Grantee Research Project Results

Final Report: Development of Apparel and Footwear From Renewable Sources (Phase II)

EPA Grant Number: SU836007Title: Development of Apparel and Footwear From Renewable Sources (Phase II)

Investigators: Cao, Huantian , Wool, R. P. , Bonanno, Paula , Kramer, Jillian , Lipschitz, Stacey , Dan, Quan , Sidoriak, Emma , Zuckman, Emma , Cook, Henley , Gong, Shijin , Camara, Juliana , Woo, Andrew , Su, Xintian , Benz, Thomas

Institution: University of Delaware

EPA Project Officer: Page, Angela

Phase: II

Project Period: August 15, 2011 through August 14, 2013 (Extended to August 14, 2014)

Project Amount: $74,999

RFA: P3 Awards: A National Student Design Competition for Sustainability Focusing on People, Prosperity and the Planet - Phase 2 (2011) Recipients Lists

Research Category: Pollution Prevention/Sustainable Development , P3 Awards , P3 Challenge Area - Chemical Safety , Sustainable and Healthy Communities

Objective:

Leather and pleather (plastic leather, mainly polyurethane and polyvinyl chloride PVC) are widely used materials in apparel, footwear, and accessories. In 2008, the US consumption of footwear was 2.2 billion pairs, among which about one third (34%) were categorized as leather products and one third (34%) as plastic/vinyl products (AAFA, 2009). The chemical processes to convert raw animal hides to leather, especially tanning, cause environmental pollution and human health problems. Chromium salts are used in about 90% of global tanning production (Nair et al., 2012). The oxidizing product of tanning agent Chromium (III) is chromium (VI), a known toxin and carcinogen. PVC causes severe environmental problems and human health hazards through manufacture, use, and disposal. Dioxins, the most important by-products of the PVC lifecycle (Thornton, 2002), are persistent and bioaccumulative endocrine disruptive chemicals (EDCs), which represent a global threat to the health of human beings and wildlife (Bergman et al., 2013). Large quantities of phthalates (a few phthalates are EDCs) are added to PVC as plasticizers to make the plastics more flexible. Due to these problems, many nations, industries, and companies are trying to eliminate the use of PVC (Thornton, 2002).

To solve the environmental and human health problems related to leather and pleather, and provide apparel and footwear industry with environmentally friendly materials, we developed new breathable composites from natural fiber textiles and renewable, plant-based fatty acids. The composites could be used as environmentally friendly leather substitute (eco-leather). In Phase I (EPA SU834707) of the project, bio-based composites were developed and apparel and footwear prototypes were made. It was also found that eco-leather materials with different mechanical properties, color, and footwear with different styles were the areas for improvement (Cao et al., 2014). One judge for our Phase I project recommended to use the eco-leather materials to develop accessories such as bags, wallets, and purses. Phase II of the project focused on these improvements and developments.

The project is a multidisciplinary collaboration between faculty and students in the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering (CBE) and the Department of Fashion and Apparel Studies (FASH). CBE researchers developed composite materials from bio-based renewable sources, and FASH researchers used these materials from renewable sources to design, develop, and evaluate fashion products.

In this Phase II project, we continue our effort to develop apparel and footwear materials from renewable sources such as plant oils, and use these materials to develop more fashion products with different design and style. As in Phase I, we choose female college students as the target users for our design. Our objectives include: (a) developing and evaluating bio-based materials for apparel and footwear products; (b) designing and producing fashion products (footwear and accessories) with different styles using bio-based materials; (c) evaluating the comfort, consumers’ acceptance, and cost of our design and product; (d) evaluating the lifecycle environmental impacts of the materials, and (e) revising the design based on evaluation results and developing educational tool.

Summary/Accomplishments (Outputs/Outcomes):

Materials development and testing

The eco-leather material was a breathable composite made from textile fabric and bio-based renewable chemicals. After investigating a few renewable-sourced fibers such as organic cotton, flax, and SoronaTM (DuPont Co.), the researchers decided to focus on using organic cotton woven and knit fabrics as the substrate of the eco-leather composite. The bio-based renewable resin chemicals used in material development were acrylated epoxidized soybean oil (AESO), methacrylated lauric acid (MLAU), and dibutyl itaconate (DBI). AESO is synthesized through a reaction of acrylic acid and epoxidized soybean oil; MLAU is derived from palm seed oil; and DBI is derived from cellulose.

