Grantee Research Project Results

Final Report: Development of High-Throughput and Real-Time Methods for the Detection of Infective Enteric Viruses

EPA Grant Number: R833008Title: Development of High-Throughput and Real-Time Methods for the Detection of Infective Enteric Viruses

Investigators: Chen, Wilfred , Mulchandani, Ashok , Yates, Marylynn V. , Myung, Nosang V.

Institution: University of California - Riverside

EPA Project Officer: Page, Angela

Project Period: August 31, 2006 through August 30, 2009 (Extended to August 26, 2011)

Project Amount: $600,000

RFA: Development and Evaluation of Innovative Approaches for the Quantitative Assessment of Pathogens in Drinking Water (2005) RFA Text | Recipients Lists

Research Category: Drinking Water , Water

Objective:

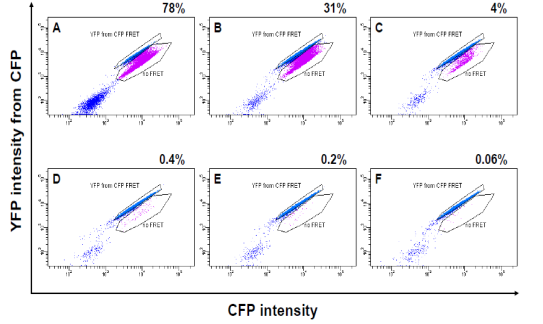

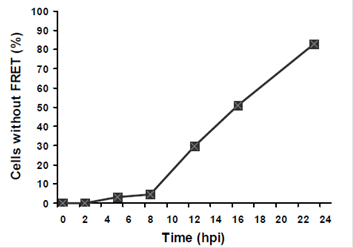

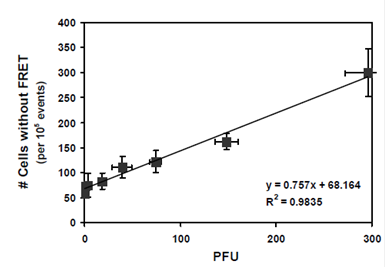

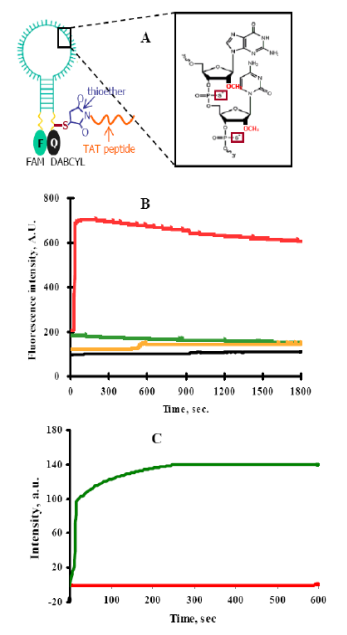

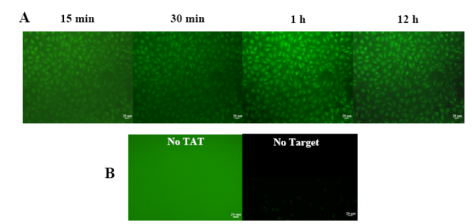

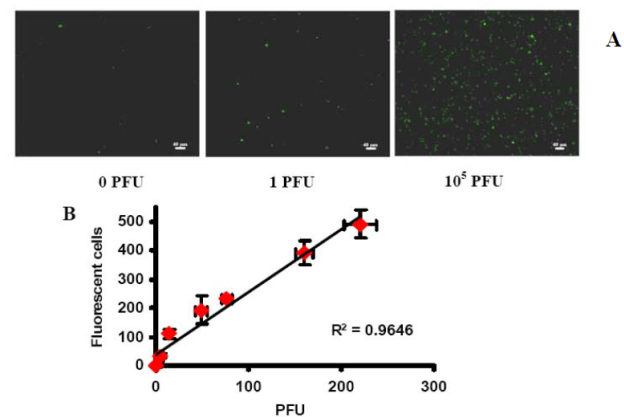

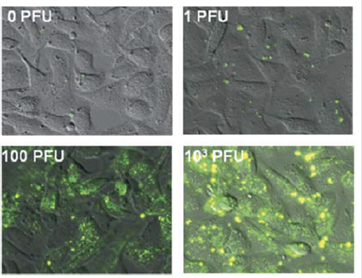

The main goal of this research is to improve on the current analytical methods for quantitative detection of infective enteric viruses, specifically the non-polio enteroviruses (NPEV), in drinking water. The overall objective of the research is to develop methods to provide high-throughput real-time detection and quantitation of infective enteric viruses from contaminated water. The specific objectives of this research are to: (1) develop a new generation of molecular beacons (MBs) based on quantum dots as the fluorophore and gold nanoparticles as the quencher for improved sensitivity and multiplexing capability; (2) develop a real-time method to probe and quantify infective enteric viruses using TAT- or transferrin-modified nuclease-resistant molecular beacons (MBs) in infected cell lines without permeabilization; (3) develop a genetically