Grantee Research Project Results

Final Report: Constructing Probability Surfaces of Ecological Changes in Coastal Aquatic Systems Through Retrospective Analysis of Phragmites Australis Invasion and Expansion

EPA Grant Number: R832440Title: Constructing Probability Surfaces of Ecological Changes in Coastal Aquatic Systems Through Retrospective Analysis of Phragmites Australis Invasion and Expansion

Investigators: Wardrop, Denice Heller , Whigham, Dennis F. , Patil, G. P. , Taillie, C. , King, Ryan , Easterling, Mary M.

Institution: Pennsylvania State University , Smithsonian Environmental Research Center , Virginia Institute of Marine Science

EPA Project Officer: Packard, Benjamin H

Project Period: July 1, 2005 through June 30, 2007

Project Amount: $299,995

RFA: Exploratory Research: Understanding Ecological Thresholds In Aquatic Systems Through Retrospective Analysis (2004) RFA Text | Recipients Lists

Research Category: Aquatic Ecosystems , Water

Objective:

- Choose an aquatic ecosystem with clearly identifiable alternative states, and define a limited number of variables that are considered to be the driving factors in state changes.

- Establish the database of explanatory and response variables over both a spatial and temporal extent. A retrospective analysis is the most powerful if performed over a truly temporal extent, instead of a space for time experimental design.

- Construct a probability surface of state change over the n-dimensional space of selected explanatory variables.

- Describe thresholds in terms of the probability surface.

- Test the threshold surface with data from a second location.

- Model the potential for state change under three proposed futures scenarios for the system of interest.

Summary/Accomplishments (Outputs/Outcomes):

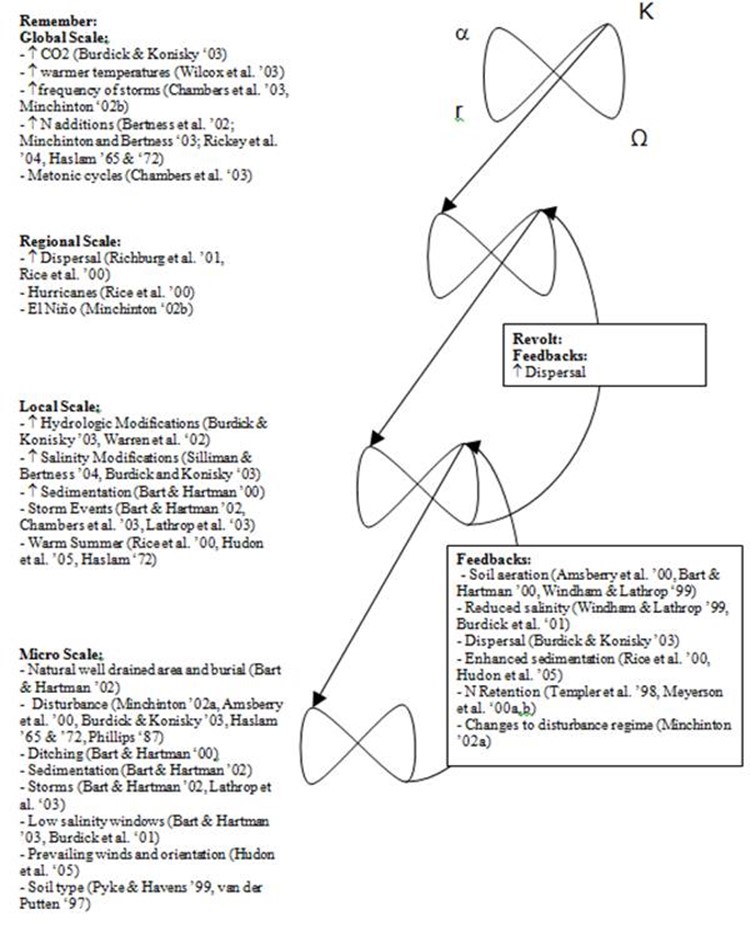

Conceptual Model Development and Variable Selection

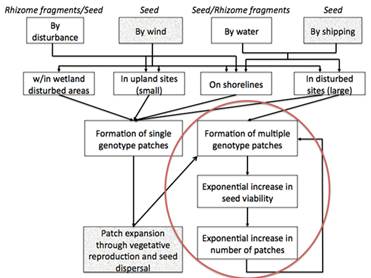

Figure 2. Conceptual model of significant variables in Phragmites invasion.

