Grantee Research Project Results

Final Report: Occurrence, fate, transport, and treatment of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in landfill leachate

EPA Grant Number: R839670Title: Occurrence, fate, transport, and treatment of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in landfill leachate

Investigators: Guelfo, Jennifer

Institution: Texas Tech University

EPA Project Officer: Hahn, Intaek

Project Period: August 1, 2019 through July 31, 2022 (Extended to July 31, 2024)

Project Amount: $500,000

RFA: Practical Methods to Analyze and Treat Emerging Contaminants (PFAS) in Solid Waste, Landfills, Wastewater/Leachates, Soils, and Groundwater to Protect Human Health and the Environment (2018) RFA Text | Recipients Lists

Research Category: Drinking Water , Water Quality , Human Health , Water , PFAS Treatment

Objective:

An estimated 61.1 million m3yr-1 of leachate is generated in the United States. Studies suggest that most leachates contain per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) that may pose a risk to human health and/or the environment following release of raw or treated leachate. This project addressed three primary objectives: 1) optimization of strategies for analysis of total PFAS composition and concentrations in field-collected landfill leachate using a combination of analytical techniques; 2) assessment of sorption, desorption, and diffusion of a select set of PFAS in representative flexible membrane and clay liner materials and evaluate impacts of solution chemistry on these processes; and 3) evaluation of the impacts of leachate conditions on the rate and efficacy of total PFAS degradation using ultrasound treatment and determine optimal reactor configuration and operational parameters based on landfill conditions and treatment goals.

Summary/Accomplishments (Outputs/Outcomes):

Objective 1: Objective 1 was focused on optimization of strategies for cleanup of field-collected landfill leachate samples including:

• Solvent dilution, liquid-liquid extraction (LLE), and solid-phase extraction (SPE) sample preparation approaches for targeted analysis and high resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) analysis using high performance liquid chromatography quadrupole time of flight mass spectrometry (LC-QTOF-MS).

• Optimization of the total oxidizable precursor (TOP) assay for use with landfill leachate.

• Evaluation of TOP assay, combustion ion chromatography (CIC), and HRMS for understanding total PFAS composition and concentrations in landfill leachate.

• Application of optimized methods to field-collected landfill leachate samples.

Initial efforts focused on three preparation methods: 1) a previously published liquid-liquid extraction (LLE); 2) a previously published solid phase extraction (SPE) approach using weak anion exchange (WAX); and solvent dilution. Later in the project, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) issued Method 1633 for use with media including leachate, so this approach was added for some samples at the midpoint of the project. Comparison results demonstrated that optimal preparation approaches for leachate may differ by sample and will depend on the analytical method applied (Table 1). For targeted analysis, solvent dilution (when possible), LLE, and EPA 1633 preparation approaches led to similar data quality. Care should be taken when selecting a method for use with HRMS analysis and suspect screening or non-targeted data analysis since our data demonstrated that SPE methods using WAX cartridges may not retain all PFAS. This could lead to false negatives, and also result in lower measurements of total organic fluorine.

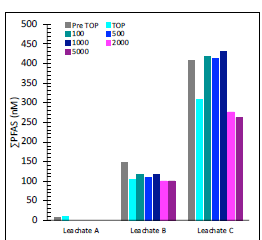

Efforts to optimize the TOP assay for use on leachates led to inconclusive results. TOP was implemented using concentrations of 80-300 mM K2SO8 with 170-800 mM NaOH. Even maximum K2SO8 concentrations failed to fully oxidize precursors in all leachate samples, and in some cases led to decreases in total molar PFAS concentrations (Figure 2), perhaps resulting from incomplete precursor conversion to unmonitored intermediates and/or terminal, ultra short chain perfluoroalkyl carboxylates (PFCAs, e.g., trifluoroacetic acid). A second oxidation step was added to try and improve TOP outcomes. This used an initial oxidation with 100-5000 mg/L of H2O2 and a second oxidation using 300 mM K2SO8 with 800 mM NaOH (Figure 2). Addition of an initial oxidation using 100-1000 mg/L of H2O2, decreased the residual precursors left following oxidation and losses in total molar precursors. However, none of the leachate samples exhibited increases in total molar PFAS following the two-step TOP assay, which was somewhat unexpected. Results suggest that unknown precursors are not present in samples, precursors are present that do not oxidize to monitored endpoints, or unknown precursors are present that are recalcitrant to oxidation. Total organic fluorine concentrations are further discussed below.