Two processing techniques, i.e., Resin Transfer Molding (Hot Press with high pressure) technique and Vacuum Assisted Resin Transfer Molding (VARTM) technique, were used in eco-leather development. In Resin Transfer Molding technique, half of the resin (50/50 AESO/MLAU or 50/50 AESO/DBI) was evenly spread on a peel ply film in the mold. Then the cotton fabric was placed on top of the resin and the other half of the resin was spread evenly on top. A second peel ply was placed on top and mold was covered with a lid. The mold was placed in the hot press and cured with pressure. The curing pressure (low or high), temperature and time (room temperature for 24 hours or 90 ºC for 2 hours) can be varied to develop different eco-leather composites. After that, the mold was placed in an oven at 120ºC for an additional 2 hours of post curing. In the VARTM process, the textile fabric was placed at room temperature into a large vacuum bag where the top and bottom molding surfaces were controlled for lustrous or matte appearance. A vacuum was drawn and the low viscosity natural oil resins (50/50 AESO/MLAU) infused into the fabric. The liquid resin fills both the gaps between fibers and also infuses through absorption in the interior of the fibers.

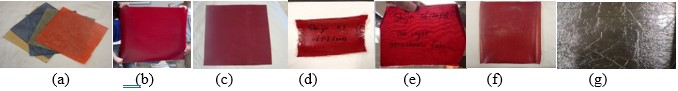

Eco-leather samples with different colors were developed by adding dyes in curing step, or using dyed cotton fabric in the composite development. It was found that using dyed cotton fabric in eco-leather development would give eco-leather a uniform color. A few eco-leather samples developed in this project are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Eco-leather from cotton fabric and resin composite - a. cotton woven fabric and AESO/MLAU (50:50) resin with dyes; b. dyed cotton woven fabric and AESO/MLAU (50:50) resin (high luster); c. dyed cotton woven fabric and AESO/MLAU (50:50) resin (matte); d. one-layer single knit fabric and AESO/MLAU (50:50) resin composite; e. two-layer single knit fabric and AESO/MLAU (50:50) resin composite; f. and g. one-layer single knit fabric and AESO/DBI (50:50) resin composite.

Materials testing experiments have been focused on the comfort and durability (mechanical) properties of the eco-leather materials. The comfort tests include measuring thermal resistance (Rct), evaporative resistance (Ret), and stiffness/softness of the samples. Rct and Ret data were measured by a sweating guarded hotplate in accordance with ASTM F1868 (Thermal and evaporative resistance of clothing materials using a sweating hot plate) standard. The stiffness/softness data were measured using a Handle-o-meter in accordance with ASTM D6828 (Stiffness of fabric by blade/slot procedure) standard. Durability tests include measuring abrasion resistance, tensile strength and elongation. Abrasion resistance data were measured using a universal wear tester in accordance with ASTM D3885 (Abrasion resistance of textile fabrics (flexing and abrasion method)) standard. Tensile strength and elongation data were measured using a tensile tester in accordance with ASTM D5034 (Breaking strength and elongation of textile fabrics) standard. For comparison, we purchased two genuine leather materials, i.e., pebble grain cowhide leather (3-3.5 oz) and Italian lambskin leather (1.5-2 oz), and tested comfort and durability performance.

The testing results of stiffness and abrasion resistance of six eco-leather materials (greige goods organic cotton woven fabric and 50/50 AESO/MLAU resin, as in Fig. 1(a)) are in Table 1. None of the six specimens ruptured after 3,000 cycles of abrasion. After 3,000 cycles of abrasion, the remaining thickness of eco-leather samples was in the range of 87.5% (No. 2) to 98.3% (No. 4) of original thickness. It was found that increasing eco-leather thickness would increase the stiffness. By adjusting the fabric thickness and amount of resin in eco-leather production, appropriate thickness and stiffness can be obtained for different applications.