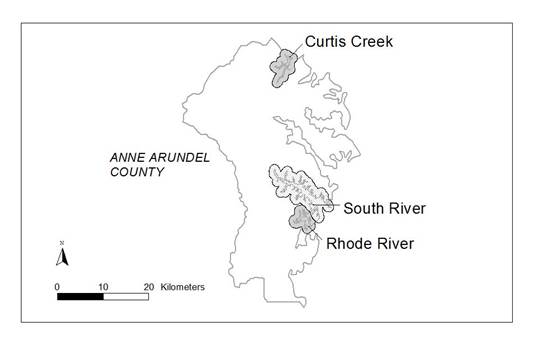

Documenting Historical Changes in Potential Driving Variables

Availability of Historical Data

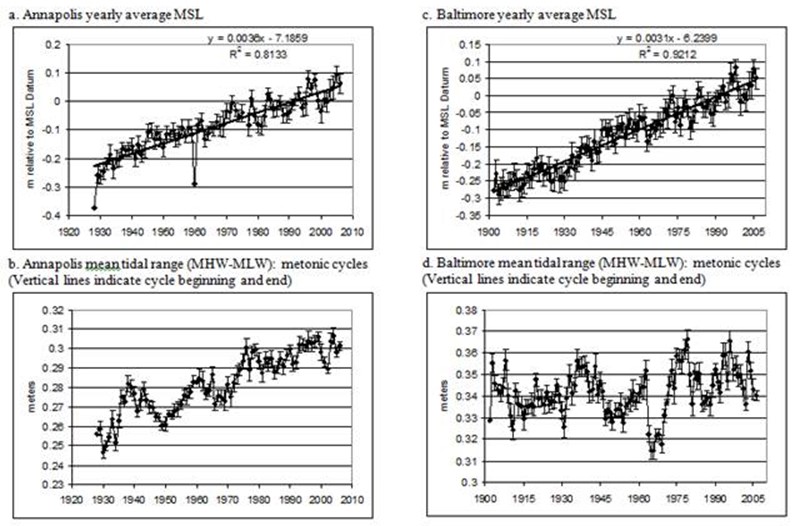

Historical Patterns of Potential Driving Variables

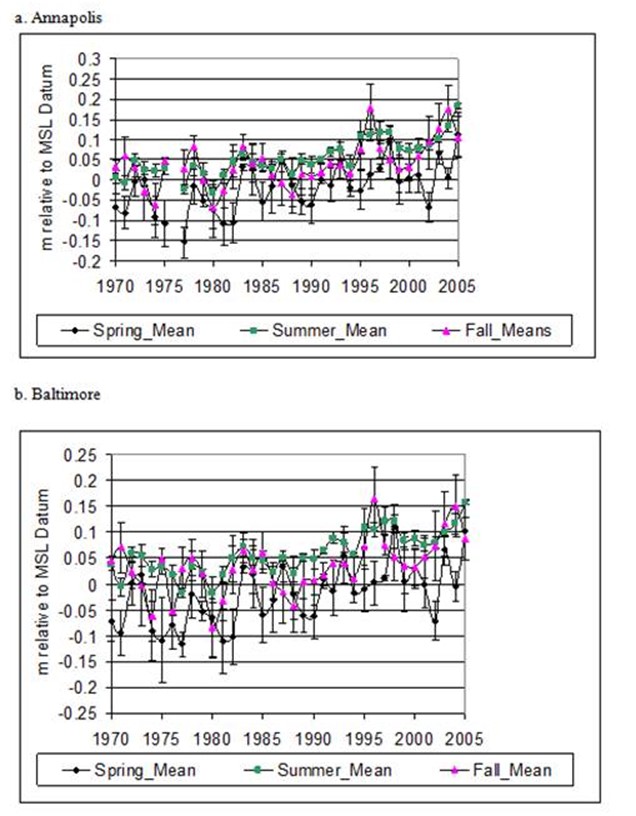

Figure 3. Yearly average water level data with standard error bars for Annapolis and Baltimore.

Figure 4. Sesonal water level means by year with standard error bars for Annapolis (top) and Baltimore (bottom).

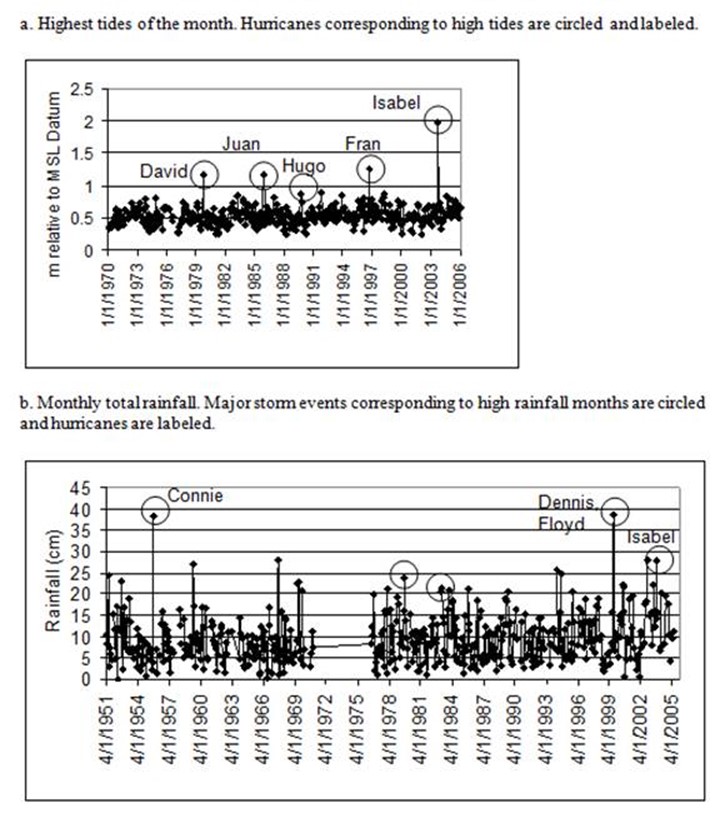

Figure 5. Annapolis tital and precipitation data used to determine extreme weather events.

