Grantee Research Project Results

2024 Progress Report: Modelling outdoor comfort with UAV-based digitization technique and a comfort tracking system for underserved communities

EPA Grant Number: SU840584Title: Modelling outdoor comfort with UAV-based digitization technique and a comfort tracking system for underserved communities

Investigators: Karimi, Maryam , Nazari, Rouzbeh , Rabbani, Fahad

Institution: The University of Alabama at Birmingham

EPA Project Officer: Cunniff, Sydney

Phase: I

Project Period: August 1, 2023 through May 9, 2025

Project Period Covered by this Report: August 1, 2023 through July 31,2024

Project Amount: $25,000

RFA: 19th Annual P3 Awards: A National Student Design Competition Focusing on People, Prosperity and the Planet Request for Applications (RFA) (2022) RFA Text | Recipients Lists

Research Category: P3 Awards , P3 Challenge Area - Sustainable and Healthy Communities

Objective:

Climate change has noticeable adverse effects on cities and human health worldwide, with the urban heat island (UHI) being one of the major issues exacerbated by climate change (Sabrin et al., 2020; Dwivedi, 2022). The term "Urban Heat Island" (UHI) refers to the phenomena in which the air temperature in an urban region is greater than its surroundings (EPA, 1997) due to high thermal load, inadequate ventilation, reduction in vegetation, and rapid land use conversion from green spaces to commercial and residential sectors. This latter issue changed physical properties, such as albedo, surface roughness, evapotranspiration, and energy flux, which alter microclimate systems (Enteria et al., 2021; Ramly et al., 2023; Ren et al., 2023). The impact of UHIs can be significant even within city blocks as Karimi et al. (2015) observed temperature differences of up to 10°C between city blocks. Moreover, UHIs substantially influence mesoscale air circulation, leading to convection and precipitation (Yandra, 2023). In addition to influencing local weather patterns and interacting with air pollution, it was recently reported that UHI has a direct impact on health via heat exposure. This can exacerbate mild diseases, impair occupational performance, or increase the risk of hospitalization and even death (Heaviside, 2020). Additionally, it was stated by previous studies that increased hospital admissions, asthma attacks, and acute respiratory symptoms were the main outcomes of exposure to heat (Kenny et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2024). In this regard, the National Weather Service (NWS) has published online statistics of nationwide summary of deaths and injuries due to natural hazards since 1996. According to the NWS report (2023), extreme temperatures led to 218 fatalities in the U.S., primarily due to heat-related incidents. Since adequate heating is necessary, while air conditioning is not, the proportion of deaths from heat waves is substantially greater than those caused by cold weather. It has been demonstrated once temperatures rise over a particular threshold, mortality becomes more sensitive to modest temperature variations (Yandra, 2023). Therefore, UHIs become a global concern for several reasons, including increased human mortality and disease (Gabbe et al., 2023), air pollution (Ulpiani, 2021), and degradation of water surface quality (Vujovic et al., 2021), changes in frequency and duration of precipitation (Oh et al., 2023), ecosystem and infrastructure damage (Wang et al., 2021), and increased energy consumption (Yang et al., 2023). Temperature and a population's sensitivity to temperature vary locally and are factors in acute respiratory illness. Public health issues and environmental harm are the most alarming of the hazards UHIs pose (Sabrin et al., 2020). Three primary components contribute to the risk of injury from a UHI consist of occurrence, exposure, and vulnerability (Lanlan et al., 2024). Since the extent and intensity of a certain UHI are very localized, localized research must be carried out to identify UHIs and their effects on communities.

The goal of this project is to propose an integrated monitoring system of outdoor comfort by understanding the underserved neighborhoods air quality. Currently, there is no device available that is designed to monitor localized comfort conditions, particularly when people are exposed to external heat and poor air quality. The system will incorporate methods for measuring thermal comfort indices and air quality at the local level in designated especially sensitive districts of Birmingham, Alabama. Information of urban canopy and air pollution level will be collected by community campaign before simulating, modeling an integrated comfort index and sharing the results with the underserved community via an informative mobile application system. This project can help with Birmingham’s air quality and mitigate with UHI effect by:

1. Identifying the most vulnerable priority neighborhoods struggling to tackle heat events and air pollution from nearby sources.

2. Quantifying fine resolution impacts of the built environment and surface properties on surrounding temperature and air quality.

3. Collecting and measuring climate data from nearby stations and air pollution onsite data collection at the finest resolution by engaging community via voluntary campaigns.

4. Developing an application for comfort tracking and simulating alternative scenarios for the residents to be engaged and raise awareness.

5. Characterizing the need for urban green infrastructure or better urban planning, maximizing the cooling and pollution absorbing benefit.

