Grantee Research Project Results

2009 Progress Report: A Novel Molecular-Based Approach for Broad Detection of Viable Pathogens in Drinking Water

EPA Grant Number: R833011Title: A Novel Molecular-Based Approach for Broad Detection of Viable Pathogens in Drinking Water

Investigators: Meschke, John Scott , Cangelosi, Gerard A.

Institution: University of Washington , Seattle Biomedical Research Institute

EPA Project Officer: Aja, Hayley

Project Period: July 3, 2006 through July 2, 2009 (Extended to August 31, 2010)

Project Period Covered by this Report: July 3, 2008 through July 2,2009

Project Amount: $597,987

RFA: Development and Evaluation of Innovative Approaches for the Quantitative Assessment of Pathogens in Drinking Water (2005) RFA Text | Recipients Lists

Research Category: Drinking Water , Water

Objective:

The objective of this research is to develop and evaluate a novel, molecular-based approach for broad detection and enumeration of viable pathogens in drinking water.Progress Summary:

Viruses adsorbed to positively charged filters were eluted with 1.5% beef extract containing 0.05M glycine with 0.01% vol./vol. Tween 80, adjusted to pH 9.5 or OptimaRE. Later experiments with adenovirus incorporated sodium polyphosphates in the eluant for improved recovery. OptiCap filters were rinsed with 500 mL of 0.5 mM H2SO4 (pH 3.0) and eluted with 350 mL of 1 mM NaOH (pH 10.8) and neutralized with 3 mL of 50 mM H2SO4 and 100 μL of 100x Tris-EDTA buffer (pH 8.0) according to a protocol adapted from Katayama, et al. (2002). Percent recovery from filters was determined by comparison of viral titer of the influent to the viral titer of the eluate.

|

Water Type

|

Filter

|

N*

|

Mean ( ± St. Dev)

|

|

|

DI Water

|

ViroCap

|

23

|

65

|

( ± 23)

|

|

|

Virosorb 1MDS

|

3

|

30

|

( ± 10)

|

|

Artificial Seawater

|

ViroCap

|

16

|

63

|

( ± 13)

|

|

|

OptiCap XL

|

3

|

15

|

( ± 4.5)

|

|

Virus Type

|

Filter

|

N*

|

Mean ( ± St. Dev)

|

|

|

DI Water

|

ViroCap

|

6

|

37

|

( ± 12)

|

|

|

Virosorb 1MDS

|

3

|

51

|

( ± 5.8)

|

|

Artificial Seawater

|

ViroCap

|

6

|

44

|

( ± 25)

|

|

|

OptiCap XL

|

3

|

11

|

( ± 2.8)

|

|

Matrix

|

N*

|

Mean ( ± St. Dev)

|

|

|

Groundwater

|

3

|

44

|

( ± 6.6)

|

|

Surface water

|

3

|

53

|

( ± 4.1)

|

|

Seawater

|

3

|

51

|

( ± 0.3)

|

The novel ViroCap capsule filter is a promising, low-cost, alternative to current cartridge and capsule filters. Recoveries of coliphage MS2 from deionized water using the ViroCap filter were significantly greater than recoveries using the standard 1MDS filter, and poliovirus recoveries were comparable. The ViroCap filter was uninhibited by natural matrices and showed consistent recoveries from groundwater, surface water, and seawater.

Microbial contamination decreased significantly (p<0.05) during the dry season for TC, E. coli, and MsC (Figure 2). Median TC contamination was 104.3 CFU/ 100 mL for the rainy season; in the dry season there was a half log10 reduction in contamination and an overall decrease in the variability found between samples. E. coli median contamination was 103.2 CFU/100 mL and decreased by one log10 into the dry season. MsC were present at 102.2 PFU/10 mL eluate, representing the virus recovered from one liter of filtered water.

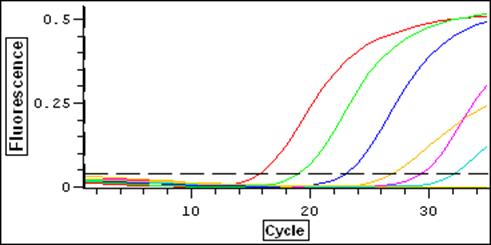

Green and Yellow = True Positives Red and Blue = False Positives

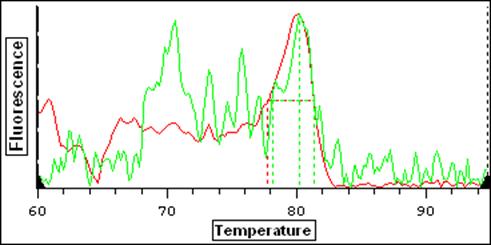

Red = True Positive Tm Green = False Positive Tm

Future Activities:

- Develop additional target sequences for our RPA method;

- Continue nucleic acid extraction work on microfluidic cards (e.g. evaluation of different eluant types, and scaling up of volume processed);

- Begin integration of filtration and nucleic acid extraction; and

- Continue development of the ICC-qRT-PCR targeting the negative strand of HEV-B.

Journal Articles:

No journal articles submitted with this report: View all 16 publications for this projectSupplemental Keywords:

Progress and Final Reports:

Original AbstractThe perspectives, information and conclusions conveyed in research project abstracts, progress reports, final reports, journal abstracts and journal publications convey the viewpoints of the principal investigator and may not represent the views and policies of ORD and EPA. Conclusions drawn by the principal investigators have not been reviewed by the Agency.