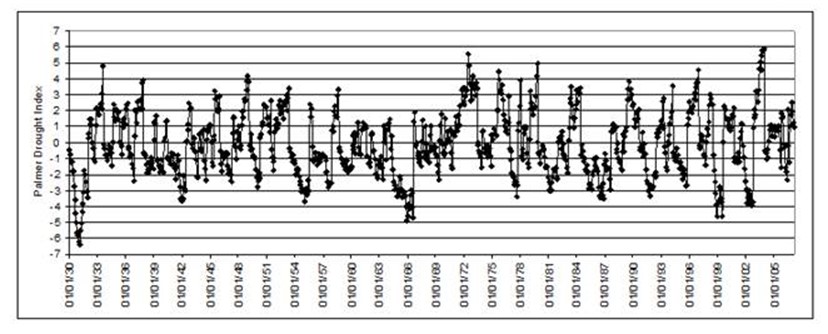

Figure 6. Maryland monthly Palmer Drought Severity Index scores, 1930-2007. Negative numbers indicate dry spells; positive numbers indicate

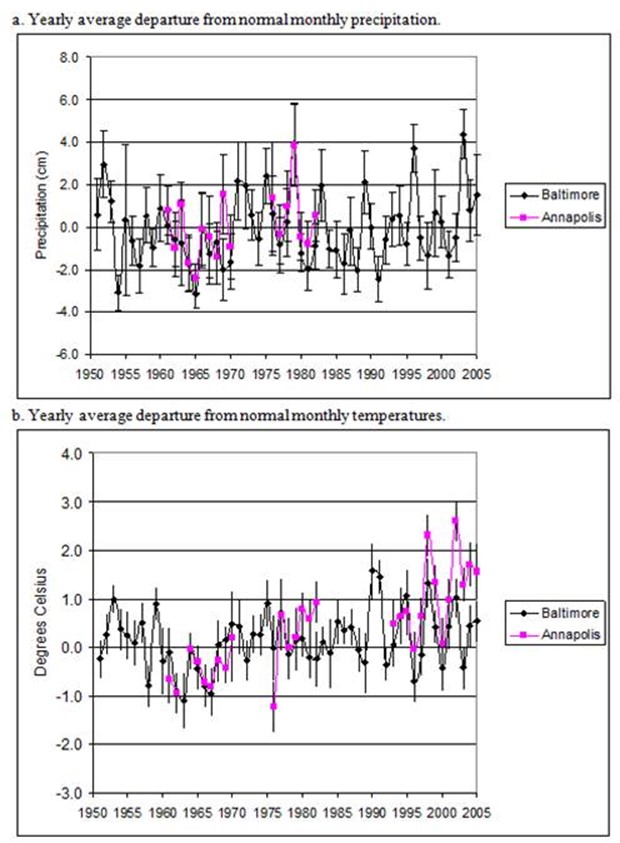

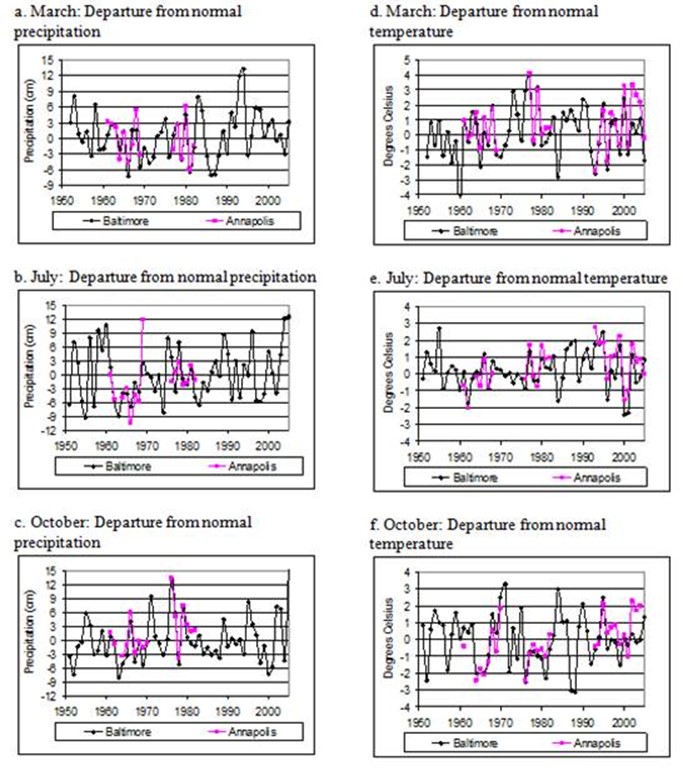

Figure 7. Yearly averages with standard error bars of monthly departures from normal precipitation and

temperature for Annapolis and Baltimore.

