Ambient Concentrations of Particulate Matter

- Introduction

“Particulate matter” (PM) is the general term used for a mixture of solid particles and liquid droplets found in the air. Airborne PM comes from many different sources. “Primary” particles are released directly into the atmosphere from sources such as cars, trucks, heavy equipment, forest fires, and other burning activities (e.g., burning waste, wood stoves, wood-fired boilers). Primary particles also consist of crustal material from sources such as unpaved roads, stone crushing, construction sites, and metallurgical operations. “Secondary” particles are formed in the air from reactions involving precursor chemicals such as sulfates (which are formed from sulfur dioxide emissions from power plants and industrial facilities), nitrates (which are formed from nitrogen dioxide emissions from cars, trucks, and power plants), and carbon-containing reactive organic gas emissions from cars, trucks, industrial facilities, forest fires, and biogenic sources such as trees (U.S. EPA, 2019).

Ambient air monitoring stations throughout the country measure air concentrations of PM, with most monitoring for two size ranges: PM2.5 and PM10. PM2.5 consists of “fine particles” with aerodynamic diameters less than or equal to 2.5 microns (μm). PM10 includes both fine particles (PM2.5) and “coarse particles,” with aerodynamic diameters greater than 2.5 μm and less than or equal to 10 μm. The chemical makeup of particles varies across the U.S. For example, fine particles in the eastern half of the U.S. contain more sulfates than those in the West, while fine particles in southern California contain more nitrates than those in other areas of the U.S. Carbon is a substantial component of fine particles everywhere (U.S. EPA, 2004, 2019).

Fine particles also have seasonal patterns. PM2.5 concentrations in the eastern half of the U.S. are typically higher in the third calendar quarter (July-September), when sulfates are more commonly formed from sulfur dioxide emissions from power plants in that part of the country. Fine particle concentrations tend to be higher in the fourth calendar quarter (October-December) in many areas of the West, in part because fine particle nitrates are more readily formed in cooler weather, and wood stove and fireplace use produces more carbon. Additionally, nitrate concentrations within particles are highest during the winter in the upper Midwest (U.S. EPA, 2019).

An extensive body of scientific evidence shows that short- or long-term exposures to fine particles can cause adverse cardiovascular effects, including heart attacks and strokes resulting in hospitalizations and, in some cases, premature death. A number of studies have also linked fine particle exposures to respiratory effects, including the exacerbation of asthma and other respiratory illnesses (short-term exposures) and the impairment of lung development (long-term exposures). More limited scientific evidence provides support for associations with a broader range of health effects (e.g., nervous system effects, cancer) and for health effects following exposures to PM size fractions other than fine particles (i.e., thoracic coarse particles, ultrafine particles) (U.S. EPA, 2019).

Specific groups within the general population are at increased risk for experiencing adverse health effects related to PM exposures including older adults, individuals with cardiopulmonary diseases such as asthma or heart disease, children, and people with lower socioeconomic status (U.S. EPA, 2019).

Unlike other criteria pollutants, PM is not a single specific chemical entity, but rather a mixture of particles from different sources with different chemical compositions. Efforts to evaluate the relationships between PM composition and health effects continue to evolve. While many constituents of PM have been linked with health effects, the available evidence does not allow the identification of particular components, groups of components, or sources that are more closely related to specific health outcomes. The available evidence also does not allow the exclusion of any individual component, group of components, or sources from the particle mixture of concern (U.S. EPA, 2019).

PM also can cause adverse impacts to the environment. PM-related welfare effects include visibility impairment, climate impacts, effects on materials (e.g., building surfaces), and ecological effects (U.S. EPA, 2019, 2020).

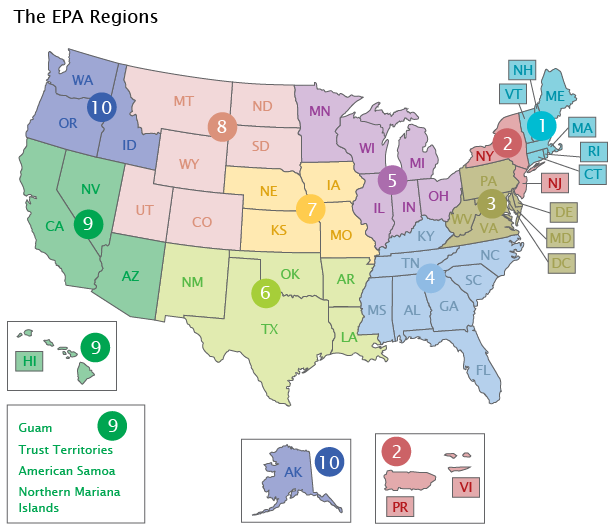

This indicator presents trends in PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations, using averaging times consistent with the pollutants’ corresponding National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS). For PM10, trend data from 1990 to 2021 are presented for the second highest 24-hour concentrations measured at the trend sites during each calendar year. For PM2.5, trend data from 2000 to 2021 are presented both for annual average concentrations and for the 98th percentiles of 24-hour average concentrations measured at the trend sites for each calendar year. Trend data are based on measurements from the State and Local Air Monitoring Stations network and from other special purpose monitors. This indicator presents PM10 trends for 90 monitoring sites in 59 counties nationwide and annual average PM2.5 trends for 375 monitoring sites in 292 counties nationwide. For both PM10 and PM2.5, the indicator displays trends for the entire nation and for the ten EPA Regions.