Figure 1. PFAS (nM) detected after TOP assay in Leachate A (80 mM K2SO8, 170 mM NaOH) and Leachates B-C (300 mM

K2SO8, 800 mM NaOH) and after 2-step oxidation of Leachates B-C.

| Method | Advantages | Disadvantages | Best suited fora |

| Solvent Dilution | Less time Low cost No PFAS exclusion | Matrix interference some samples No sample concentration No removal of inorganic F; may interfere with CIC analysis | Cleaner leachate samples [PFAS] > laboratoryspecific limits of detection Targeted, HRMS analysis, CIC if inorganic F is low |

| LLE | Mid-range time and cost Easily implemented (no clogging; see EPA 1633) Extracts PFAS with varied chain length, charge Achieves data quality similar to EPA 1633 Removes inorganic F | Extraction solvent is 10% (v/v) 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol in ethyl acetate- adds organic F to samples Background organic F has to be background subtracted from CIC results | Leachates higher in matrix components (most) Targeted, HRMS analysis CIC only if background subtraction of organic F is suitable for analysis |

| EPA 1633 | Greatest time and cost Suitable primarily for retention of anionic, neutral, and some zwitterionic PFAS Removes inorganic F; no organic F added during extraction | Hardest to implement Easily clogs during extraction; requires (20x) leachate dilution or multiple SPE cartridges Sample concentration possible if clogging challenges can be addressed May lead to false negatives during HRMS analysis1 | Leachates higher in matrix components (most) and/or that need concentration Targeted, CIC analysis |

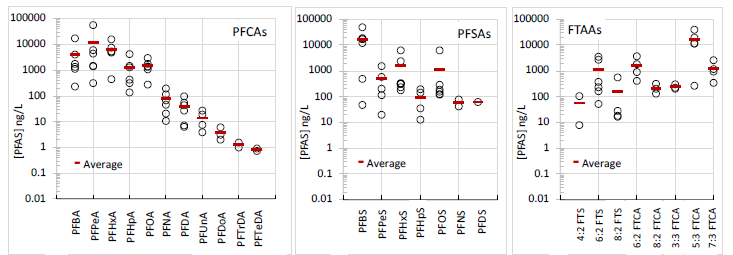

Acronyms: Combustion ion chromatography (CIC); high resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS)- used here to denote analysis intended for suspect screening or non-targeted data analysis; liquid liquid extraction (LLE). 1. Based on suspect screening evaluations done with a solid phase extraction weak anion exchange extraction similar to but pre-dating EPA 1633. Evaluation using EPA-1633 needed for further evaluation. Optimized sample preparation approaches were used to characterize six field-collected leachate samples (Leachates A-D and 1-2) from anonymous locations in the US. Average PFAS concentrations detected in all leachates were ~1 ng/L (perfluorotetradecanoic acid or PFTeDA detected in 33% of samples) to 16,481 ng/L (5:3 fluorotelomer carboxylate or 5:3 FTCA detected in 83% of samples; Figure 2). Although 5:3 FTCA had the highest average concentration, perfluorobutane sulfonate (PFBS) had essentially the same average level (16,371 ng/L) and was detected in 100% of samples. Overall, the sum of targeted PFAS led to concentrations in the 1,000s-100,000s of ng/L dominated by short-chain PFCAs, perfluoroalkyl sulfonates (PFSAs) and n:3 FTCAs. Actual total PFAS concentrations may be higher where “unknown” PFAS are present as further discussed below.

Figure 2. Concentrations (ng/L; log scale) of perfluoroalkyl carboxylates (PFCAs), perfluoroalkyl

sulfonates (PFSAs) and n:2 and n:3 fluorotelomer acids (FTAAs) measured in six field-collected landfill

leachates from unknown locations in the US.