Figure 8. Annapolis adn Baltimore departures from normal precipitation in March (a), July (b), and October (c)

and temperature in March (d), July (e), and October (f).

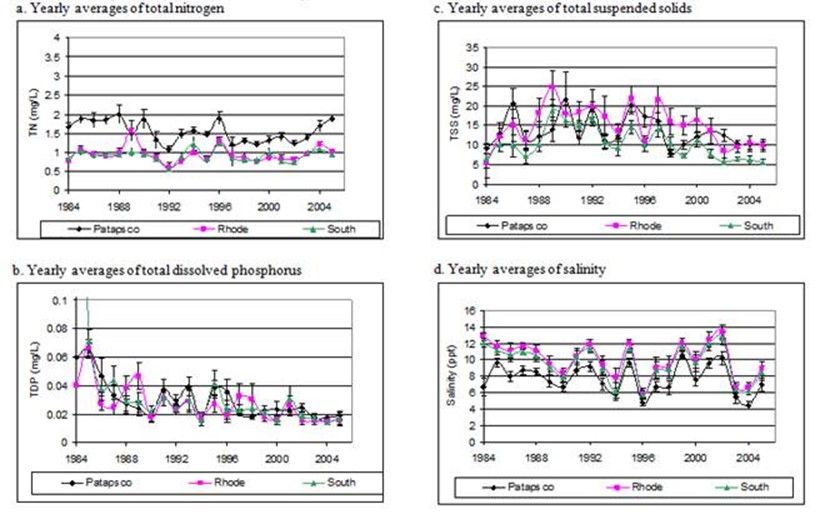

Figure 9. Yearly averages with standard error bars of montly samples of total nitrogen, dissolved phosphorous, total suspended solids and

salinity in the Rhode, South, and Patapsco Rivers.

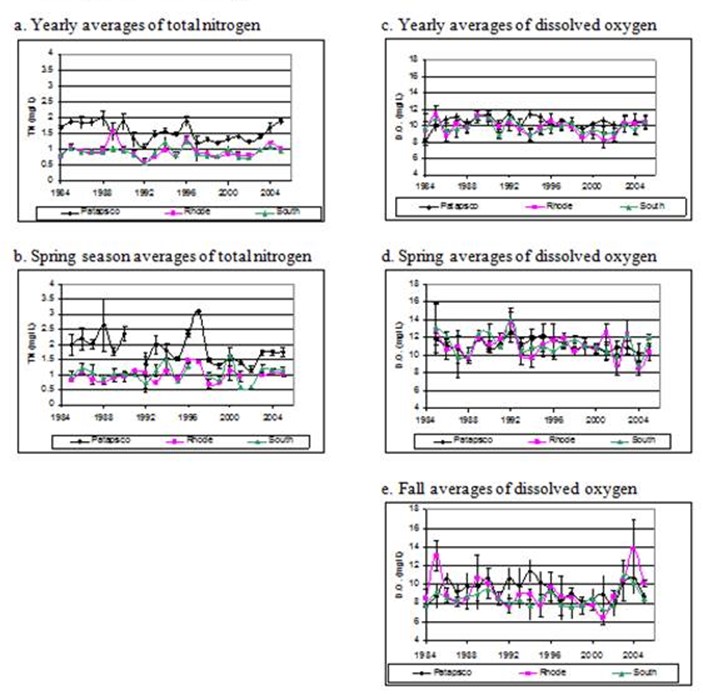

Figure 10. Comparisons of poorly corre3lated yearly averages and yearly seasosnal averages of total nitrogen and dissolved

oxygen.

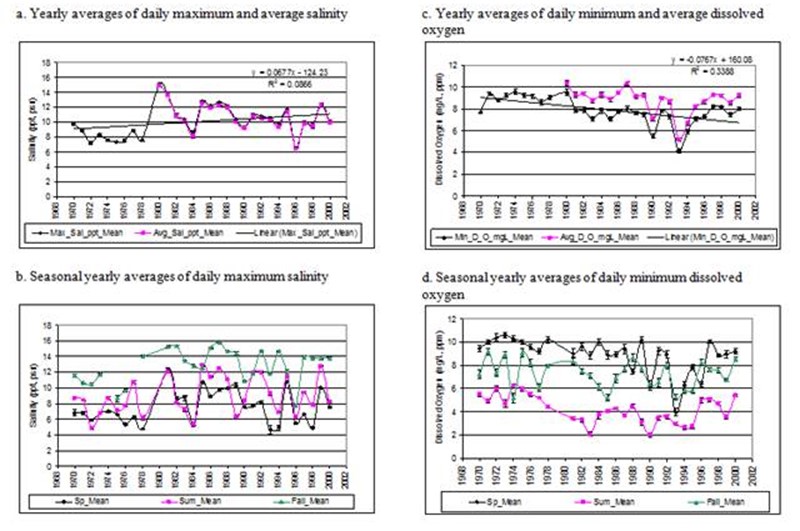

Figure 11. Salinity and dissolved oxygen data collected by SERC at a monitoring station on the Rhode River.