The indicator’s exhibits display the pollutants’ NAAQS as points of reference. However, the fact that the national values or those shown for EPA Regions fall below the standards does not mean that all monitoring sites nationally or in any particular EPA Region also are below the standards. The indicator displays trends in the number of PM10 monitoring sites and PM2.5 monitoring sites nationwide that recorded ambient air concentrations above the level of the standards, but these statistics are not displayed for each EPA Region.

- What the Data Show

PM10 Concentration Trends

In 2021, the national 24-hour PM10 concentration (based on the second highest 24-hour concentrations across all sites) was 32 percent lower than the average 1990 level (Exhibit 1). Additionally, of the 90 sites used to determine this trend (out of 615 total monitoring sites that were operating in 2021), the number reporting PM10 concentrations above the level of the 24-hour standard decreased from nine to three between 1990 and 2021 (Exhibit 2). Most EPA Regions experienced a decrease in 24-hour PM10 concentrations over this period; the main exception is elevated PM10 concentrations recorded in Region 10 in 2017 and 2020, likely due to air quality impacts from wildfires in the Pacific Northwest (Exhibit 3). EPA Region 2 showed the greatest relative decrease (65 percent) in PM10 concentrations since 1990.

Also shown in Exhibit 1 are the 90th and 10th percentiles based on the distribution of annual statistics at the monitoring sites. This provides additional graphical representation of the distribution of measured concentrations across the monitoring sites for a given year. Thus, the graphic displays the concentration range where 80 percent of measured values occurred for that year. (Note that this presentation style also applies to Exhibits 4 and 7, discussed below.)

PM2.5 Concentration Trends

Annual average PM2.5 concentrations decreased 37 percent between 2000 and 2021 (Exhibit 4). This trend is based on measurements collected at 375 monitoring sites that have sufficient data to assess trends over that period. The number of monitoring sites in this trend (375 out of 833 total sites that were operating in 2021) reporting ambient air concentrations above the level of the annual average PM2.5 standard decreased by 93 percent over this period (Exhibit 5). Regional declines were greatest in EPA Regions 2, 3, and 4, where the annual average PM2.5 concentration in 2021 was 45 percent lower than in 2000 (Exhibit 6).

In 2021, the average of 98th percentiles of 24-hour PM2.5 concentrations at the 375 monitoring sites used for the trend was 33 percent lower than the 2000 level (Exhibit 7). The number of monitoring sites in this trend (375 out of a total of 850 sites that were operating in 2021) reporting ambient air concentrations above the level of the 24-hour PM2.5 standard declined 79 percent over this period (Exhibit 8). Most EPA Regions experienced decreasing 24-hour PM2.5 concentrations between 2000 and 2021, with Region 3 showing the largest decline (46 percent) (Exhibit 9). The 98th percentile of 24-hour PM2.5 concentrations in Regions 8, 9, and 10 all increased in recent years; this increase mainly reflects air quality impacts from wildfires during this time frame.

- Limitations

- Because there are far more PM10 and PM2.5 monitors in urban areas than in rural areas, the trends might not accurately reflect conditions outside the immediate urban monitoring areas.

- PM10 and PM2.5 measurement data are based on monitoring methods that are consistent with those used to establish EPA’s National Ambient Air Quality Standards. These “indicator” measurements provide mass concentrations that may be different than the concentrations of particulate matter (PM10 and PM2.5) in the ambient air. These potential differences are due to losses from volatilization of nitrates and other semi-volatile materials and retention of particle-bound water associated with hygroscopic species. A study of six locations in the Eastern U.S. showed that the net difference was less than 10 percent (Frank, 2006).

- Due to the relatively small number of monitoring sites in some EPA Regions, the regional trends are subject to greater uncertainty than the national trends. Some EPA Regions with low average concentrations may include areas with high local concentrations, and vice versa. In addition, the trend sites in this indicator are not dispersed uniformly across all states in the EPA Regions. For instance, the 90 PM10 trend sites are located in 25 states. In the remaining 25 states, there currently are insufficient long-term data from the existing PM10 monitoring sites to include in this indicator. In contrast, the 375 annual average PM2.5 trend sites are located in 47 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. The remaining three states did not have sufficient long-term data from the existing PM2.5 sites to include in this indicator.

- To ensure that long-term trends are based on a consistent set of monitoring sites, selection criteria were applied to identify the subset of PM monitoring sites with sufficient data to assess trends over the time frames covered by this indicator. Monitoring sites without sufficient data are not included in the trend analysis. Some excluded monitoring sites reported PM concentrations above the level of the PM standard during the years covered by this indicator. In 2021, for example, 74 monitoring sites nationwide recorded 24-hour PM10 concentrations above the level of the NAAQS: this includes the three sites shown in Exhibit 2, and 71 sites that did not have sufficient long-term data to be included in this indicator.

- Data Sources

Summary data in this indicator were downloaded from EPA’s National Air Quality: Status and Trends of Key Air Pollutants website (U.S. EPA, 2022a) (https://www.epa.gov/air-trends). The trends data are based on PM ambient air monitoring data in EPA’s Air Quality System. National and regional trends in this indicator are based on the subset of PM monitoring stations that have sufficient data to assess trends over the period of record (i.e., since 1990 for PM10 and since 2000 for PM2.5).