells are constantly exposed to flow. Research over the past two decades has demonstrated that fluid flow regulates endothelial cell phenotype. Furthermore, the details of this regulation depend on the type of flow to which the cells are subjected. Endothelial cells exposed to either steady (time-independent) or non-reversing pulsatile flow develop an anti-inflammatory phenotype that is largely protected from atherosclerosis. On the other hand, endothelial cells subjected to oscillatory flow exhibit a pro-inflammatory phenotype and are prone to the development of vascular pathology. Oscillatory flow occurs at arterial branches and bifurcations, and these regions correlate with the development of early atherosclerotic lesions.

We have been investigating how different types of flow modulate PM-induced inflammation in cultures of human aortic endothelial cells (HAECs). The experiments involve pre-shearing HAECs with either steady or oscillatory flow for a period of 24 hrs in order to establish either an anti- or pro-inflammatory cellular phenotype. At the end of the flow period, HAECs are exposed to PM for 4 hrs under static conditions, and the mRNA and protein levels of the three inflammatory markers ICAM-1, IL-8, and MCP-1 are subsequently assessed using real-time PCR, Western blotting, or ELISA. The results are compared to control cells that are not exposed to flow. Our initial experiments focused on laboratory nanoparticles, most notably zinc oxide (ZnO). These particles were selected because we had previously shown that they induce HAEC inflammation under static (no flow) conditions (Gojova et al., Environmental Health Perspectives, 2007). As illustrated in Figure 4.1, HAECs pre-conditioned with oscillatory flow exhibit a higher level of ZnO-induced inflammation, as measured by the mRNA expression levels of the inflammatory markers IL-8, ICAM-1, and MCP-1, than cells not exposed to flow or cells pre-conditioned with steady flow. The same behavior is also observed at the protein level (Figure 4.2). These results, if conformed in vivo, suggest that particle-induced inflammation would be exacerbated considerably in arterial regions susceptible to atherosclerosis (where oscillatory flow occurs) than in atherosclerosis-resistant regions.Figure 4.1: Relative mRNA levels of three inflammatory proteins (A) IL-8, (B) ICAM-1 and (C) MCP-1 in HAECs as determined by real time PCR after ZnO treatment of HAECs grown under static condition or pre-sheared with steady laminar or oscillatory flow for 24h. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. * denotes statistically significant increase (p<0.05) relative to static control (CT) group; # denotes statistically significant increase (p<0.05) relative to static ZnO group.

Figure 4.2: Inflammatory protein levels in HAECs after ZnO treatment. Cells were maintained under static conditions or pre-sheared with either steady or oscillatory flow for 24h. (A) IL-8; (B) MCP-1; (C) ICAM-1. IL-8 and MCP-1 secretion levels were determined by ELISA. ICAM-1 levels were established by Western blotting and were normalized relative to GAPDH which served as an internal control. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. * and ** respectively denote statistically significant difference at p<0.05 or p<0.01 relative to static control (CT) group; # and ## respectively denote statistically significant difference at p<0.05 or p<0.01 relative to static ZnO group.

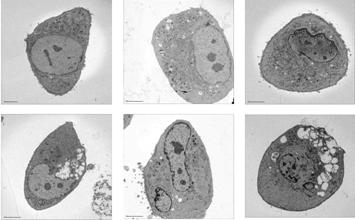

Why HAEC pre-conditioning with oscillatory flow leads to amplification of PM-induced inflammation remains unknown and is a question of critical importance. We have performed some transmission electron microscopy (TEM) experiments that may shed some light on this issue. As illustrated in Figure 4.3, ZnO nanoparticles induce considerable vacuole formation in HAECs that have not been pre-exposed to flow. This vacuolization appears even more pronounced in cells pre-conditioned with oscillatory flow but is largely absent in cells pre-conditioned with steady flow. In previous studies, we had shown that such vacuoles are involved in particle internalization into and transport within the cells. Therefore, it is possible that the results shown in Figure 4.3 reflect enhanced particle internalization in cells pre-conditioned with oscillatory flow and reduced particle uptake in cells pre-conditioned with steady flow.|

|

Figure 4.3: Transmission electron micrographs demonstrating ZnO nanoparticle-induced vacuole formation in HAECs. Note the prominent vacuoles in cells that were either not pre-sheared or pre-sheared with oscillatory flow. These vacuoles are absent in cells pre-sheared with steady flow.

|

|

Although the particles did not lead to cell death, they did affect cell viability in more subtle ways as assessed by the mitochondrial activity-sensitive assay WST-1. As illustrated in Figure 4.5, ambient particles applied for a period of 24 hrs reduced HAEC viability in a dose-dependent fashion. Interestingly, particles from the Fresno Summer 2008 campaign had the most pronounced effect. At the highest concentration tested (6.6 µg/cm2, equivalent to 50 µg/ml), particles from this campaign reduced HAEC viability by ~50%.

