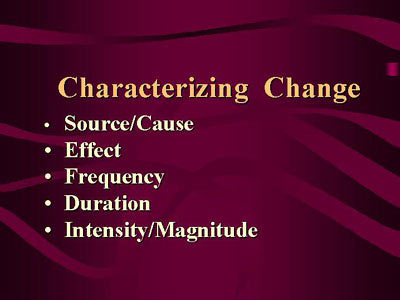

Characterizing Change

Different types of changes are usually described in terms of the sources or causes of change and the effects they bring about in the watershed ecosystem. In addition to the type of change that occurs, disturbance processes are typically characterized according to the frequency of occurrence, as well as the duration of their effects. In general, geological processes and climate cause the primary natural changes affecting higher levels of organization (i.e., the larger-scale watersheds) over long periods of time. Within the context of these larger-scale and long-term processes, ongoing frequent and smaller-scale processes also produce change.Change processes may also be characterized according to the intensity or magnitude of their effects. Intensity of disturbance is typically defined according to the magnitude of effects on biotic communities, but can imply physical effects as well (e.g., magnitude of a flood or the quantity of sediments it has moved).

Frequency and intensity of change can highly influence plant and animal communities; species associated with frequently disturbed habitats tend to develop adaptations that allow them to persist or even thrive under those conditions. For example, trees growing in low floodplains subjected to frequent flooding often produce adventitious roots that allow for oxygenation following burial by water and sediment. In dry, upland forests, species such as ponderosa pine withstand frequent fires through such adaptations as the development of thick, fire-resistant bark and dropping of lower limbs to minimize the spread of fire to the crown. Within many watersheds, upper reaches are often prone to infrequent, high-intensity events (e.g., landslides, debris flows), whereas lower reaches tend to be affected by frequent, low-intensity events (e.g. sediment transport and redeposition).

The frequency and intensity of such changes as flooding, windstorms, hurricanes, and brush fires also heavily influence land use planning decisions for many communities, who are often placed in a position of continually evaluating and managing risks versus potential benefits. Examples include southeastern US coastal communities' interactions with hurricanes, and the recurrent flood management decisions of many US towns located on river floodplains. Thorough understanding of all aspects of potential changes can help these communities make sound decisions.

Changes of Concern

Environmental changes almost always benefit some species to the detriment of others. Accordingly, environmental degradation is a subjective, value-laden concept influenced by different ideas of desired environmental conditions. Changes that markedly decrease populations of favored wildlife or plant species, or limit a watershed's ability to provide resources for human communities (e.g., potable water, food/fiber, aesthetics) are widely seen as degradation especially by affected people.

But, besides these human examples, other patterns of significant change are also symptomatic of degradation; these types of change are not necessarily related to human values or perceptions, but adversely affect ecosystems in ways beyond what is immediately useful to man. These changes include reduced efficiency of nutrient cycling, changes in productivity, reversed successional sequences, reduced species diversity, changes in size distribution of species, increased abundance of tolerant "generalist species" relative to "specialists", increased incidence of disease, and greater population fluctuations (Steedman and Regier 1987).

Changes that produce significant, widespread and/or long-term degradation are changes of concern. These types of changes alter the ways in which ecosystems organize, remain functional, and evolve over time, and threaten the abilities of ecological communities to recover and persist following periodic disturbance. Change of concern in the watershed may be defined as the significant alteration or loss of a primary watershed process or structural component that persists beyond normal cyclical change (e.g., seasonal change).

Changes of concern are most often related to a human-made cause or to the high-magnitude, cumulative effects of human-made plus natural agents acting together. Except for major evolutionary events discussed earlier, purely natural changes are often not permanently degrading to whole ecosystems because these ecosystems developed in adaptation to these very same changes. As human-made changes are very recent and often very intensive changes, they have not been easily accommodated by ecosystems and thus can lead to more significant and long-lasting degradation.

Nevertheless, it is also possible to consider any change as a change of concern if its "temporary" disruption is unacceptable on human time scales (e.g., duration in human rather than geologic terms) consider, for example, earthquakes at the San Andreas fault, or a forest fire near a residential community that treasures its nearby woods. Although many natural changes can reach magnitudes often called "natural disasters," still they represent changes from which watersheds can and do eventually recover, often with different ecological features than before. Human evaluation of the seriousness of natural disasters relates closely to the time scales necessary for recovery of the ecosystem components valued by people.

It is very important to note that many human-made changes of concern are not unavoidable, and considerable progress has been made in understanding human influence on change and how to manage our impacts. Rather, one of the biggest problems is limited awareness of the necessary remedies and a related unwillingness to use them. A major challenge for the watershed manager is to recognize when a change or the risk of a future change represents a potentially damaging change of concern rather than a temporary, recoverable change that will leave ecological processes and valued attributes of the watershed intact and functional. When an environmental change proceeds past a certain threshold level, it often results in a change of state at which previous relationships within the ecosystem no longer hold.

Take a moment: Earlier you were asked to think about changes of all kinds in your own watershed. Do you now feel that any of these changes are changes of concern? To whom or what are they of particular concern? Is your judgment based on these changes causing losses of things valued by people, based on losses of key ecosystem features or functions, or based on both?

![[logo] US EPA](https://www.epa.gov/epafiles/images/logo_epaseal.gif)