Grantee Research Project Results

2011 Progress Report: Photochemical and Fungal Transformations of Carbon Nanotubes in the Environment

EPA Grant Number: R834858Title: Photochemical and Fungal Transformations of Carbon Nanotubes in the Environment

Investigators: Jafvert, Chad T. , Fairbrother, D. Howard , Filley, Timothy

Institution: Purdue University , The Johns Hopkins University

EPA Project Officer: Hahn, Intaek

Project Period: August 15, 2010 through August 14, 2013

Project Period Covered by this Report: May 1, 2011 through May 1,2012

Project Amount: $600,000

RFA: Increasing Scientific Data on the Fate, Transport and Behavior of Engineered Nanomaterials in Selected Environmental and Biological Matrices (2010) RFA Text | Recipients Lists

Research Category: Chemical Safety for Sustainability

Objective:

We have proposed that due to their size, any transformation of carbon nanotubes (CNTs) in the environment is likely dominated by abiotic oxidative and extracellular microbial processes. Consequently, in this study we are investigating the photochemical and fungal mediated transformations that occur to colloidal and solid phase CNTs. Our goal is to identify transformation products, reaction kinetics, and reaction mechanisms, including the effects of coupled photochemical-fungal exposures.

Our objectives are based on two overarching hypotheses: (i) Photochemical and fungal transformations of CNTs will occur and proceed via oxidative processes with important consequences for their overall persistence in the environment, and (ii) that the rate of these reactions will depend on CNT physicochemical properties (e.g., surface properties), environmental conditions (e.g., pH, fungi type), and CNT form (e.g., colloids or immobilized in polymers).

Progress Summary:

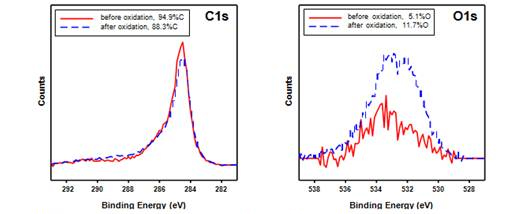

Figure 1. XPS spectra of carbon 1s and oxygen 1s regions before and after oxidation with

70% nitric acid on SG-65 carbon nanotubes

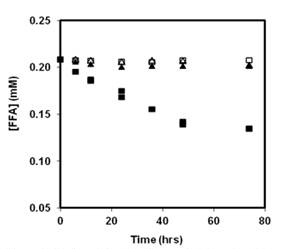

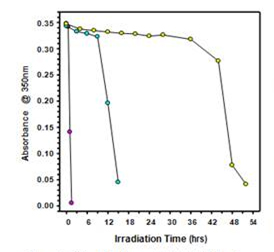

Figure 2. FFA loss indicating 1O2 production at pH7

in lamp light (λ = 350 ± 50 nm) by aqueous dispersions

of P3-COOH (■), and oxidized SG-6 5 (▲), and the

corresponding dark control samples of P3-COOH □),

and oxidized SG-65 (△).

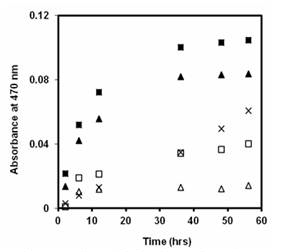

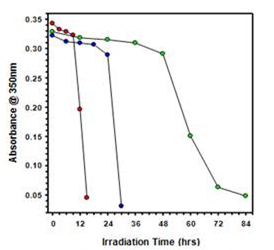

In a similar experiment, XTT was employed as a superoxide anion scavenger to quantify the production of this ROS. Reaction of XTT with O2.- produces a product that strongly absorbs light at 470 nm, allowing confirmation of superoxide anion production by UV-Vis spectroscopic analysis. Figure 3 shows that aqueous dispersions of P3-COOH and oxidized SG-65 containing XTT generate the reaction product more rapidly than XTT or nanotube control sample, indicating superoxide anion is produced by both types of oxidized tubes. Employing pCBA as a hydroxyl radial (∙OH) scavenger indicates greater production of ∙OH by P3-COOH than oxidized SG-65, but greater production by both types of CNTs compared to all control samples. These data (Figures 2 and 3 and pCBA experiments) are strong preliminary evidence that metal impurity concentrations or species type (i.e., nickel vs. molybdenum), the extent of surface oxidation, or even the tube diameter or roll up angle, control the extent and type of ROS produced under sunlight by carbon nanotubes.

Figure 3. Evidence of O2 production by XTT (0.1 nM)

products formation under lamp light (λ = 350 ± 50 nm)

in aqueous suspenstions of : P3-COOH with XTT (▲),

oxidized SG-65 with XTT (■), and XTT alone (x) and the

corresponding dark controls.

Figure 4. A typical example of MWCNTs

irridated by UV light, the control (left) which

was wrapped in aluminum foiil and the sample

exposed to light (right) where the CNTs have

aggregated and precipitated to the bottom of

the flask.