We also assessed the effect of the ambient particles on HAEC inflammation. As shown in Figure 4.6, particles elicited cellular inflammation as assessed by mRNA levels of the three inflammatory markers ICAM-1, IL-8, and MCP-1. The inflammatory response was both time- and dose-dependent. Once again, the Fresno Summer 2008 particles had the most pronounced effect.

Figure 4.6: Effect of Fresno (Winter 2009 or Summer 2008 campaigns) and Westside (Winter 2008 campaign) ultrafine particles on HAEC inflammation as assessed by the mRNA levels of ICAM-1, IL-8, and MCP-1.

Particle interactions with cells are affected by the state of the particles as they make contact with the cell surface. Of particular importance in this regard is particle aggregation. In order to understand particle-cell interactions, it is important to establish the extent and dynamics of particle aggregation as well as how aggregation is affected by various parameters including the cell culture media and any proteins present in the media. Furthermore, because we are interested in flow, it is important to establish if flow has an effect on particle aggregation. We have used dynamic light scattering (DLS) to determine the aggregation dynamics of laboratory nanoparticles, most notably iron oxide (Fe2O3) and ZnO particles. Figure 4.7 depicts the DLS results of Fe2O3 and ZnO nanoparticle aggregation in deionized water. Previous studies had established that the primary particle size in both cases is of the order 60-100 nm. Several measures of particle aggregation are shown including the “effective” hydrodynamic diameter (based on the mobility of the aggregates within the measurement volume, a value heavily driven by larger aggregates), the “peak” diameter, and the “number average” diameter. These different measures represent different moments of the measured distributions. The results demonstrate that Fe2O3 particles in water (the “no sonication” bars in Figure 4.7) aggregate considerably. These aggregates are very effectively broken down after sonication for 1 min. Following sonication, the aggregates are slow to re-form. ZnO particles behave in a largely similar way to Fe2O3 particles, but the initial aggregates are significantly smaller.We have performed DLS measurements to assess the effects of media composition as well as the presence of serum in the media on Fe2O3 and ZnO particle aggregation dynamics following probe sonication. The results, depicted in Figure 4.8, demonstrate that particles aggregate to a greater degree in either PBS or cell culture medium (EBM) than in water. Furthermore, the presence of serum generally reduces aggregation. This effect is especially pronounced in water, where virtually no aggregation occurs. We hypothesize that the increased aggregation in PBS and cell culture media relative to water is attributable to differences in ionic strength. We also suspect that the reduction of aggregation by serum incubation is due to the fact that serum coating renders particle surfaces negatively charged, and the electrostatic repulsion limits the extent of aggregation.

Figure 4.8: Dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements of aggregation dynamics following probe sonication for A: Fe2O3 and B: ZnO nanoparticles in different suspension media. Each bar corresponds to a time step of 1 hr. Measured values from three replicates were averaged at each time step. Data are mean ± SEM. PBS: phosphate-buffered saline. EBM: endothelial basal media. Complete: EBM plus all additives used in routine HAEC culture including serum.

The previous experiment does not indicate the time scale for shearing of aggregates. Therefore, we performed a complementary experiment in which effective diameter was measured over the duration of flow (Figure 4.10). The results are approximated well by an exponential decay with a time constant of 1.1 hrs (dashed curve). Based on these results, we believe that the particles used in our cell culture system are probably minimally aggregated for most of the duration of a 6-24 hr flow experiment.

Figure 4.10: Effect of flow on aggregation of iron oxide nanoparticles in complete medium. Evolution of particle diameter over 4 hrs under flow conditions. Also shown are particle diameters under flow conditions at the beginning and end of the 4-hr period. Data are mean ± SEM with n=2.

Mechanisms of ultrafine PM transport across vascular barriers

Our previous work evaluating mechanisms of trans-endothelial transport of synthetic ultrafine particles demonstrated that PM in the nanoparticle range (20-50 nM) is transported across endothelial cell barriers relatively quickly through veiscuol-caveolar transport while larger particles (500 nM) are not. We have expanded these studies to evaluate the effect of size on cellular function using theoretically inert laboratory generated monosized silica. We have evaluated effects on barrier function by electrical conductance measurements (ECIS system Applied Biophysics). Results of these studies, described below, suggested that 20 nM silica particles were toxic in cultured endothelium. This suggests that internalization of PM is important in generating toxicity. We have further investigated the mechanism of nanofine silica toxicity by comparing intracellular ROS generation and assays for apoptosis.