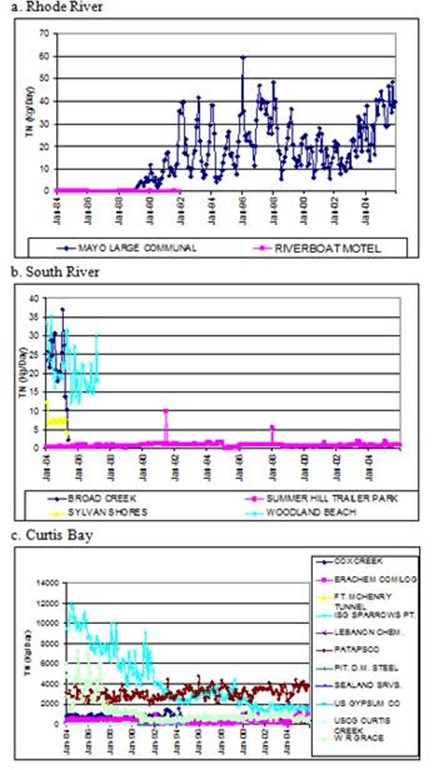

Figure 12. Discharge loads of total nitrogen from point sources in each

subestuary. Note differences in y-axis scales.

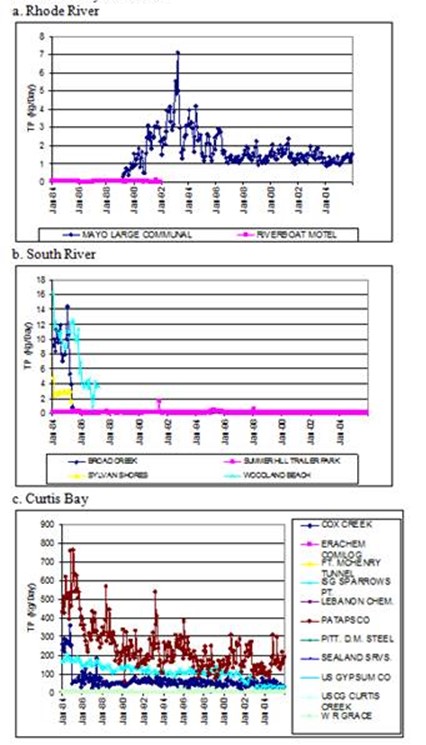

Figure 13. Discharge loads of total phosphorous from point sources

in each subestuary. Note differences in y-axis scales.

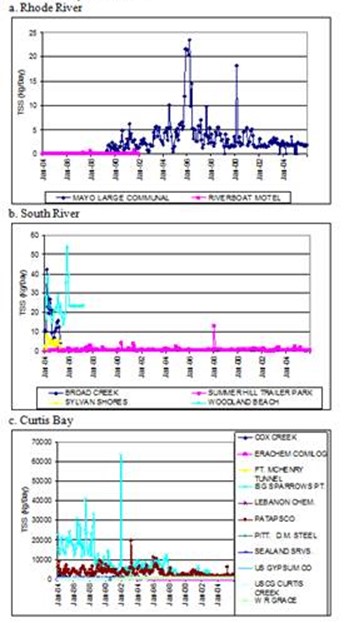

Figure 14. Discharge loads of total suspended solids from

point sources in each subestuary. Note differences in y-scale axis.

Reconstructing Historical Land Cover, Road Networks, and Shoreline Structures

| Year | Rhode River | South River | Curtus Bay |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1943 | N/A | Incomplete | Complete |

| 1952 | Incomplete | Incomplete | Complete |

| 1957 | Complete | Complete | Complete |

| 1962/3 | Complete | Complete | Incomplete |

| 1970 | Complete | Complete | Incomplete |

| 1977 | Complete | Incomplete | Complete |

| 1980 | Inomplete | Incomplete | Incomplete |

| 1984 | Complete | Complete | Complete |

| 1988 | Incomplete | Incomplete | Incomplete |

| 1990 | Complete | Complete | Complete |

| 1995 | Complete | Complete | Complete |

| 1998 | Complete (digital) | Complete (digital) | Complete (digital) |

| 2000 | Complete (digital) | Complete (digital) | Complete (digital) |

| 2002 | Complete (digital) | Complete (digital) | Complete (digital) |

| 2005 | Complete (digital) | Complete (digital) | Complete (digital) |

Each digital raster image was georeferenced to describe the specific geographic location of the image. Mapping software (ESRI ArcGIS 9.2) was used to complete the georeferencing. A base layer of current aerial imagery was used to compare the location of the scanned aerial image to a layer that already had geographic location information. Control points were added (usually fourone in each general corner region of the scanned image), matching road intersections or buildings. The scanned image was then transformed or warped to match the base image and this warping information was permanently saved with the scanned image. This transformation generally includes some discrepancy in matching to the base layer and so produces a residual error. The root mean square error (RMS error) was calculated to total the error for all of the control points related to the transformation of one image. The RMS error calculated for the images georeferenced for this project ranged from 2.02 to 17.04 with and average RMS error of 7.12.

