Grantee Research Project Results

Final Report: Evaluation of Mobile Source Emissions and Trends Using Detailed Chemical and Physical Measurements

EPA Grant Number: R834553Title: Evaluation of Mobile Source Emissions and Trends Using Detailed Chemical and Physical Measurements

Investigators: Harley, Robert A. , Goldstein, Allen H.

Institution: University of California - Berkeley

EPA Project Officer: Chung, Serena

Project Period: April 1, 2010 through March 31, 2014

Project Amount: $500,000

RFA: Novel Approaches to Improving Air Pollution Emissions Information (2009) RFA Text | Recipients Lists

Research Category: Particulate Matter , Air , Climate Change

Objective:

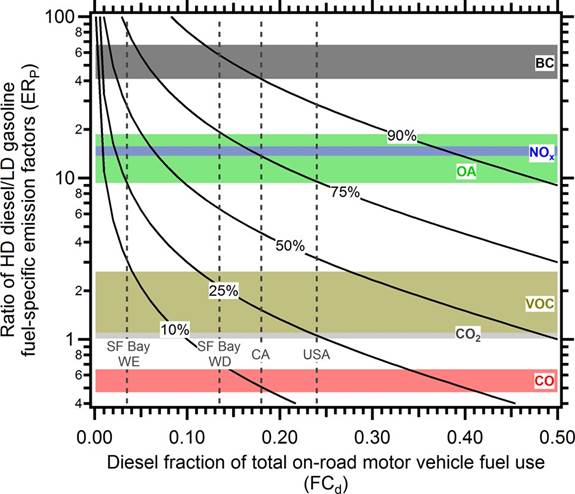

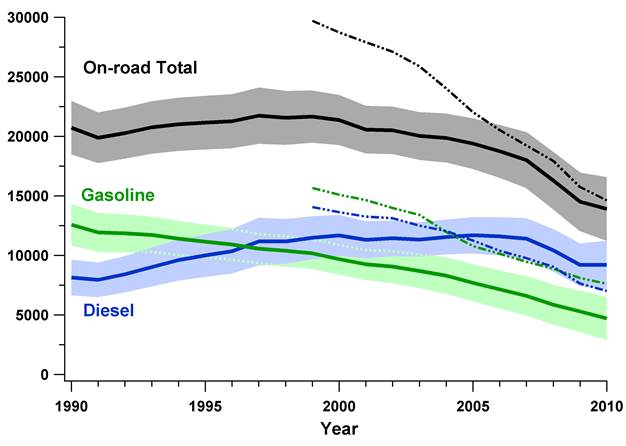

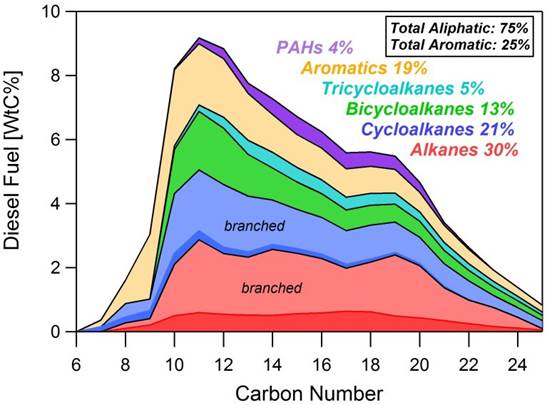

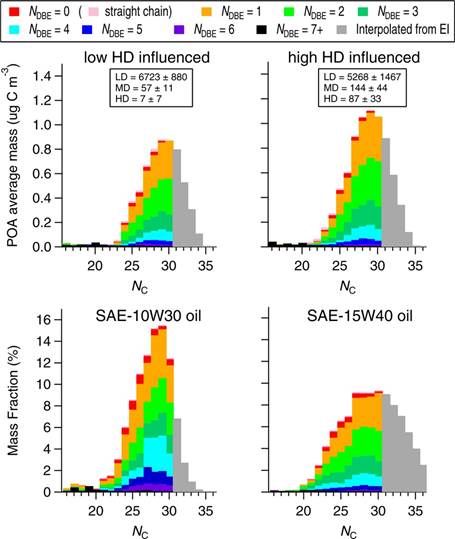

The overall objective of this project was to evaluate on-road motor vehicle emissions of air pollution, and trends in these emissions over time. Both gasoline and diesel engine emissions were measured, and there was special emphasis on characterizing emission factor distributions for pollutants emitted by heavy-duty diesel trucks. We address questions of the relative importance of gasoline versus diesel contributions to overall emissions from all on-road motor vehicles. Also exhaust particulate emissions have been characterized in much greater detail than has been reported previously. This research is included as a major element in a field study that was conducted in summer 2010 to measure current on-road diesel and gasoline vehicle emission rates and exhaust composition. The field study, and subsequent reporting of results highlight the use of new methods and instrumentation for enhanced characterization of emission factor distributions.