engineered cell line to probe and quantify infective enteric viruses by generating a protease-sensitive FRET protein pair using an improved CFP-YFP pair; (4) evaluate the use of flow cytometry for high-throughput sample processing; and (5) evaluate the above methods to rapidly detect and quantify the presence of infective NPEV in environmental water samples.

Summary/Accomplishments (Outputs/Outcomes):

Journal Articles on this Report : 7 Displayed | Download in RIS Format

| Other project views: | All 7 publications | 7 publications in selected types | All 7 journal articles |

|---|

| Type | Citation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

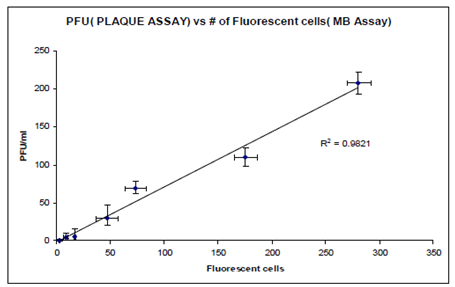

Cantera JL, Chen W, Yates MV. Detection of infective poliovirus by a simple, rapid, and sensitive flow cytometry method based on fluorescence resonance energy transfer technology. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2010;76(2):584-588. |

R833008 (Final) |

Exit Exit |

|

|

Cantera JL, Chen W, Yates MV. A fluorescence resonance energy transfer-based fluorometer assay for screening anti-coxsackievirus B3 compounds. Journal of Virological Methods 2011;171(1):176-182. |

R833008 (Final) |

Exit Exit Exit |

|

|

Hwang Y-C, Chu JJ-H, Yang PL, Chen W, Yate MV. Rapid identification of inhibitors that interfere with poliovirus replication using a cell-based assay. Antiviral Research 2008;77(3):232-236. |

R833008 (2008) R833008 (Final) |

Exit Exit |

|

|

Yeh H-Y, Yates MV, Chen W, Mulchandani A. Real-time molecular methods to detect infectious viruses. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology 2009;20(1):49-54. |

R833008 (Final) R828040 (Final) |

Exit Exit Exit |

|

|

Yeh H-Y, Hwang Y-C, Yates MV, Mulchandani A, Chen W. Detection of Hepatitis A virus using a combined cell culture-molecular beacon assay. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2008;74(7):2239-2243. |