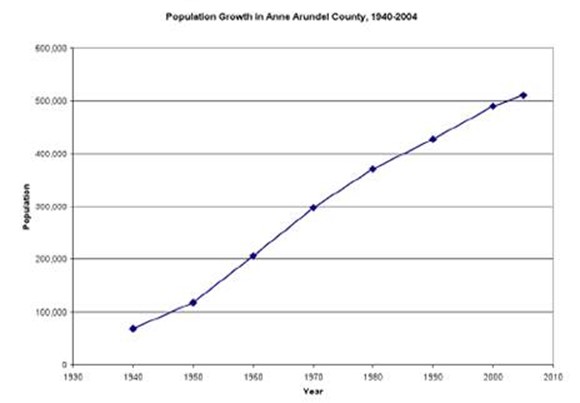

Figure 15. Population growth in Anne Arundel County.

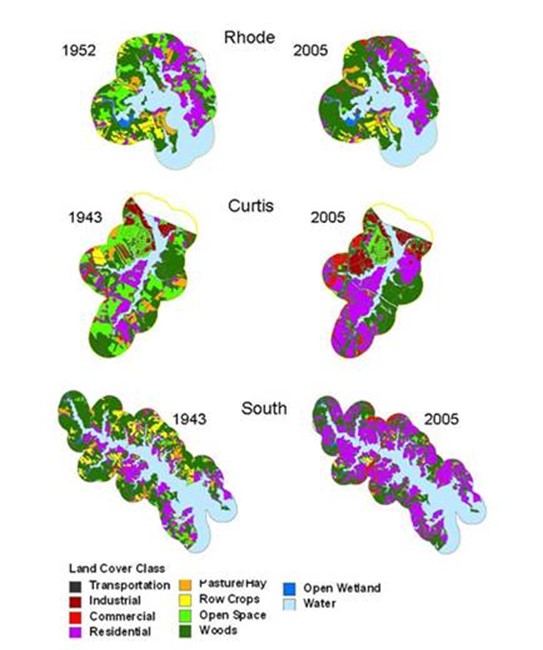

Figure 16. Land cover in 1943/1952 and 2005 in the three subestuaries of Anne Arundel Co., Md.

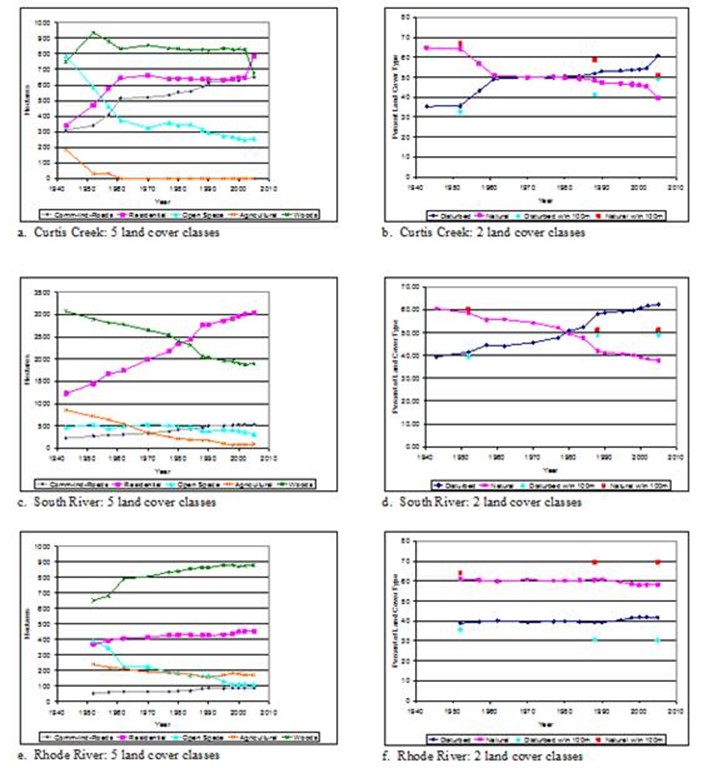

Figure 17 a-f. Changes in landcover over time in three subestuaries of Anne Arundel County, MD. Also shown in figures

b, d, and f is the percentages of disturbed vs natural landcover in a 100-m buffer around the wetlands of each.

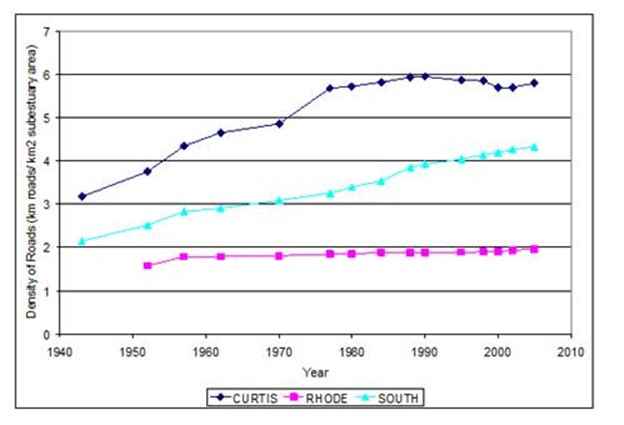

Figure 18. Change in road density from 1943 to 2005 in three subestuaries of Anne Arundel Co. MD.