As noted in the discussion of sample preparation, TOP assay results raised questions about the occurrence of unmonitored or “unknown” PFAS in leachates. The lack of increase in total molar PFAS following oxidation could be attributed to a lack of unknown PFAS, but this merits validation via other methods given other questions described regarding the TOP results. HRMS with suspect screening data processing (Leachates A-C) and CIC (Leachates D, 1-2) were also explored to evaluate the unknown PFAS, or unknown organofluorine in the case of CIC. The latter distinction is made because non-PFAS sources of organofluorine may be captured by CIC. PFAS were detected in all leachates analyzed using LC-HRMS at estimated concentrations of <2 to >100,000 ng/L. In all three leachate samples, more PFAS were detected in samples prepared by LLE vs. SPE-WAX. These efforts pre-dated EPA 1633, so similar evaluations using EPA 1633 would be beneficial. Suspect PFAS detected in leachates prepared by LLE included: 1.59 (PFOSi) to 1520 (10:2 FTKS) ng/L in Leachate A, 5.83 (PFEtCHxS) - 21,658 (BPr-FPrAd) ng/L in Leachate B, and 1.94 (H-PFENS) - 61,351 (H-PFEPeS) ng/L in Leachate C. Results suggest that TOP assay increases should have been observed provided oxidation resulted in complete transformation of precursors to terminal PFCAs.

CIC analysis also posted challenges for leachate analysis. Whereas LLE preparation introduces background organic F, leachate samples prepared by SPE require extensive dilution to avoid clogging the SPE cartridge. The latter reduces total fluorine concentrations to levels below the limit of detection for organic F by CIC (0.5 mg/L) for many leachates unless large volumes of dilute leachate are prepared. Regardless of method, there is no internal standard for use in CIC analysis, which makes it challenging to correct for extraction efficiency. In the current work, samples were prepared using centrifugation, modification with 10% methanol, and direct analysis by CIC. Organic F concentrations in Leachates 1 and 2 were below detection, but 1.7 mg/L of organic fluorine were detected in Leachate D. In total, targeted analytes could account for only 8% of organic F, suggesting that >90% is unidentified. This fraction could be comprised of PFAS or non-PFAS sources of organic F (e.g., pharmaceuticals) as noted above. Overall, the project results highlighted multiple sample preparation approaches for targeted analysis and suspect screening, but suspect screening concentrations are, at best, an estimate. Therefore, total PFAS (or total organic F) analytical approaches with sufficient sensitivity to successfully quantify concentrations across all leachates (which vary widely) with more certainty still remains a challenge.

Objective 2. This objective focused on evaluation of sorption and diffusion of PFAS through materials used in engineered landfill liner systems. These systems are typically comprised of a flexible geomembrane layer (FML) and clay layer (e.g., bentonite). In some cases, these are used in repeated layers to create a barrier between the landfill and the underlying subsurface. In this project, sorption and diffusion were collectively evaluated in polypropylene linear low density polyethylene (LLDPE), LLDPE modified with ethylene vinyl alcohol (EVOH), bentonite, and fluorosorb. Sorption was measured in batch systems and diffusion was evaluated in side-by-side diffusion cells separated by the membrane of interest. In FML materials sorption of PFAS was generally chain length dependent and followed the trend of PP < LLDPE+EVOH < LLDPE. In clay materials, sorption of PFAS most commonly detected in leachate to bentonite was low (Kd ≤ 1 L/kg for PFAS up to 9-10 fluoroalkyl carbons). Conversely, sorption of PFAS in fluorosorb was difficult to assess due to complete uptake of PFAS from the aqueous phase. A primary goal of these experiments was to evaluate sorption coefficients are needed to calculate effective diffusivity (Deff) through membrane materials. As further described below, this need was most critical for the fluorosorb material, but due to complete uptake, values were unavailable. As a result, sorption coefficients to fluorosorb were modeled, and evaluation of sorption coefficients to this material would be ideal in future studies.

Side by side diffusion cells with LLDPE and LLDPE+EVOH were conducted with Leachate C and membranes extruded specifically for this project to a thickness of 0.1 and 0.01 mm, respectively. These thicknesses were selected so that diffusion could be observed in a reasonable time frame. Prior studies of LLDPE+EVOH at 0.01 mm demonstrated PFOS breakthrough in ~6 months, but no PFAS breakthrough in either membrane was observed in the current project for the duration of the experiments (~1 year). Results demonstrate that intact FMLs should be very protective against PFAS breakthrough when used in liner systems.

