Grantee Research Project Results

Final Report: Quantification and Modeling of Perchlorate Impacts from Fireworks on Drinking Water Sources

EPA Grant Number: R840554Title: Quantification and Modeling of Perchlorate Impacts from Fireworks on Drinking Water Sources

Investigators:

Institution:

EPA Project Officer:

Project Period: May 1, 2023 through May 2, 2025

Project Amount: $2,499,579

RFA: Assessing Perchlorate Occurrence in Ambient Waters Following the Usage of Fireworks Request for Applications (RFA) (2022) RFA Text | Recipients Lists

Research Category: Endocrine Disruptors , Drinking Water , Water Quality

Objective:

In the U.S, hundreds of millions of pounds of fireworks are ignited each year. Previous studies have shown that perchlorate (ClO4-) is a major ingredient in fireworks. Perchlorate is a drinking water concern due to its potential health effects based on its inhibition of iodide uptake by the thyroid and subsequent impacts on thyroid hormone production. After fireworks use, residual non-combusted ClO4- (as aerosols or particulates) is deposited onto the ground or water surface. Some studies have documented increased ClO4- concentrations in both surface and ground waters near major fireworks displays. However, there is only limited data on the relationship between firework use and its impact on drinking water sources due to increased ClO4- concentrations.

We proposed to evaluate the following hypotheses regarding the impact of fireworks on drinking water sources: 1) Fireworks would have a variable impact on surface water dependent on the mass of fireworks used, the dilution potential (rate and magnitude) of the water source, and the rate of biological perchlorate attenuation; 2) Impact would also depend on the magnitude of both direct deposition onto the water surface and the magnitude of subsequent inputs due to runoff or infiltration; 3) ClO4- concentrations in drinking water sources could be predicted based on fireworks consumption, hydraulic and ecological properties of the drinking water source, and hydrology of the region.

The proposed hypotheses were to be evaluated through 1) field studies (5 sites across the US) of the temporal evolution of ClO4- concentrations and isotopic composition in diverse (climate, surface water type) surface drinking water sources and groundwater drinking sources before and after centralized fireworks displays (e.g. 4th of July) in areas with and without public dispersed use of fireworks; 2) evaluations of aerial deposition at study sites and nationally, 3) nation-wide surveys of PWS intakes before and after periods of fireworks, and 4) watershed modeling combined with acquisition of population distribution and fireworks usage data.

The research would have resulted in a robust data set and expanded models that would have directly addressed ClO4- concentrations in drinking water supplies due to fireworks usage. The survey results would have allowed direct assessment of the impact of fireworks on drinking water sources. The research would also have produced a predictive screening model to evaluate impact based on site specific hydraulic, hydrologic, and ecological conditions as well as fireworks use. However, on May 9th 2025, in the beginning of the third year of the 4 year project, we were informed the research focused on drinking water safety had been terminated, due to it not meeting EPA priorities. As such, much of the work that was planned was not completed or some tasks were not even started. The research that was conducted is summarized below. Overall, our preliminary results suggested that fireworks may increase ClO4- concentrations in drinking water above those targeted for regulation in some cases. Due to the grant cancellation, the overall risk cannot be adequately evaluated. In addition, the tools that were meant to allow drinking water systems to predict relative risk will not be available.

Summary/Accomplishments (Outputs/Outcomes):

Summary of Results up to Grant Cancellation

Objective 1. Determine the relative impacts of fireworks use on ClO4- by direct deposition and secondary contamination from dissolution and transport after precipitation events (runoff).

We evaluated two locations using wet and total deposition samplers as well as monitored lakes, and tributaries for concentrations of perchlorate following events and/or rain events. At a site in Louisiana (Cross Lake), we conducted multiple rounds of deposition surveys including prior to fireworks sales, once fireworks sales commenced, before, during and after the 4th, as well as the period after the 4th when fireworks sales ceased. We collected dry and total deposition at locations throughout the city of Shreveport and at background locations. Extensive collection was done around the firework event on the lake itself. We also collected water samples in the lake which served as the drinking water supply for the city. Tributaries were sampled on a similar schedule. Results suggest widespread impact from both public and event-based use of fireworks. Deposition significantly increased in both wet and dry deposition. Perchlorate concentrations in deposition increased by two orders of magnitude during the 4th of July compared to pre-event deposition. Lake and tributary perchlorate concentrations increased in response to deposition. Average perchlorate concentrations in the lake which serves as a drinking water source for the city, increased by ~20 fold from event and public use of fireworks. Maximum lake concentrations (15 µg/L) exceeded previously proposed regulatory concentrations and similar concentrations were measured in surface runoff from the city. At the site in Georgia, similar efforts were made and maximum measured concentrations were even higher (15 µg/L) in surface tributaries.