Table 1. Thickness and stiffness testing results of eco-leather (woven organic cotton and AESO/MLAU composites)

| No | Original thickness (mm) | Stiffness (g) | Thickness (mm) after 3000 cycles of abrasion |

| 1 | 0.480 | 333.75 | 0.425 |

| 2 | 0.400 | 84.50 | 0.350 |

| 3 | 0.476 | 294.25 | 0.455 |

| 4 | 0.665 | >1,000 | 0.654 |

| 5 | 0.733 | >1,000 | 0.681 |

| 6 | 0.481 | 338.25 | 0.461 |

After developing footwear prototype (Fig. 3(a)), and testing material evaporative resistance (Ret), we found that eco-leather materials with enhanced stretchability and breathability (as indicated by Ret) performance were desired. Therefore, knit cotton fabrics were used in the composite development with AESO/DBI (50:50) resin. The samples were prepared by Resin Transfer Molding technique. The eco-leather samples are in Fig. 2(f) and (g).

Different pressures, low and high, were used in the Resin Transfer Molding technique to produce two eco-leather samples. Eco-leather 1 was developed using low pressure and eco-leather 2 was developed using high pressure. Testing results of the two eco-leather and two genuine leather samples are in Table 2. Due to different pressure used in composite development, eco-leather 1 had higher resin content (66.6%) and was thicker than eco-leather 2 (resin content 45.2%). Similar to the two leather materials, eco-leather 1 was considered water repellent with negative accumulative one-way transport index (OWTC). However, high variance was observed in the moisture management data for eco-leather 2 (among the 5 replicates in the test, 2 samples were water repellent and 3 samples were water permeable), indicating the resin in eco-leather 2 was not uniformly distributed due to low content. The low resin content in eco-leather 2 also resulted in very low evaporative resistance (Ret), which is considered the best breathability among the 4 samples. The Ret of eco-leather 1 was lower than the cowhide leather, but higher than the lambskin leather. The two eco-leather materials have much lower Rct data than leather. The users will feel cool when wearing products made from eco-leather.

Table 2. Comfort performance of eco-leather materials

|

| Thickness (mm) | Stiffness (g) | Rct (ºC·m2/W) | Ret (Pa·m2/W) | OWTC (%) | OMMC |

| Cowhide leather | 1.524 | 90.69 | 0.0236 | 112.10 | -853.1 | 0 |

| Lambskin leather | 1.080 | 25.94 | 0.0263 | 18.32 | -1160.4 | 0.0046 |

| Eco-leather 1 | 0.496 | 127.31 | 0.0033 | 52.41 | -720.1 | 0.0224 |

| Eco-leather 2 | 0.368 | 50.00 | 0.0097 | 8.86 | 114.6 | 0.4224 |

The external consultant (custom shoe maker) informed the researchers that thicker eco-leather is better in footwear products. The research team further evaluated the tensile strength and elongation of eco-leather 1. It was found that the tensile properties of eco-leather 1 (warp direction: tensile strength = 466.6 N, elongation = 20.92%; filling direction: tensile strength = 354.5 N, elongation = 48.22%) were also in the range of genuine leathers (cowhide leather: tensile strength = 1059 N, elongation = 53.0%; lambskin leather: tensile strength = 300.5 N, elongation = 57.4%).

Eco-leather made by single knit cotton fabric and AESO/DBI (50/50) resin has similar comfort and durability performance as genuine leather. In addition, eco-leather has much lower Rct than leather. While leather is a comfortable material for cold weather, eco-leather would be more comfortable for warm weather products such as summer shoes, or athletic products that require quick dissipation of body heat.

Product development and evaluation

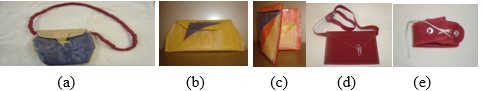

Following the recommendation of one judge for our Phase I project, we developed some accessories as illustrated in Figure 2. Using eco-leather sample (Figure 1(b)), a leading athletic footwear company helped the team develop a pair of shoes as in Figure 3(a). Based on the property of the eco-leather sample (Figure 1(g)), the team designed shoes, and worked with an external consultant (custom shoe maker) to make shoe prototypes as in Figure 3 (b) and (c).