Summary/Accomplishments (Outputs/Outcomes):

Journal Articles on this Report : 9 Displayed | Download in RIS Format

| Other project views: | All 19 publications | 9 publications in selected types | All 9 journal articles |

|---|

| Type | Citation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Chan AWH, Isaacman G, Wilson KR, Worton DR, Ruehl CR, Nah T, Gentner DR, Dallmann TR, Kirchstetter TW, Harley RA, Gilman JB, Kuster WC, de Gouw JA, Offenberg JH, Kleindienst TE, Lin YH, Rubitschun CL, Surratt JD, Hayes PL, Jimenez JL, Goldstein AH. Detailed chemical characterization of unresolved complex mixtures in atmospheric organics:insights into emission sources, atmospheric processing, and secondary organic aerosol formation. Journal of Geophysical Research:Atmospheres 2013;118(12):6783-6796. |

R834553 (Final) |

Exit Exit |

|

|

Dallmann TR, DeMartini SJ, Kirchstetter TW, Herndon SC, Onasch TB, Wood EC, Harley RA. On-road measurement of gas and particle phase pollutant emission factors for individual heavy-duty diesel trucks. Environmental Science & Technology 2012;46(15):8511-8518. |

R834553 (2012) R834553 (Final) |

Exit Exit Exit |

|

|

Dallmann TR, Kirchstetter TW, DeMartini SJ, Harley RA. Quantifying on-road emissions from gasoline-powered motor vehicles:accounting for the presence of medium-and heavy-duty diesel trucks. Environmental Science & Technology 2013;47(23):13873-13881. |

R834553 (Final) |

Exit Exit Exit |

|

|

Dallmann TR, Onasch TB, Kirchstetter TW, Worton DR, Fortner EC, Herndon SC, Wood EC, Franklin JP, Worsnop DR, Goldstein AH, Harley RA. Characterization of particulate matter emissions from on-road gasoline and diesel vehicles using a soot particle aerosol mass spectrometer. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2014;14(14):7585-7599. |

R834553 (Final) |

Exit Exit |

|

|

Gentner DR, Isaacman G, Worton DR, Chan AW, Dallmann TR, Davis L, Liu S, Day DA, Russell LM, Wilson KR, Weber R, Guha A, Harley RA, Goldstein AH. Elucidating secondary organic aerosol from diesel and gasoline vehicles through detailed characterization of organic carbon emissions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2012;109(45):18318-18323. |

R834553 (2012) R834553 (Final) |

Exit Exit Exit |

|

|

Gentner DR, Worton DR, Isaacman G, Davis LC, Dallmann TR, Wood EC, Herndon SC, Goldstein AH, Harley RA. Chemical composition of gas-phase organic carbon emissions from motor vehicles and implications for ozone production. Environmental Science & Technology 2013;47(20):11837-11848. |

R834553 (Final) |

Exit Exit Exit |

|

|

McDonald BC, Dallmann TR, Martin EW, Harley RA. Long-term trends in nitrogen oxide emissions from motor vehicles at national, state, and air basin scales. Journal of Geophysical Research:Atmospheres 2012;117(D21):D00V18 (11 pp.). |

R834553 (2012) R834553 (Final) |

Exit Exit |

|

|

Wood EC, Knighton WB, Fortner EC, Herndon SC, Onasch TB, Franklin JP, Worsnop DR, Dallmann TR, Gentner DR, Goldstein AH, Harley RA. Ethylene glycol emissions from on-road vehicles. Environmental Science & Technology 2015;49(6):3322-3329. |

R834553 (Final) |

Exit Exit Exit |

|

|

Worton DR, Isaacman G, Gentner DR, Dallmann TR, Chan AWH, Ruehl C, Kirchstetter TW, Wilson KR, Harley RA, Goldstein AH. Lubricating oil dominates primary organic aerosol from motor vehicles. Environmental Science & Technology 2014;48(7):3698-3706. |

R834553 (Final) |

Exit Exit Exit |

Supplemental Keywords:

Gasoline, diesel, nitrogen oxides, particulate matter, carbon monoxide, formaldehyde, nitrogen dioxide, volatile organic compounds, primary organic aerosol, secondary organic aerosol, organic carbon, black carbon, aerosol mass spectrometerProgress and Final Reports:

Original AbstractThe perspectives, information and conclusions conveyed in research project abstracts, progress reports, final reports, journal abstracts and journal publications convey the viewpoints of the principal investigator and may not represent the views and policies of ORD and EPA. Conclusions drawn by the principal investigators have not been reviewed by the Agency.