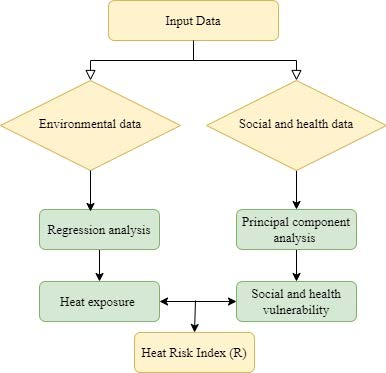

To achieve the main goal of this project, three models were developed to analyze heat-related vulnerabilities: the Principal Component Analysis (PCA) Index, which integrates socio-demographic and health data to capture vulnerability; the Exposure Risk Index (E), which evaluates environmental exposure risks, particularly Land Surface Temperature (LST); and the Heat Risk Index (R), which combines the PCA and Exposure Risk Index to assess heat risk based on social, demographic, and health factors. Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression was used to examine key environmental variables, with multicollinearity tests used to exclude dependent variables like NDVI and albedo. To account for geographical relationships, a geographical Autoregression (SAR) model was used, which was evaluated for appropriateness using Moran's I test. The SAR model generated global impact values that were used as index weights, thereby detecting substantial connections between Land Surface Temperature (LST) and heat risk indicators throughout Jefferson County census block groupings (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Methodology (Source: Authors).

Progress Summary:

This study applied spatial analysis in its investigation of urban heat on the physical landscape of Birmingham and the vulnerability of different communities that will be affected by such changes.

Heat Exposure Risk and Heat Risk Index (E and R Index)

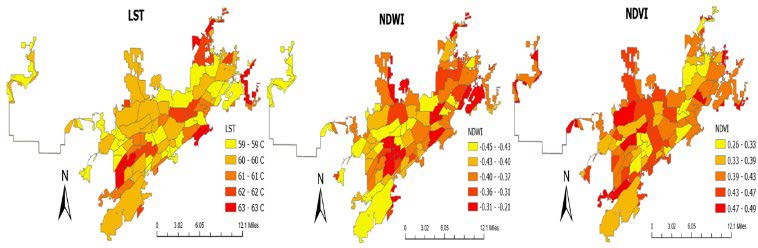

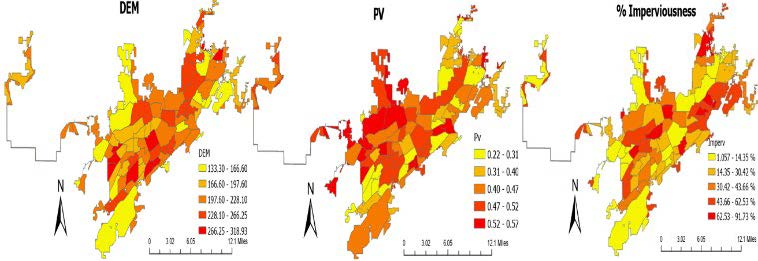

Land Surface Temperature (LST) was used to relate heat exposure to environmental impacts through vegetation, NDWI, and impervious surfaces as well as through elevation. The study now showed that impervious surfaces greatly increased LST compared to NDWI and vegetation that reduced LST while using SLX spatial model. The exposure risk (E Index) is derived from global impact coefficients calculated and standardized into 0-100 while high-risk areas occur close to city centers. Now, combining it with the V Index, the Heat Risk Index (R Index) paints Birmingham's inner city zone as a thick urban core with heat risk, with low-risk areas found at the periphery of the city. Targeted heat mitigation measures should be instituted to such high-risk urban blocks (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 2. Environmental parameters mapped over Jefferson County. 1. LST; 2. NDWI; and 3. NDVI. (Source: Authors).

Figure 3. Environmental parameters mapped over Jefferson County (Source: Authors).

Health and Social Vulnerability (V Index)

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is utilized in this project to assess the socioeconomic and health factors contributing to vulnerability across Jefferson County. Some of the most prominent health indicators include stroke, diabetes, asthma, obesity, high blood pressure, and lack of health insurance, along with social indicators such as degree of English proficiency, population density, age demographics, Black racial identity, disability, and lack of vehicle access. The vulnerability is indexed into the vulnerability index (V Index), which normalized the results of the PCA into a scale of 0-100, further visualized in a map of varying vulnerability levels across census tracts. The analysis so far indicated concentration in vulnerability in the Black and Hispanic communities, specifically indicating Birmingham city, and the importance of interventions directed at such policies (Figure 4 and Figure 5).

Figure 4. Social parameters mapped over Birmingham City: population with disability; population over 65; population density; Hispanic population; population over 65 lives alone; Black population; unemployment; people without vehicle; and population below poverty (Source: Authors).

Figure 5. Health parameters mapped over Birmingham city (Source: Authors).

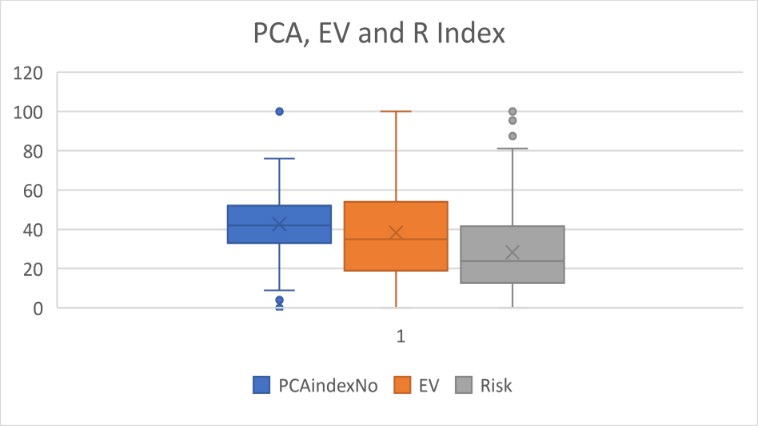

Findings showed that economically disadvantaged people, particularly the immigrants and minorities, children as well as elderly over 65 years old bear the brunt of heat exposure. Patterns in PCA, EV, and Risk Indexes have revealed in this area higher vulnerability to poverty and unemployment significantly contributing to economic and heat-related susceptibility, especially in predominantly black neighborhoods (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Distribution of PCA, E, and V index values resulted for Birmingham City Census tracts (Source: Authors).