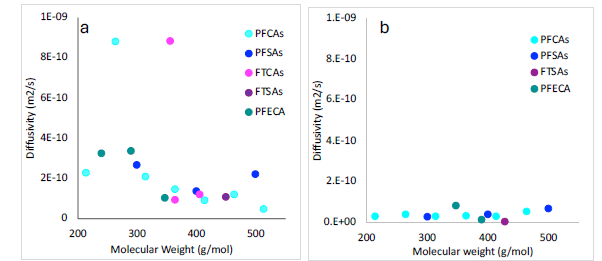

Diffusion experiments with bentonite exhibited rapid breakthrough of PFAS in leachate into through the material and into the unimpacted water in the receiving side of the cell. In bentonite, PFAS breakthrough occurred in Day 1 and was approaching steady state at the end of the experiment (Day 80). Due to low sorption, it was not necessary to account for retardation (i.e., R ≅ 1). Values of Deff were ~9x10-10 (PFPeA, 5:3 FTCA) to ~5x10-11 m2/s (PFDA), generally decreased with increasing molecular weight, and did not show clear trends with functional group (Figure 3a). These values are similar to those measured for volatile organic compounds in prior studies, suggesting that these liner materials will have similar efficacy for PFAS retention.

Diffusion experiments with fluorosorb also exhibited rapid breakthrough of PFAS, but trends differed from the anticipated increasing concentrations in the receiving cell over time. Instead, breakthrough occurred at initial high concentrations and then decreased with time. In the source side, concentrations exhibited the anticipated decrease in concentration over time. Modeling efforts support a hypothesis rapid, initial intermixing of leachate from the source into the receiving side occurred because fluorosorb does not exhibit swelling equivalent to bentonite (e.g., high permeability). Diffusivities were modeled using the decrease in concentrations in the source side. As result of strong sorption to fluorosorb, measured Kd values would be ideal in separating effective diffusion and sorption during non-steady state, but complete uptake of PFAS occurred in fluorosorb batch sorption experiments. Therefore, fluorosorb models used diffusivity in water modified for porosity and determined Kd as a fitted parameter. As a result of retardation, Deff in fluorosorb were lower than bentonite (Figure 3b). Lack of swelling and high sorption underscore the utility of fluorosorb as an additional layer in liner systems, and not as an alternative to low permeability clays such as bentonite.

Objective 3. This objective focused on viability of ultrasound treatment (i.e. sonolysis) for treatment of PFAS-contaminated landfill leachate through evaluation of impacts of leachate conditions on treatment rate and efficacy of total PFAS degradation using synthetic leachate. These evaluations require 14L of leachate for each round of experimentation conducted using the sonolysis reactor. Leachates A-D were limited in volume, but sonolysis was evaluated using 14L of a separate leachate available at a partner university. Results demonstrated that sonolysis was not effective for degradation of PFAS in leachate without further modifications (e.g., sonolysis coupled with other treatment approaches), which was beyond the scope of this work.

Figure 3. Effective diffusivities (Deff) in a) bentonite and b) fluorosorb.

Journal Articles on this Report : 1 Displayed | Download in RIS Format

| Other project views: | All 13 publications | 3 publications in selected types | All 3 journal articles |

|---|

| Type | Citation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Shojaei M, Kumar N, Guelfo J. An integrated approach for determination of total per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Environmental Science & Technology 2022;56(20):14517-14527. |

R839670 (2021) R839670 (2022) R839670 (2023) R839670 (Final) |

Exit Exit |

Supplemental Keywords:

PFAS, solid waste, leachate, landfills, sorptionProgress and Final Reports:

Original AbstractThe perspectives, information and conclusions conveyed in research project abstracts, progress reports, final reports, journal abstracts and journal publications convey the viewpoints of the principal investigator and may not represent the views and policies of ORD and EPA. Conclusions drawn by the principal investigators have not been reviewed by the Agency.

Project Research Results

- 2023 Progress Report

- 2022 Progress Report

- 2021 Progress Report

- 2020 Progress Report

- Original Abstract

3 journal articles for this project