R833008 (2008) R833008 (Final) |

Exit Exit Exit |

|

|

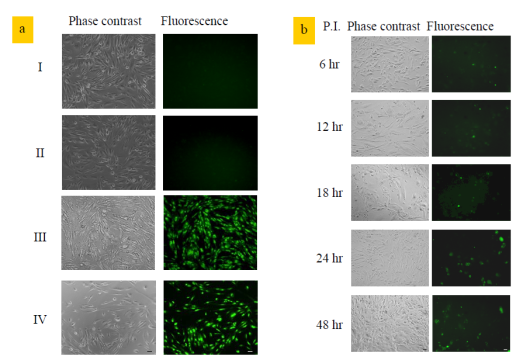

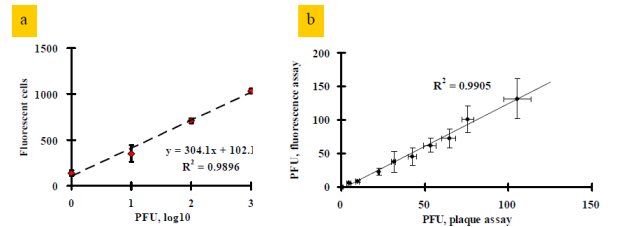

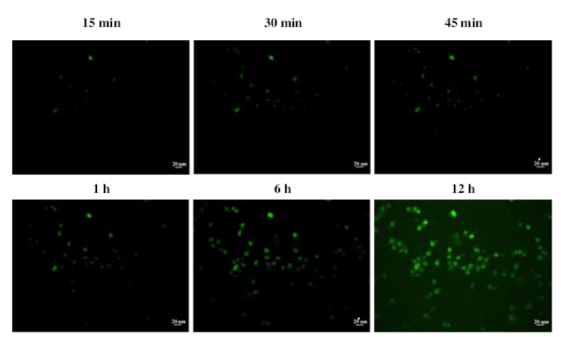

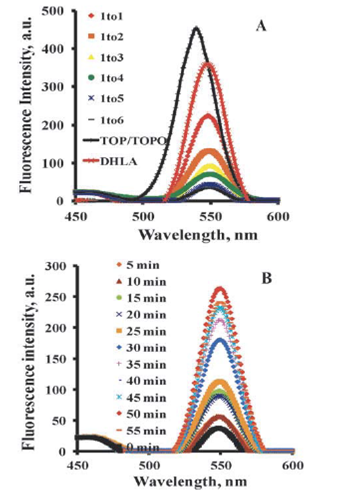

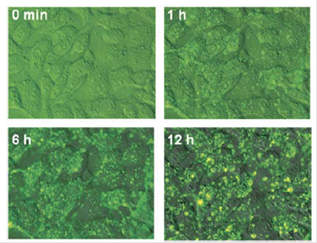

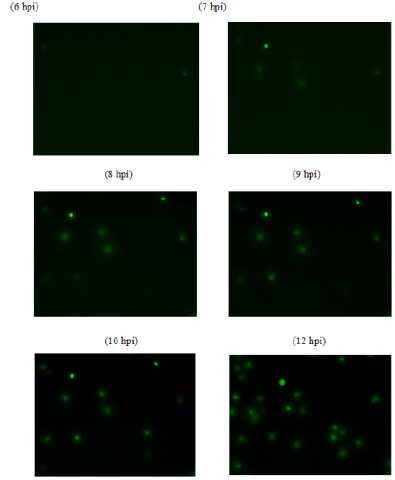

Yeh H-Y, Yates MV, Mulchandani A, Chen W. Visualizing the dynamics of viral replication in living cells via TAt peptide delivery of nuclease-resistant molecular beacons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2008;105(45):17522-17525. |

R833008 (2008) R833008 (Final) |

Exit Exit Exit |

|

|

Yeh H-Y, Yates MV, Mulchandani A, Chen W. Molecular beacon-quantum dot-Au nanoparticle hybrid nanoprobes for visualizing virus replication in living cells. Chemical Communications 2010;46(22):3914-3916. |

R833008 (Final) |

Exit Exit |

Supplemental Keywords:

RFA, Scientific Discipline, PHYSICAL ASPECTS, INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION, Water, POLLUTANTS/TOXICS, Health Risk Assessment, Physical Processes, Microbiology, Microorganisms, Drinking Water, health effects, human health, measurement method, viruses, microbiological organisms, monitoring, pathogens, drinking water contaminants, enteric viruses, exposure, drinking water monitoring, human health effectsProgress and Final Reports:

Original AbstractThe perspectives, information and conclusions conveyed in research project abstracts, progress reports, final reports, journal abstracts and journal publications convey the viewpoints of the principal investigator and may not represent the views and policies of ORD and EPA. Conclusions drawn by the principal investigators have not been reviewed by the Agency.