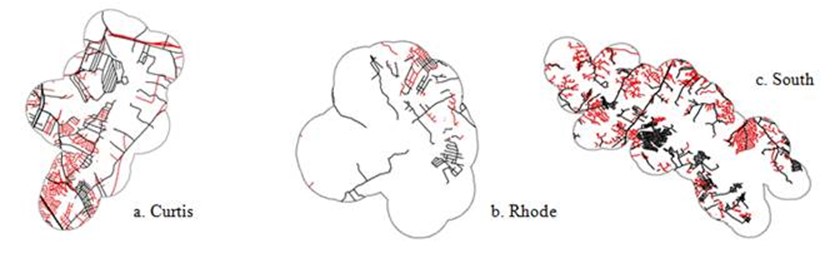

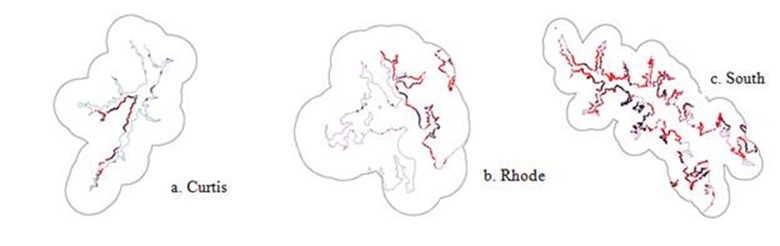

Figure 19. Road networks in three subestuaries of Anne Arundel Co. MD. Roads shown in black were presentt in 1943 (1952 for Rhode); roads shown in red

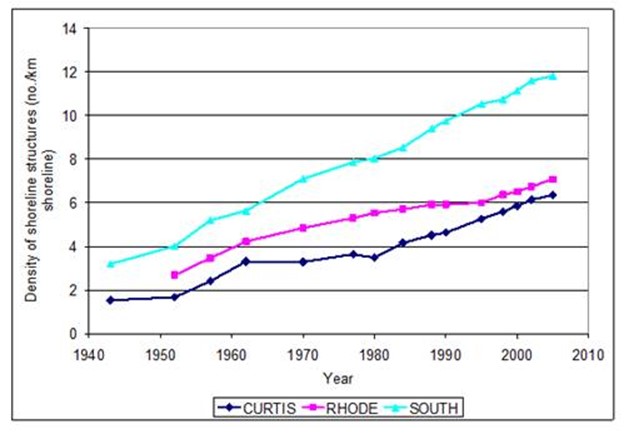

Figure 20. Change in the density of shoreline structures from 1943 to 2005 in three subestuaries of

Anne Arundel Co. MD.

Figure 21. Shoreline structures in three subestuaries of Anne Arunde Co. MD. Structures shown in black were present in 1943 (1952 for Rhode);

| Curtis | Rhode | South | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number in 2005 | Increase since 1952 | Number in 2005 | Increase since 1952 | Number in 2005 | Increase since 1952 | |

| Boat house | 13 | 550% | 19 | 217% | 93 | 127% |

| Dock | 201 | 319% | 265 | 168% | 1451 | 202% |

| Outfall | 0 | 2 | 100% | 21 | 250% | |

| Private ramp | 16 | 78% | 12 | 50% | 61 | 144% |

| Public ramp | 2 | 0% | 0 | 0 | ||

| TOTAL | 232 | 280% | 298 | 161% | 1626 | 195% |

Documenting Temporal Changes in Phragmites

1970s Tidal Marsh Survey

| Subestuary Name | Mapped Wetland Area 1975 (m2) | No. Phrag Patches 1975 | Phrag Area 1975 (m2) | Percent Phrag 1975 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Curtis | 108,286 | 2 | 2,633 | 2.4% |