ECIS

20nm and 500nm silica suspended in complete medium was applied to confluent monolayers of Human Pulmonary Microvascular Endothelial cells (HPMVEC) in ECIS chamber plates. The ECIS apparatus measured monolayer resistance (tests the integrity of intracellular junctions) and monolayer impedance (tests the integrity of connections between the basal side of the cell and the growth substrate). As shown in Figure 1, an image generated by the ECIS proprietary software, the ability of the monolayer to maintain resistance was obliterated by the application of 20nm silica at 50µg/ml within 12 hours of treatment application (p < 0.05). The figure also shows that 20nm silica at 10µg/ml has an effect on monolayer resistance but it is not as profound as the 50µg/ml treatment, though it differs significantly from control by 40 hours post treatment (p=0.012). Figure 2 shows the mean for each treatment when the experiment was repeated three times. There was no difference from control with the 500nm particles at either treatment dose.

Figure1:

Figure 2:

The monolayer impedance showed much the same trends. As shown in figure 3, the 20nm silica treatment at 50µg/ml showed the same precipitous decrease in monolayer impedance by 12 hours post-treatment (p<0.05) and the 10µg/ml treatment was significantly different from control at 40 hours post treatment. Figure 4 shows the mean data from three separate experiments. There was no difference from control after treatment with the 500nm silica particles at either dose.

Figure 3:

Figure 4:

Overall, the ECIS experiments show that there is a significant difference in the endothelial response to silica treatment that is based on particle size and both the intracellular junctions and cell-substrate junctions are affected.

Reactive Oxygen Species Generation Human Pulmonary Artery Endothelial Cells (HPAEC) exposed to 20nm and 500nm silica show an increase in ROS generation as measured with 5-(and-6)-carboxy-2',7'-dichlorofluorescein dictate (carboxy-DCFDA) dye (Molecular Probes) which passively diffuses into cells and is then cleaved by esterases active in the production of ROS. Figure 5 shows the number of pixels positive for intracellular ROS generation 3 and 24 hours after silica treatment. 0.25µM PMA was used as a positive control. 20nm silica at 50µg/ml shows a significant difference from PMA control at 3 hours (p=0.004) and 24 hours (p=0.023). At 24 hours, there is significant difference between 20nm silica 10µg/ml dose and the PMA control (p=0.0056). By 24 hours, there is very little ROS detection in the 20nm 50µg/ml treatment, leading to the conclusion that many of the cells have died at by this time point. At 24 hours, the 500nm silica at both 10µg/ml and 50µg/ml doses are not different from the PMA control, showing that ROS are generated after 500nm silica exposure, but more slowly than with the 20nm silica. These experiments have been repeated in HPMVEC, but have been unsuccessful due to the cell sensitivity to the dye loading protocol.Figure 5:

Figure 6:

Figure 7:

Figure 8:

Figure 9:

Future Activities:

Journal Articles:

No journal articles submitted with this report: View all 3 publications for this subprojectSupplemental Keywords:

ambient air, ozone, exposure, health effects, human health, metabolism, sensitive populations, infants, children, PAH, metals, oxidants, agriculture, transportation, Air, Health, RFA, Risk Assessments, particulate matter, human health risk, toxicology, epidemiological studies, lung disease, long term exposure, RFA, Health, Air, Risk Assessments, particulate matter, lung disease, long term exposure, epidemiological studies, PM, toxicology

Progress and Final Reports:

Original AbstractMain Center Abstract and Reports:

R832414 UC Davis Center for Children's Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Subprojects under this Center: (EPA does not fund or establish subprojects; EPA awards and manages the overall grant for this center).

R832414C001 Project 1 -- Pulmonary Metabolic Response

R832414C002 Endothelial Cell Responses to PM—In Vitro and In Vivo

R832414C003 Project 3 -- Inhalation Exposure Assessment of San Joaquin Valley Aerosol

R832414C004 Project 4 -- Transport and Fate Particles

R832414C005 Project 5 -- Architecture Development and Particle Deposition

The perspectives, information and conclusions conveyed in research project abstracts, progress reports, final reports, journal abstracts and journal publications convey the viewpoints of the principal investigator and may not represent the views and policies of ORD and EPA. Conclusions drawn by the principal investigators have not been reviewed by the Agency.

Project Research Results

- Final Report

- 2009 Progress Report

- 2008 Progress Report

- 2007 Progress Report

- 2006 Progress Report

- Original Abstract

2 journal articles for this subproject

Main Center: R832414

128 publications for this center

64 journal articles for this center