Economic Costs

The economic costs of unplanned or poorly planned growth might not be recouped by the resulting tax base. Communities nationwide have found that low-density, disconnected layouts in residential subdivisions are inefficient and that many costs associated with the long-term operation and maintenance of service infrastructure that is extended out to these subdivisions might not be fully accounted for up front. The city of Fresno, California, has doubled in size since 1980, producing $56 million in yearly revenues, according to the Sierra Club. Yet the costs of services has risen to $123 million, not including costs for roads and sewers.

New residential development demands more in services than it contributes in taxes, and existing residents typically foot the bill. A comparative study of two townships in central Michigan shows that for every $1 in revenue, residential development costs were $1.20 or $1.47 while farmland and open forest land required only $0.24 or $0.27. Farmland and open space conservation also have indirect positive tax benefits, such as reducing costs for flood control and water supply, and add to the aesthetic value and character of a community, often capitalized in land value.

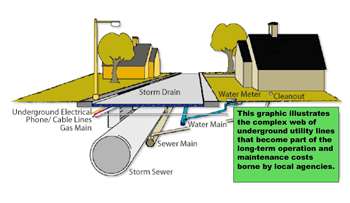

Typical service and utility infrastructure for new developments includes: roads, wastewater pipelines, street storm sewer drainage systems, drinking water pipelines, street lighting, trash collection, street sweeping, landscaping and mowing, snow plowing, fire services, and other civic amenities such as public transportation, schools and utilities. Many of these costs are borne by local governments and are exaggerated by distance, total number and spatial layout.

Examples include the following:

- In the traditional low-density residential layout, multiple individual narrow-diameter pipelines must be laid to service single homes that connect to a central collector line. This is more expensive than laying one large-diameter pipe that collects directly from houses laid out in clusters.

- If new development is focused around areas with existing service and utility infrastructure, the marginal costs to local governments are expected to be lower than the costs of new suburban development located beyond existing grids.

- The cost to run road maintenance programs and trash vehicles over greater distances is higher in low-density suburbs than in compact layouts and close-in locations.

- Energy costs for the individual consumer and for highway-related maintenance are higher in far-lying locations.

According to Eben Fodor (author of Better not Bigger), “Compact, well-planned growth consumes about 45 percent less land and costs 25 percent less for roads, 20 percent less for utilities, and 5 percent less for schools.”

Economic costs are also associated with lost agricultural lands and agricultural products because of encroachment on high-quality agricultural lands that border existing urban centers. (See Development at the Urban Fringe and Beyond: Impacts on Agriculture and Rural Land ![]() .)

.)

![[logo] US EPA](https://www.epa.gov/epafiles/images/logo_epaseal.gif)