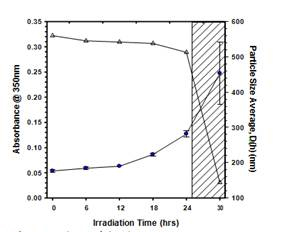

Figure 5. Relation of absorbance measurements

to particle size in determining aggregation period

of MWCNTs and pH7 and 3mM phosphate buffer

under UV irridation with 8 bulbs. Absorbance data

is plotted as open triangles and particle size measurements

are plotted as filled circles.

Figure 6. Effect of pH on collodial stability of MWCNTs while under irridation with UV light at 254 nm: pH4 (pink), pH7 (cyan), and pH10 (yellow) |  Figure 7. Effect of bulb intensity on the collidal stability of MWCNTs while under irridation with UV light at 254nm: 16 bulbs (red), 8 bulbs (blue), and 4 bulbs (green) |

Based on these preliminary studies our current efforts are focused on understanding the reasons for the UV-induced aggregation, with the hypothesis that it is mediated by photo-decarboxylation. To test this hypothesis, we are conducting studies with larger reactors where we can irradiate sufficiently large quantities of O-MWCNTs to facilitate analysis of the post-irradiated samples with X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), carried out in conjunction with chemical derivatization to assay the distribution of oxygen-containing functional groups.1-4 Similar XPS analysis will be conducted on CNTs irradiated with sunlight.

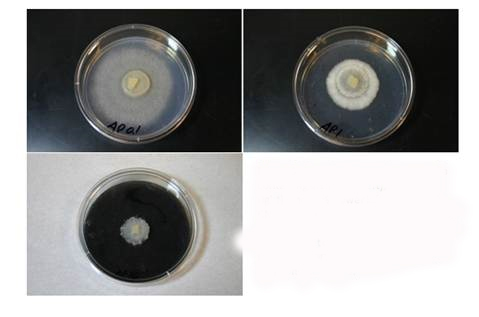

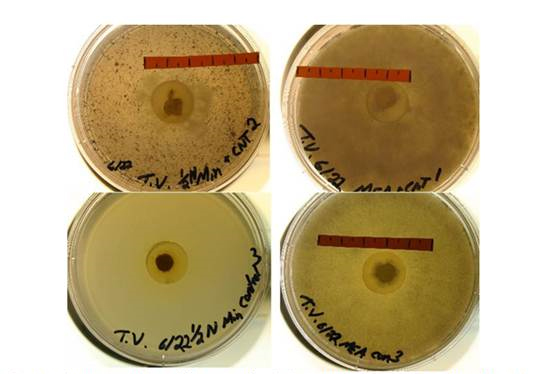

Figure 8. T. versicolor growing on media containing 0.1 (upper left), 1.0 (upper right)

, and 10% (lower left) unprufied CNT by mass. CNTs used on these plates are Carbon

Solutions, Inc. AP-CNT. Note confinement of growth to the disk of non-CNT's starter

media at the highest CNT concentrations.

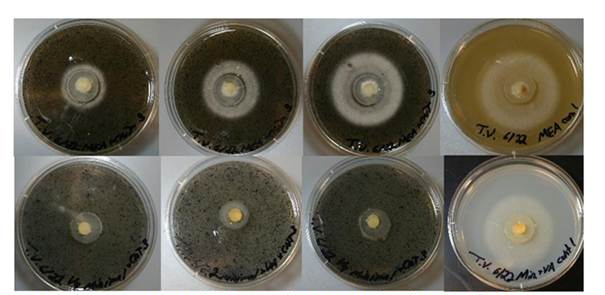

Figure 9. Phoset depicting possible mitigation of AP-CNT toxicity based on media additives. Top row:

malt extract agar +5% ATP-CNT after 5, 6, and 7 days growth, and the control plate of the same media

without ATP-CNT after 7 days. Bottom row: minimal media with veratyl alcohol +5% ATP-CNT after 5,

6, and 7 days, and the corresponding control plate after 7 days growth.

Figure 10. Photo inset exhibiting differences in fungal colony morphology based on media

and AT-CNT supplementation. Nitrogen limited media supports confluent, but very light

growtn (bottom left) malt extract media (bottom right) supports confluent growth of moderate

density. Addition of AP-CNT causes more selective growth with tendril-like rhizomorphs

on nirtigen limited media (top left) while fungus on AP-CNT malt agar chows very dense

confluent growth. (Major graduation = 1cm)

Future Activities:

References:

Journal Articles on this Report : 1 Displayed | Download in RIS Format

| Other project views: | All 31 publications | 11 publications in selected types | All 11 journal articles |

|---|

| Type | Citation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Chen C-Y, Jafvert CT. The role of surface functionalization in the solar light-induced production of reactive oxygen species by single-walled carbon nanotubes in water. Carbon 2011;49(15):5099-5106. |

R834858 (2011) R834858 (Final) |

Exit |

Supplemental Keywords:

Carbon nanotubes, nanotechnology, environmental photochemistry, fungi, trace gas analysis, transformation, waterRelevant Websites:

Progress and Final Reports:

Original AbstractThe perspectives, information and conclusions conveyed in research project abstracts, progress reports, final reports, journal abstracts and journal publications convey the viewpoints of the principal investigator and may not represent the views and policies of ORD and EPA. Conclusions drawn by the principal investigators have not been reviewed by the Agency.