| Rhode | 750,664 | 6 | 8,103 | 1.1% |

| South | 1,132,174 | 11 | 24,739 | 2.2% |

| Total | 1,991,124 | 19 | 35,475 | 1.8% |

SERC Aerial Photo Analysis

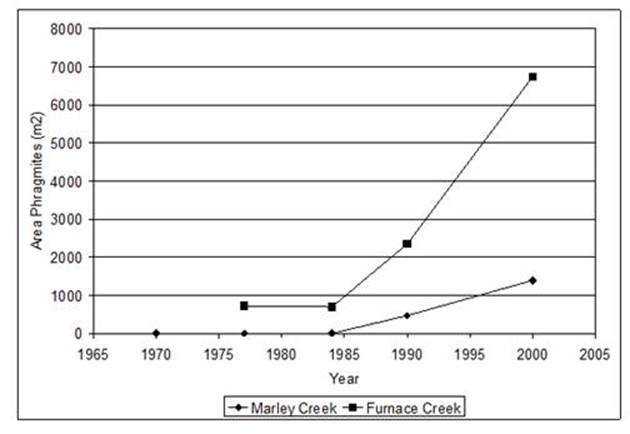

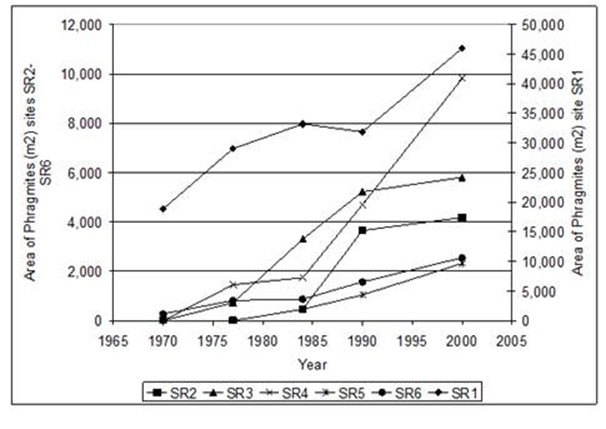

Figure 22. Changes in the area of Phragmites from 1970 to 2003 at two sites in the Curtis Creek subestuary

in Anne Arundel Co. MD.

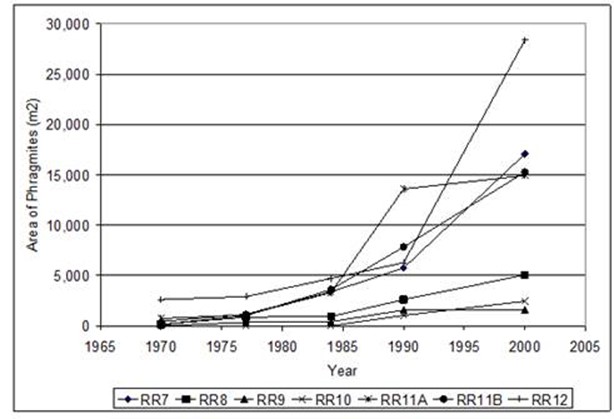

Figure 23. Changes in the area of Phragmites from 1970 to 2003 at seven sites in the Rhode RIver subestuary

in Anne Arundel Co., MD.

Figure 24. Changes in the area of Phragmites from 1970 - 2003 at six sites in the Suth River subestuary

VIMS Shoreline Survey

2007 Field Mapping

Aerial Photo Interpretation

Composite Presence/ Absence Assessment

Development of Spatial Datasets on Potential Driving Factors

| Curtis | Rhode | South | All | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wetland Attributes: | ||||||

| Number of Wetlands | 43 | 35 | 72 | 150 | ||

| Total Wetland Area (m2) | 136,470 | 328,034 | 954,048 | 1,418,552 | ||

| Avg. Perim-Area Ratio | 0.157 | 0.089 | 0.090 | 0.109 | ||

| Avg. Elevation (m) | 0.333 | 0.344 | .446 | 0.390 | ||

| Avg. Soil Organic Matter (%) | 92 | 28.8 | 33.2 | 25.3 | ||

| Avg. Dist to Nearest Wetl. (m) | 171.4 | 158.9 | 209.0 | 186.5 | ||

| Avg. Wetland Area (m2) | 3,174 | 9,372 | 13,251 | 9,457 | ||

| Phrag-related Attributes: | ||||||

| Avg. % Phrag 1976 | 0.92 | .14 | 2.57 | 1.53 | ||

| Avg. Dist. Phrag 1976 (m) | 1,803 | 1,212 | 1,702 | 1,617 | ||

| N. of Wetl. w/Phrag Present 5005 | 34 | 19 | 46 | 99 | ||

| % of Wetlands w/Phrag 2005 | 79.1% | 54.3% | 63.9% | 66.0% | ||

| Avg. % PHrag, all wetl. 2007 | 26.3 | 10.3 | ||||

| Avg. % Pgrag, wetl. w/Phrag 2007 | 36.5 | 20.1 | ||||

| 2005 Attributes for 100m Buffer around Wetland: | ||||||

| Avg. Density SS | 9.7 | 11.1 | 47.5 | 28.2 | ||

| Avg. Density Roads | 2,724 | 475 | 2,280 | 1,986 | ||

| Avg. % Developed | 25.5 | 8.6 | 31.5 | 24.4 | ||

| Avg. % Ag | 7.1 | 9.7 | 1.6 | 5.1 | ||

| Avg. % Forest | 32.3 | 41.0 | 27.4 | 32.0 | ||

| Avg. % Wetl | 1.1 | 0.9 | 7.3 | 4.0 | ||

| Avg. % Water | 34.3 | 39.8 | 32.2 | 34.6 | ||

| Other 2005 Attributes: | ||||||

| Avg. Dist to Nearest Shoreline Structure 2005 | 257.7 | 508.2 | 89.6 | 235.5 | ||

| 2005 Watershed Attributes: | ||||||

| % High Intensity Developed | 24.2 | 2.9 | 6.2 | |||

| % Low Intensity Developed | 29.2 | 16.6 | 34.9 | |||

| % High Intensity Ag | 0.0 | 4.3 | 0.7 | |||