Future Activities:

Based on the research findings, it was found that it is important to place parks and green spaces strategically among urban areas in order to improve air quality and the well-being of the community. They provide physical indicators that employed climate and temperature data along with vegetation cover and infrastructure location in generating maps to guide planners planning to create more efficient urban developments for Birmingham. Data and created maps are then available online for quick access via an informative webpage hosted by University of Alabama Birmingham (UAB). Overall, the study indicates strategic community approaches to assessing vulnerable populations. In addition, it shows the ability of green infrastructure to mitigate heat effects in cities on such at-risk populations.

References:

Dwivedi, M. C. (2022). Assessing the socioeconomic implications of climate change. Cosmos: An International Journal of Art and Higher Education, 11(2), 20-23.

United States Environmental Protection Agency. (1997). Climate change and New Jersey (EPA 230-F-97-008dd). U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. https://www.epa.gov.

Gabbe, C. J., Mallen, E., & Varni, A. (2023). Housing and urban heat: Assessing risk disparities. Housing Policy Debate, 33(5), 1078-1099. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2022.2093938.

Karimi, M., Nazari, R., Vant-Hull, B., & Khanbilvardi, R. (2015). Urban heat island assessment with temperature maps using high resolution datasets measured at street level. The International Journal of the Constructed Environment, 6(4), 17-28. https://doi.org/10.18848/2154-8587/CGP/v06i04/37455.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. (2023). Summary of Natural Hazard Statistics for 2023 in the United States. https://www.weather.gov/media/hazstat/sum23.pdf.

Oh, S. G., Han, J. Y., Min, S. K., & Son, S. W. (2023). Impact of urban heat island on daily and sub-daily monsoon rainfall variabilities in East Asian megacities. Climate Dynamics, 61(1), 19-32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-023-06792-3

Ramly, N., Hod, R., Hassan, M. R., Jaafar, M. H., Isa, Z., & Ismail, R. (2023). Identifying vulnerable populations in urban heat islands: A literature review. International Journal of Public Health Research, 13(2), 45-58.

Ren, J., Shi, K., Kong, X., & Zhou, H. (2023). On-site measurement and numerical simulation study on characteristics of urban heat island in a multi-block region in Beijing, China. Sustainable Cities and Society, 95, 104615. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2023.104615

Sabrin, S., Karimi, M., Fahad, M. G. R., & Nazari, R. (2020). Quantifying environmental and social vulnerability: Role of urban heat island and air quality, a case study of Camden, NJ. Urban Climate, 34, 100699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2020.100699

Yandra, B. S. K. (2023). Creating cool and equitable communities: A comprehensive study on urban heat island mitigation and health equity in Birmingham, Alabama (Master’s thesis, The University of Alabama at Birmingham). University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Journal Articles on this Report : 4 Displayed | Download in RIS Format

| Other project views: | All 9 publications | 4 publications in selected types | All 4 journal articles |

|---|

| Type | Citation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Sabrin, S., Karimi, M., & Nazari, R. (2022). Modeling heat island exposure and vulnerability utilizing earth observations and social drivers:A case study for Alabama, USA. Building and Environment, 226, 109686. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2022.109686. |

SU840584 (2024) |

not available |

|

|

Sabrin, S., Karimi, M., Nazari, R., Pratt, J., & Bryk, J. (2021). Effects of different urban-vegetation morphology on the canopy-level thermal comfort and the cooling benefits of shade trees:A case study in Philadelphia. Sustainable Cities and Society, 66, 102684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2020.102684. |

SU840584 (2024) |

not available |

|

|

Sabrin, S., Karimi, M., & Nazari, R. (2023). The cooling potential of various vegetation covers in a heat-stressed underserved community in the deep south:Birmingham, Alabama. Urban Climate, 51, 101623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2023.101623. |

SU840584 (2024) |

not available |

|

|

Karimi, M., Nazari, R., Fahad, M. G. R., & Sabrin, S. (2022). Impact of the built environment on near-surface temperatures in complex urban settings. SSRN. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4181530. |

SU840584 (2024) |

not available |

Progress and Final Reports:

Original AbstractThe perspectives, information and conclusions conveyed in research project abstracts, progress reports, final reports, journal abstracts and journal publications convey the viewpoints of the principal investigator and may not represent the views and policies of ORD and EPA. Conclusions drawn by the principal investigators have not been reviewed by the Agency.