Human-Made Changes

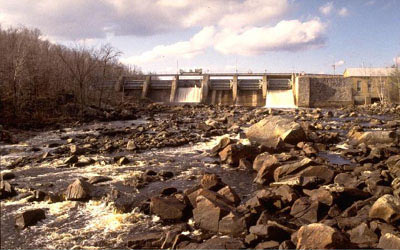

Human-induced Change Processes: Modification of River FlowLand uses such as urbanization, agriculture and timber harvest in watersheds change runoff and flow in significant indirect ways, but this section specifically addresses how river flow is modified directly when water is impounded or diverted. In many cases, impoundment and water withdrawal occur together with the result that flow amplitude is reduced, baseflow variation increases, temperature regime is altered, and mass transport of materials declines. When these things occur, overall connectivity between upstream and downstream reaches and between the river and its floodplain are compromised. This has a detrimental effect on biodiversity and ecological processes. These effects are significant across much of North America. Approximately 3,500,000 river miles were once free flowing; of this, 500,00 to 600,000 miles (14 to 17% of total) are now behind dams. 1,523 hydropower projects are currently operating under FERC license or exemption but approximately 60,000 dams are found in the United States (source: FERC). Although many of these dams are small they do have an impact on the flow regime of rivers and streams. Only 312 significant streams in the lower 48 States (0.4% of the total U.S. river mileage) are still free flowing and undeveloped in their entirety. None of the 15 large rivers in the continental United States (mean annual discharges > 350 m3/sec.) are unaffected by human impoundment and diversions.

Even where dams exist, they can often be operated in a manner to that more closely mimics natural flow regimes. For more on this topic, visit the Watershed Academy Web module Protecting Instream Flows: How Much Water Does a River Need? (Note: to return to this module after viewing the other site, simply click the back button), Although it is unlikely that it will be possible or desirable to operate a dam in a manner entirely consistent with a natural flow regime, measures can be taken to both stabilize base flows and ensure flows necessary to reconfigure channels and transport and exchange sediment. Lack of periodic high flows in the Colorado River's Grand Canyon justified a carefully planned "flushing flow" water release, designed to restore habitat types that had been affected by the altered sediment dynamics caused by the dam.

Flow regime, however, is not the only aspect of a river affected by dams. Dissolved oxygen, sediment transport and habitat are also affected.

Downstream temperature can also experience significant changes in response to dam operation. Reservoirs in temperate latitudes typically stratify as lakes do, with a warm surface epilimnion layer and a cold, dense hypolimnion in the depths. Dams that release surface water tend to increase annual temperature variation whereas dams that release deep water will tend to decrease annual temperature variation. Substantial biological consequences can result from altered temperature regimes and related changes in dissolved oxygen. Dams also act as sediment traps that limit downstream sediment delivery, with mixed effects on downstream habitat. In the arid Southwest, for example, non-native trout fisheries are now present at the base of dams that release cold clear water into river channels that were once filled with warm, sediment-laden water.

![[logo] US EPA](https://www.epa.gov/epafiles/images/logo_epaseal.gif)