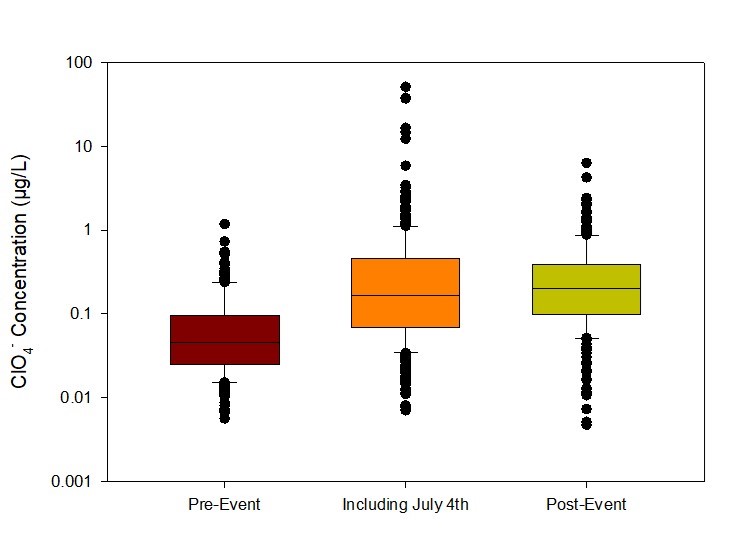

In year 2, we also evaluated lakes across the U.S. by collaborating with volunteers of the the North American Lake Management Society (NALMS - https://www.nalms.org/) . We received samples from ~ 300 lake volunteers (Figure 1) , who took samples before, immediately after the 4th, and one week after the 4th. Results indicate an order of magnitude increase in ClO4- concentrations after the 4th of July (Figure 1). Further, average ClO4- concentrations did not decrease after 1 week post fireworks display. In addition, at a number of lakes perchlorate concentrations exceeded existing or previously proposed regulatory limits. We were scheduled to receive a second round of more detailed samples from these lakes in the summer of 2025, however this was not possible after EPA determined that the research, focused on drinking water impacts, was no longer a priority.

Figure 1. Location of Lakes in the US where samples for perchlorate before and after fireworks were collected by volunteers.

Figure 1a. Total deposition before (background), during, and post 4th of July (period of maximum fireworks use) in year 1 for the Louisiana study site.

Objective 2. Evaluate the aerial deposition of ClO4- from centralized and dispersed displays.