Figure 2. Accessories made from eco-leather materials

Figure 3. Shoes made from eco-leather materials

Human subject survey, focus group and wear tests were designed to evaluate the user’s acceptance of eco-leather and fashion prototypes. The three testing protocols have been approved by the university’s Institutional Research Board prior to the testing. The two shoe prototypes (shoe 1 as in Fig. 3(b) and shoe 2 as in Fig. 3(c)) were evaluated in all three tests, and the handbag (Fig. 2 (d)) and bracelet (Fig. 2(e)) were also evaluated in the survey and focus group. All the participants were female students in the university. Eight-four students completed the survey; 13 students participated in the focus group discussions, and 8 students participated in the wear test.

The survey participants were randomly separated into two groups. Half of the participants were educated about the renewable bio-based materials, and the positive effects on the environment, and the other half participants did not have the “sustainability education” part. The survey used 7-point Likert scales with 7 as “extremely good”. The survey results are in Table 3. The participants positively rated the quality, feel/hand, and texture of the eco-leather made from knit cotton fabrics (Fig 1(f)), and overall appearance and comfort of the two shoe prototypes. The participants who were given the materials sustainability education gave higher ratings than those who were not, but the differences were not significant (p>0.05) for most of the questions.

The wear test used 5-point Likert scales with 5 as “being the most/best” or “strongly agree”. The participants in the wear test thought eco-leather (Fig. 1(f)) was suitable for shoe upper material (avg. ratings 3.75 for shoe 1 and 3.5 for shoe 2). Participants considered shoe 1 more “fashionable” (avg. rating = 3.875) than shoe 2 (avg. rating = 2.625). Though the two shoes were designed and developed for the same size (size 7), shoe 1 was easier to adjust for different feet, resulting in different ratings for fit (avg. rating 3.125 for shoe 1 and 1.625 for shoe 2). This may be one of the reasons that after wearing and walking, the overall comfort rating was neutral (avg. rating = 3.0) for shoe 1 and negative for shoe 2 (avg. rating = 2.0).

Similar to survey and wear test, focus group results indicated shoe 1 design (Fig. 3(b)) is better accepted by college students than shoe 2 design (Fig 3(c)). One participant commented shoe 2 “is not for my age.” Most focus group participants also comments they liked the “eco-friendly” or “sustainability” characteristics of eco-leather and shoes.

The survey and focus group results indicated the handbag and bracelet were less accepted than the shoes. However, quite a few participants indicated they liked the color of eco-leather used in handbag and bracelet. Developing eco-leather with a variety of colors was a major improvement from phase I of the project.

Table 3. Survey results for eco-leather and prototypes (7-point Likert scale)

| Question | with education | w/o education | t-test p-value | ||

| Mean | σ | Mean | σ | ||

| 1. Rate the quality of eco-leather in handbag/bracelet (Fig 1(c)) | 3.86 | 1.49 | 3.21 | 1.60 | 0.06 |

| 2. Rate overall appearance of handbag (Fig 2(d)) | 3.21 | 1.42 | 2.90 | 1.59 | 0.35 |

| 3. Rate overall appearance of bracelet (Fig 2(e)) | 3.40 | 1.68 | 3.07 | 1.55 | 0.35 |

| 4. Rate the quality of eco-leather in shoes (Fig 1(f)) | 5.10 | 1.22 | 4.76 | 1.25 | 0.22 |

| 5. Rate feel/hand of eco-leather in shoes (Fig 1(f)) | 5.29 | 1.27 | 4.93 | 1.30 | 0.20 |

| 6. Rate texture of eco-leather in shoes (Fig 1(f)) | 5.29 | 1.17 | 5.00 | 1.21 | 0.27 |

| 7. Rate overall appearance of shoe 1 (Fig 3(b)) | 5.38 | 1.45 | 4.88 | 1.53 | 0.13 |

| 8. Rate the comfort level of shoe 1 (Fig 3(b)) | 5.10 | 1.23 | 4.49 | 1.17 | 0.03 |

| 9. Rate overall appearance of shoe 2 (Fig 3(c)) | 4.69 | 1.62 | 4.37 | 1.48 | 0.34 |

| 10. Rate the comfort level of shoe 2 (Fig 3(c)) | 4.86 | 1.38 | 4.49 | 1.23 | 0.22 |

Conclusions:

Using chemicals from plants, i.e., AESO, DBI, MLAU, and organic cotton fabrics, as the starting materials, eco-leather composites can be developed with comfort and mechanical properties comparable to genuine leather. These starting chemicals are renewably sourced from soybean oil (AESO), cellulose (DBI) and palm seed oil (MLAU), and have low cost. To produce one square meter of eco-leather, one square meter of cotton fabric ($2/square meter of the single knit organic cotton fabric), and approximately $2 AESO and $3.5 DBI were used, resulting in the total material cost of $7.5. It should be noted that these material costs were for small scale laboratory production. The large-scale mass production cost can be significantly lower.