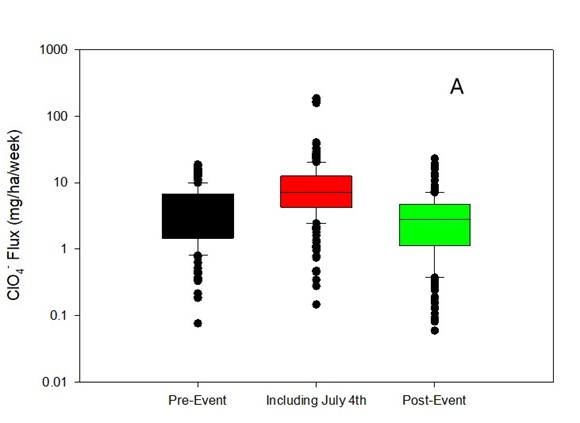

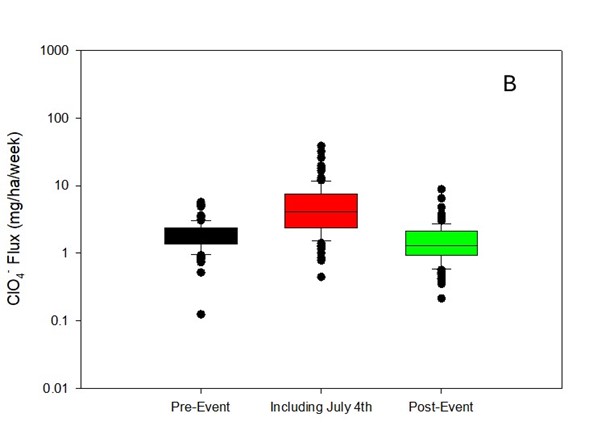

We acquired and analyzed wet deposition samples supplied by the National Atmospheric Deposition Program from locations representing 32 states over a 5-year period, with each location providing a sample prior to the week of the 4th, the week of the 4th and a week after the 4th. These sites represent both locations where public fireworks sales are allowed or are illegal, as well as rural and urban settings. We received and analyzed similar samples from the CASTNET program that monitors dry deposition for 28 sites and for two years. There was a significant increase in ClO4- deposition for the week of the 4th of July compared to the period prior and after the week of the 4th (Figure 2). Overall, average wet and dry deposition rates across the entire US increased by 300% during the 4th of July week, presumably due to fireworks use. Urban areas were more impacted than remote. The detailed analysis of this data set was ongoing when the grant was terminated. Research had been planned to use these deposition rates to model surface water concentrations, but this was not accomplished due to the grant being terminated.

Figure 2. A) Wet deposition for 75 NADP sites across 32 states over a 5 year period and B) Dry deposition for 28 CASTNET sites for two years including three time periods, before (background), during, and post 4th of July (period of maximum fireworks use).

Objective 3 Determine the mass of residual ClO4- produced from centralized and public fireworks use as a function of mass detonated and population density combined with fireworks sales, respectively.

Data on population was collected and used to evaluate mass deposition as a function of fireworks use. Preliminary data showed that there was a clear increase in perchlorate deposition in populated areas compared to background areas. These data were originally planned to inform a surface water quality predictive model but this work was not able to be completed due the grant being terminated.

The impact of fireworks due to both unused and discarded fireworks and residual ClO4- in expended fireworks was also evaluated. These sources would contribute to surface water concentrations, as during rain events the ClO4- would be dissolved and mobilized and end up in surface water or groundwater sources. Concentrations of perchlorate in unused fireworks ranged from 0.2 to 2.4% by mass. To put it in perspective, based on the average ClO4- content, one typical 10 gram firework would be able to increase 4,000 gallons of water above typical regulatory proposed limits. We also tried to evaluate the residual ClO4- in expended fireworks, as these are often not collected by the public. While we obtained the samples, analysis was not completed due to the EPA cancelling the grant.

Objective 4 Determine the biological attenuation rate as a function of surface water source depth, NO3- concentrations, and biogeochemical conditions of source water and sediment.

At both the Louisiana and Georgia sites, sediment samples were obtained to evaluate the degradation rates of perchlorate. Perchlorate degradation rates in sediment were rapid at both sites. The impact of NO3- and geochemical conditions was scheduled for testing in July of 2025, but these data are not available, due to grant cancellation.

Objective 5. Determine the potential for groundwater contamination.

Groundwater wells (5) were installed at a site in Delaware to evaluate the impact of a long-term centralized fireworks display. Testing of the wells was scheduled for July of 2025 prior to grant cancellation. Testing of existing wells indicated the presence of ClO4- near historic fireworks display area, which exceeded proposed safe drinking water concentrations but as the newly installed wells could not be sampled due to the grant cancellation the source is unclear.

Objective 6. Develop and validate (using data from objectives 1-4) watershed/ lake models to predict spatially varying ClO4- concentrations over time after fireworks use.

This objective was scheduled to commence in Year 3 prior to grant cancellation.

Objective 7. Develop a screening tool to estimate the relative risk of ClO4- contamination to drinking water sources from fireworks usage.

This objective was scheduled to commence in Year 4 prior to grant cancellation.

Conclusions:

Due to the EPA deciding that our grant, focused on drinking water quality and drinking water safety, was no longer a priority, much of the grant activities were not completed or even started. Further, as no notice of the cancellation was given, we were not able to complete the analysis or presentation of the results collected. The data collected and analyzed prior to the cancellation strongly suggested that fireworks do impact drinking water sources across the US and that their use leads to elevated surface and groundwater concentrations as well as increased deposition. Unfortunately, the modeling task was not able to be performed, which would have allowed the impact to be directly addressed. Further, a tool that could have been used by public water systems to estimate risk was also unable to be completed, which not only prevents drinking water safety from being evaluated but also could lead to higher public treatment costs. Multiple publications will eventually come from the collected data, but have not been produced, due to the abrupt grant cancelation with no notice.

Supplemental Keywords:

Endocrine Disruptors, Drinking Water, Water QualityProgress and Final Reports:

Original AbstractThe perspectives, information and conclusions conveyed in research project abstracts, progress reports, final reports, journal abstracts and journal publications convey the viewpoints of the principal investigator and may not represent the views and policies of ORD and EPA. Conclusions drawn by the principal investigators have not been reviewed by the Agency.