The development of eco-leather is beneficial to people, prosperity, and the planet. In addition to the advantage of bio-based feedstock, eco-leather are environmentally benign substitute. Using organic cotton ensured no harmful pesticides and synthetic fertilizers were used in cotton fiber production. Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS) indicate neither AESO nor DBI is identified as probable, possible or confirmed human carcinogen. DBI is non-hazardous, while the only hazard concern for AESO was that it may cause an allergic skin reaction. Compared with DBI, MLAU may cause mild skin irritation and respiratory irritation. This was the reason that since year 2 of the project, we have focused on using AESO/DBI resin rather than AESO/MLAU resin in eco-leather development.

Using non-hazardous bio-based feedstock as the starting materials to make apparel and footwear products allow us to be more responsible toward the human population. The environmental problems related to conventional apparel and footwear materials such as water contamination from leather tanning processes, toxic pollutants related to PVC production, and using depleting petroleum resources for synthetic materials, can be eliminated. The workers in industry will not be exposed to the harmful toxins produced from the leather tanning, PVC manufacturing, and other processes. The consumer will have affordable, durable, and comfortable apparel and footwear products that do not contain harmful components, and have longer using time.

The bio-based feedstock materials are inexpensive and renewable alternatives to petroleum-based materials, which will help industry save cost. In addition, companies will be able to save cost because they will not have to pay for the disposal of the toxins created during the leather tanning, and PVC manufacturing process.

This project enhanced educational experiences for FASH and CBE students. FASH students learned cutting-edge materials developed for fashion industry and used them in product development to solve real-world problems. This research experience helped strengthen their STEM (Science, Technology. Engineering, and Mathematics) skills. CBE students also learned from this project with a better understanding of material requirements from a product design and development perspective. To have a broader impact, this project was discussed in required core courses (Fundamental of Textiles I and II) for FASH majors, and exhibited nationally (e.g., National Sustainable Design Expo) and on university campus (e.g., UD Sustainability Day).

References:

- AAFA (2009). Trends: an annual statistical analysis of U.S. apparel and footwear industries (annual 2008 edition). Available from: https://www.wewear.org/assets/1/7/Trends2008.pdf.

- Bergman, Å, Heindel, J.J., Jobling, S., Kidd, K.A., Zoeller, R.T. (2013). State of the science of endocrine disrupting chemicals ─ 2012. World Health Organization and United Nations Environmental Programme. (http://www.who.int/ceh/publications/endocrine/en/)

- Cao, H. Wool, R., Bonanno, P., Dan, Q., Kramer, J., & Lipschitz, S. (2014). Development and evaluation of apparel and footwear made from renewable bio-based materials. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education, 7(1), 21-30.

- Nair, A.D.G., Hansdah, K., Dhal, B., Mehta, K.D., & Pandey, B.D. (2012). Bioremoval of Chromium (III) from model tanning effluent by novel microbial isolate. International Journal of Metallurgical Engineering, 1(2), 12-16.

- Thornton, J. (2002). Environmental impact of polyvinyl chloride building materials (ISBN 0-9724632-0-8). Healthy Building Network.

Journal Articles:

No journal articles submitted with this report: View all 6 publications for this projectSupplemental Keywords:

Environmentally benign substitute, bio-based feedstock, textile, toxic use reductionProgress and Final Reports:

Original AbstractP3 Phase I:

Development of Apparel and Footwear From Renewable Sources | Final ReportThe perspectives, information and conclusions conveyed in research project abstracts, progress reports, final reports, journal abstracts and journal publications convey the viewpoints of the principal investigator and may not represent the views and policies of ORD and EPA. Conclusions drawn by the principal investigators have not been reviewed by the Agency.